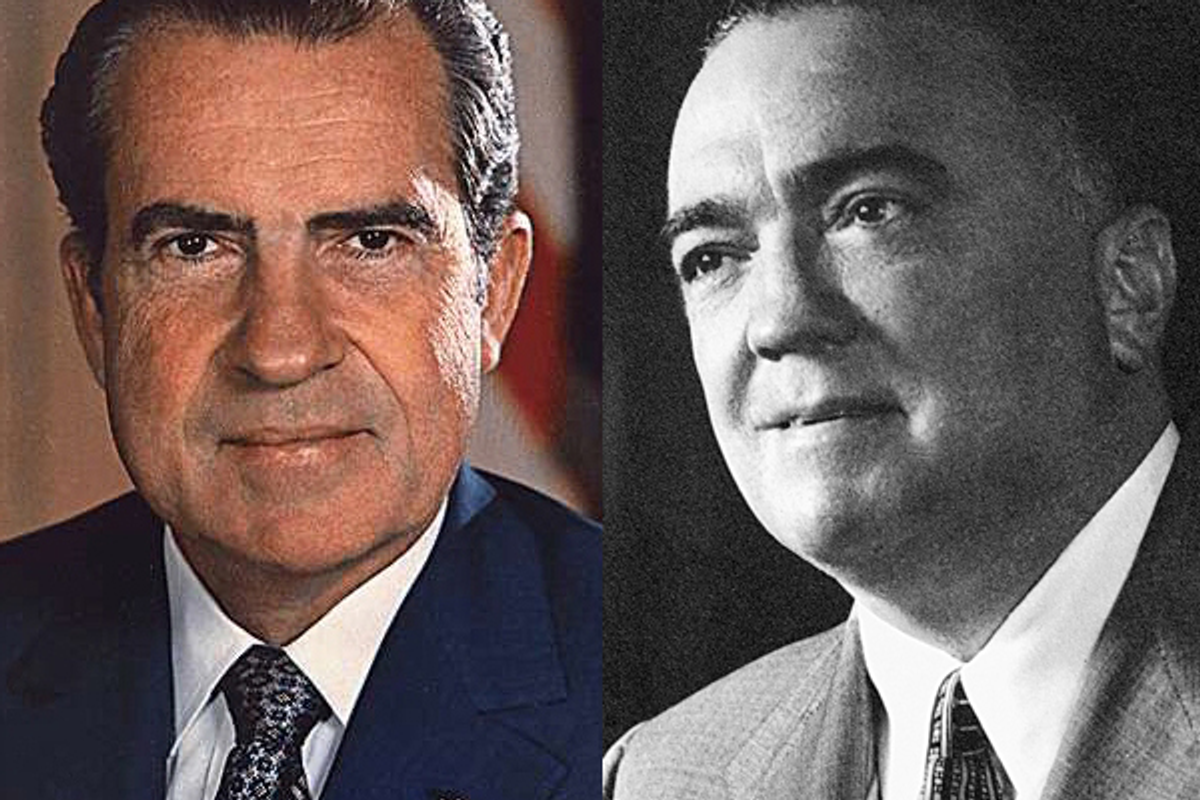

J. Edgar Hoover passed away on May 2, 1972. The legendary FBI director lay in state at the Capitol rotunda, the doors kept open all day and night for the convenience of mourners.

I remember because I was still at college in Washington then, and around 3 o’clock in the morning a bunch of us drove up there, not to pay our respects, but to make sure he was really dead.

In those pre-9/11 days, you could still do that sort of thing.

The memory of our predawn visit came rushing back last week as I introduced a screening of “J. Edgar,” the new film directed by Clint Eastwood, and interviewed its screenwriter, Dustin Lance Black, who won the Oscar a couple of years ago for the movie "Milk."

There’s a sequence toward the end of "J. Edgar" right after Hoover dies: President Richard Nixon appears before the cameras to solemnly announce the news. Cut to Nixon in the Oval Office ordering chief of staff Bob Haldeman and other members of his Praetorian Guard to seal off Hoover’s offices and seize his fabled stash of secret files on every prominent politician, past and present. Meanwhile, Hoover’s faithful secretary, Helen Gandy, has locked herself away with a shredder and dutifully eliminates the evidence.

