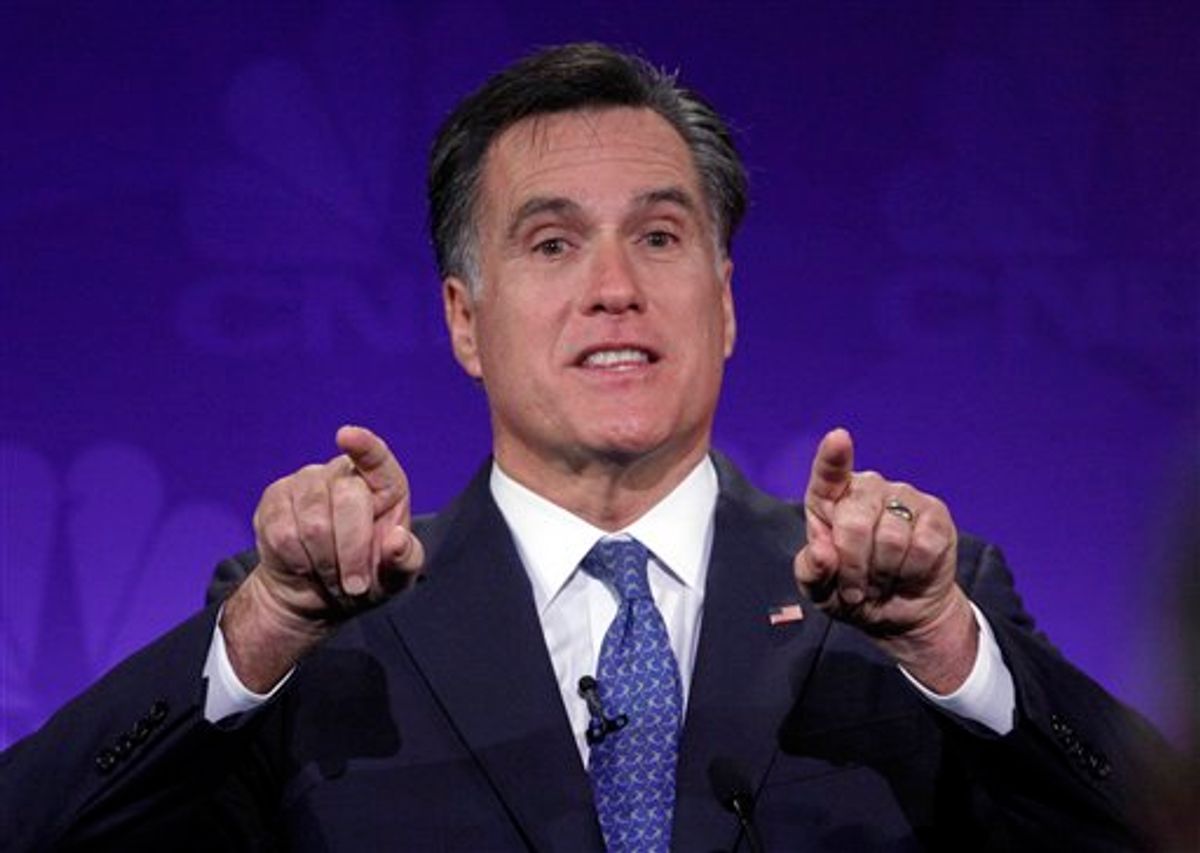

Once again, Mitt Romney met his Republican presidential rivals for a debate this weekend, and once again he sustained no apparent damage. It seemed like just the latest stop on the Romney Inevitability tour.

You know the idea: Rick Perry has self-destructed several times, Newt Gingrich is mainly interested in selling books and movies and will implode quickly if the press decides he's actually a contender, there's no way Republicans will let Herman Cain anywhere near their nomination, Michele Bachmann is too far out there for even Rush Limbaugh, and you can forget about Rick Santorum, Jon Huntsman and Ron Paul. Which pretty much leaves Romney as the last credible candidate standing. As NBC's First Read put it last week:

After Herman Cain’s defiant news conference on Tuesday and after Rick Perry’s brain freeze at Wednesday night’s CNBC debate, Mitt Romney’s path to the GOP presidential nomination is now WIDE open. In fact, not since Bob Dole in 1996 has a candidate been such a clear front-runner right before the primaries and caucuses begin.

As I wrote recently, a very plausible scenario does exist in which Romney wins Iowa and every caucus and primary contest that follows, becoming the first non-incumbent Republican in the modern era to run the table en route to the nomination. (This feat was achieved on the Democratic side by Al Gore in 2000.) But juxtapose the inevitability narrative against some of the Republican polling and things can feel a bit confusing. In one new survey, Romney leads the GOP pack, but with only 23 percent, and in another he's tied for second with a paltry 15 percent. This becomes all the more striking when you compare it to past "inevitable" GOP candidates.

