On Thursday morning, the U.S. Department of Labor reported that weekly jobless benefits claims had fallen again. Both the absolute level -- 390,000 -- and the four-week-moving average -- 400,000 -- were the best numbers we've seen since April, supplying the latest confirmation that the U.S. economy is headed in the right direction, albeit very, very slowly.

Trade data reported on Thursday indicated the U.S. also sold a record amount of exports to the rest of the world in October -- proof that we are making things that the rest of the world wants to buy. That's good news for the U.S., and conceivably, for the White house. Even though at this point in the political cycle, it may already be too late to change voter perceptions of the economy, it certainly won't hurt Obama's prospects for reelection if the economic situation steadily improves over the next 12 months.

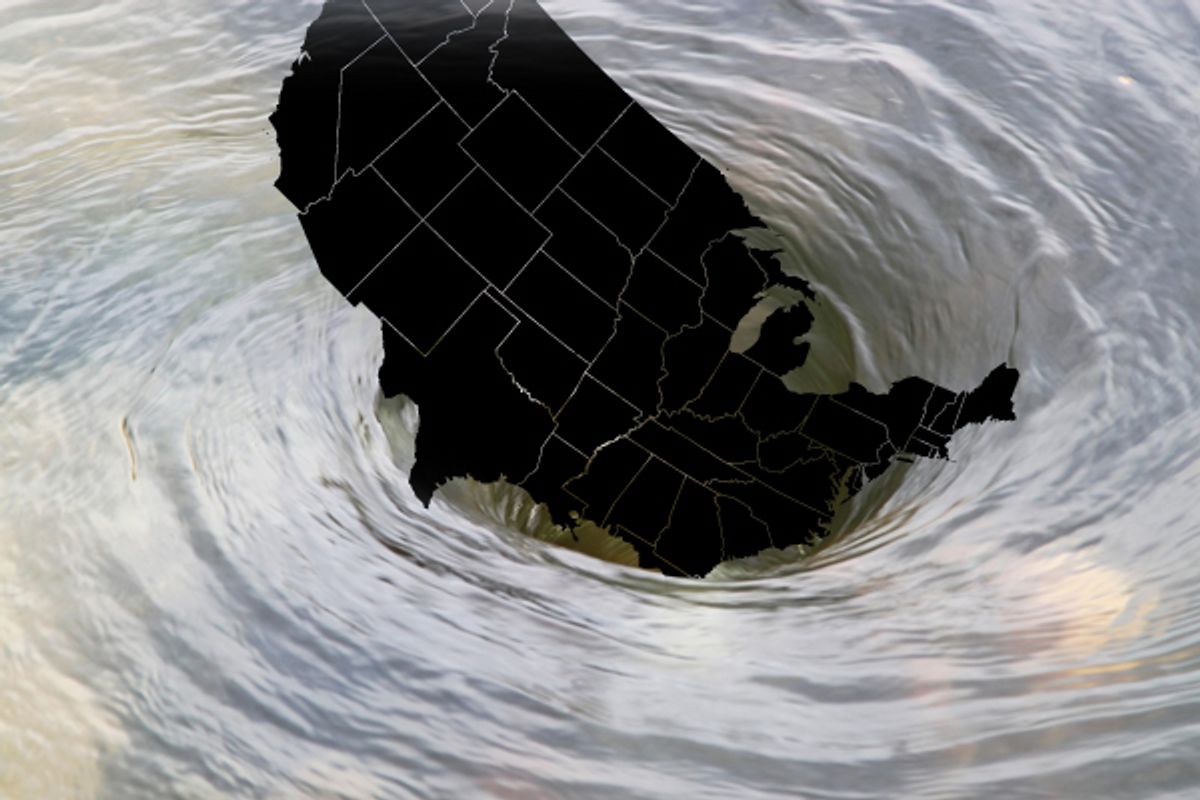

But in the context of the rolling train wreck that is the eurozone, neither the week-to-week health of the U.S. labor market nor a positive blip in trade data mean much at all. The best one can argue is that mildly good domestic economic news provides a shock absorber that helps smooth out the bumps coming from Europe. The worst-case scenario, on the other hand, is another global recession. Even the best shock absorber is useless when the locomotive goes right off the track.

For starters, it's difficult to envision a scenario in which a severe European recession does not have a negative effect on the U.S. economy. At the very least, U.S. exports would take a hit. Italy alone is the seventh- or eighth-largest economy in the world; destabilization there would ripple out everywhere. But even more troubling is what might happen if Italy's troubles spread to France and end up forcing the breakup of the European monetary union.

Gaming out the implications of the European financial crisis includes many imponderables. But the main explanation for why U.S. stock market investors are so skittish today is that the possibility of "a gigantic financial shockwave" sweeping through the world's banking system seems to get realer by the day. Call it the Return of the Credit Crunch Monster -- as European panic spreads globally, banks will stop lending to each other and everyone else, and the world economy will head back into a deep freeze.

Brad DeLong, an economic historian at the University of California at Berkeley, is sounding the alarm:

The time is 1931, and we are Austria.

The Federal Reserve needs to buy up every single European bond owned by every single American financial institution for cash before the increase in eurorisk leads American finance to tighten credit again and send us down into the double dip.

The Federal Reserve needs to do so now.

There's a theory that argues that because U.S. banks do not have a lot of direct exposure to European sovereign debt, the overall impact of the crisis will be limited. That line of thought appears to underestimate the depth and complexity of the interconnections that link the world's financial institutions. As Barry Eichengreen, an economist at U.C. Berkeley who has studied European monetary integration in great depth, notes, many big European banks do plenty of business in the United States. If they run into trouble at home, there will be follow-on effects in the U.S. But more to the point, if we learned anything from the previous credit crunch, it's that our understanding of how banks are exposed to each other is very limited. How many more MF Globals are out there, sitting on bad bets on European bonds or credit default swaps that are waiting to explode?

As the Washington Post's Ezra Klein reports:

As Desmond Lachman, a former IMF official, told me last week, "We may not have much direct exposure to the periphery, but we’ve got exposure to bets in Europe that have exposure to the periphery. And that means we've got exposure."

So will the Federal Reserve come to the rescue, as Brad DeLong hopes. If Ben Bernanke is so inclined, he's not going to get any political cover from the right. At Wednesday night's Republican presidential candidates' debate, the GOP's best and brightest presented a unanimous front: The U.S. should offer no help to Europe. Let them fix their own problems.

We could mutter foul imprecations against Republican isolationism and head-in-the-sand stupidity, but the truth is that even if the Federal Reserve did act to protect U.S. banks, there's still not a whole hell of a lot the U.S. can do that would make a meaningful difference to Europe's future. The scope of the problem is simply too big, and the political issues in play -- Germany's unwillingness to pay the costs of keeping the entire structure afloat -- are something U.S. politicians have no influence over. We can do little but watch and hope, even as we see the most pessimistic predictions made by Euro skeptics come true, day by day.

Shares