For instance, First Read likens Romney to Dole in '96. But at this point in that cycle -- roughly seven weeks before Iowa -- a CBS News poll showed Dole leading the national GOP horse race with 45 percent, followed by Phil Gramm and Pat Buchanan at seven percent each and Steve Forbes at five. And Dole's margin was actually nothing compared to George W. Bush's in the 2000 cycle; back then, he enjoyed a 48-point lead over John McCain -- 60 to 12 percent -- seven weeks before Iowa, with Steve Forbes at five percent and Alan Keyes at three. There's also the case of George H.W. Bush in 1988; he was at 44 percent at this juncture -- although his chief rival, Dole, was just nine points behind. And in 1980, Ronald Reagan was 21 points ahead of his closest rival -- 41 to 20 percent over Howard Baker -- at a comparable moment.

But then there's Romney, who still does well to break 25 percent in polls, even though his competition seems laughably weak. (A new Wall Street Journal/NBC News poll does have Romney edging up to 32 percent, but the methodology is different than most other polls -- it's based on re-interviews with some previous respondents.) The only other modern nominee who was in a similar situation at this point was John McCain. Seven weeks before the 2008 Iowa caucuses, McCain was averaging about 15 percent in national polls. He wasn't seen as the inevitable winner -- his campaign had been declared dead by most pundits over the summer -- but he was one of five Republicans who were (more or less) considered in the mix, along with Romney, Fred Thompson, Rudy Giuliani and Mike Huckabee.

McCain's national poll numbers didn't move much until the primary season officially began. On the eve of Iowa, he was averaging 20 percent, a figure that slowly rose as he one development after another broke his way. After winning New Hampshire, McCain jumped to 30 percent. When he won Florida -- after which Giuliani dropped out and endorsed him -- he surged to 43 percent, 18 points ahead of Romney. And when he knocked out Romney with a big Super Tuesday, he finally pushed to 49 percent in the national horse race, 21 points ahead of his last serious rival, Huckabee.

The key is that this upward trajectory could have been arrested and reversed at several different points. What if Romney had won Iowa, instead of suffering a humiliating loss to Huckabee? Then it might have been Romney who went into New Hampshire with a burst of momentum. And if Romney had then beaten McCain in New Hampshire, then it would have been curtains for the Arizonan. Or what if McCain had fallen in South Carolina (where he only beat Huckabee by three points) or Florida (where he edged out Romney by five)? Losses in either or both of those states would have prevented him from gaining new national support and boosted a rival candidate instead.

That McCain story may be worth keeping in mind now, because Romney seems to be following a similar path. The resistance of a major chunk of the GOP to Romney now seems undeniable. This doesn't mean the holdouts won't ultimately come aboard, but like with McCain in '08, they're going to make him work for it in the primary season. The good news for Romney is that his opposition seems weaker than McCain's. A swing of a small number of votes in one or two states in 2008 could easily have led to a different candidate being nominated.But if one of the non-Romney candidates gets hot in an early contest this time around, the more likely result is that party leaders will simply redouble their efforts to prop up Romney, not wanting to nominate an unelectable candidate. Here the Dole '96 parallel may be apt; despite his wide national advantage, Dole actually lost New Hampshire to Buchanan that year -- a result that ended up hastening Dole's nomination, since even most conservative opinion-shapers saw the folly in anointing Buchanan, who didn't win a single contest the rest of the way.

Still, a lot has changed within the GOP since '96. And Buchanan, with his isolationist streak, was out of step with the conservative base on several major issues. Most of Romney's current rivals aren't. Given the new prominence of purist Tea Party-types within the GOP, it seems worth wondering whether there really would be an overwhelming "Stop him!" cry from the party's opinion-shaping class if, say, Herman Cain or Newt Gingrich were to upset Romney in an early contest or two.

Ed Kilgore made this case recently, arguing that in the Tea Party-era GOP, "candidate credentials like broad name ID or prior experience or early-state positioning or even money have become vastly less important than fidelity to an exceptionally narrow set of conservative principles." In other words, even if Newt really has been using this campaign mainly to sell books and videos, why should that mean Tea Party Republicans will automatically reject him -- especially if they think he's the best at the debates and the conservative commentators they listen to are all talking him up?

That's the nightmare scenario for Romney: that he says and does all of the right things in every debate and speech, that he assembles the best-funded and best-organized political operation, that he racks up the most endorsements, and that his opponents all flunk the conventional tests of plausibility -- and that it still doesn't matter to the Republican Party of 2012.

Shares