The movie loops chronologically back and forth across Hoover’s law enforcement career of more than half a century. Eastwood and Lance Black maneuver an intriguing tightrope walk between the Hoover who sees himself as a crime-busting patriot protecting his country and pioneering forensic investigative techniques, and the paranoid, power-mad, status-obsessed Washington insider who would go to any lengths to pursue anyone he thought subversive or simply critical of him and his methods.

And all of this was crammed into a repressed, mother-ridden, lonely, anguished individual whose decades-long relationship with his second-in-command, Clyde Tolson, was the closest he ever got to real love – at a time in America when you could walk into the Capitol building unchallenged by security but homosexuality truly was, as the old cliché goes, the love that dared not speak its name.

As Lance Black told the San Francisco Gate in a recent interview, “If you are robbed of the ability to love who you love, you will fill that hole with something else. For him, it was power and a nation’s admiration ... he started to do things that were heinous to hold onto it.”

David Denby adds in his review of the movie in the New Yorker, “Again and again, he goes too far, treating Communist rhetorical bluster as the first stages of revolution, assembling lists of people whose opinions he considers suspect, fabricating documents, planting stories in the newspapers, bludgeoning potential enemies with his file drawers of sexual gossip” – files that notoriously included John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., not to mention Louis Brandeis, Eleanor Roosevelt, Albert Einstein, Marilyn Monroe and Mary Pickford.

According to attorney Kenneth D. Ackerman, author of “Young J. Edgar: Hoover and the Red Scare,” by 1960, “the FBI had open ‘subversive’ files on some 432,000 Americans.”

Last week, as if cued by the release of “J. Edgar,” there were new developments in the life stories of both Hoover and Nixon. By way of a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, the Los Angeles Times received old FBI files on Jack Nelson, the journalist who eventually became that paper’s Washington bureau chief.

“Hoover was convinced -- mistakenly -- that Nelson planned to write that the FBI director was homosexual,” the Times reported. “As he had done with other perceived enemies, Hoover began compiling a dossier on the reporter ... John Fox, the FBI's in-house historian, said Nelson arrived on the scene at a time when Hoover was feeling vulnerable. A published report that the director was gay could well have ended his career, and that possibility -- unfounded or not -- had Hoover on edge.”

In memos, Hoover, who had a penchant for smearing his real and imagined nemeses with names from the animal kingdom, variously called Nelson a jackal, rat and – most charmingly -- a “lice-covered ferret.” He tried to have the reporter fired and met with the paper’s head man in Washington, Dave Kraslow. "The spittle was running out of his lips and the corners of his mouth," the now 85-year-old Kraslow recalled. "He was out of control."

Kraslow refused to fire Nelson but did ask him to send Hoover a response, which read, in part: "I emphatically deny that I have at any time under any circumstances ever said or remotely suggested that Mr. Hoover was a homosexual."

Meanwhile, the National Archives released the latest batch of tape recordings and transcripts from the Nixon Presidential Library, also known as the House of Mirth.

Among the treasures untroved was the 278-page transcript of Nixon’s grand jury testimony in June 1975, part of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force’s investigation into what litigator and author Glenn Greenwald calls in his new book, “With Liberty and Justice for Some,” “one of the clearest cases of widespread, deliberate criminality at the highest level of the U.S. government.”

There are no smoking guns in the new materials, but at a time when -- in comparison to the current crop of GOP candidates -- Nixon’s reputation is undergoing a bit of a positive face-lift, it’s always good to be reminded of the whiny, self-pitying, defensive, dissembling reprobate we knew and loathed back in the bad old days.

He brushes off the whole sordid scandal as “this silly, incredible Watergate break-in” and says, “I want the jury and the special prosecutors to kick the hell out of us for wire-tapping and for the plumbers and the rest because obviously you may have concluded it was wrong.” So sayeth the man made safe from prosecution by a presidential pardon.

He tells the grand jurors and investigators that he was upset about the White House tape with the infamous 18 and a half-minute gap (it was of a conversation between Haldeman and Nixon three days after the burglary attempt) – not because of the erasure but because he mistakenly thought it wasn’t going to be turned over to the authorities. “I practically blew my stack,” he blusters, claims the gap was an accident and that he had no idea what was discussed in those missing minutes, then blames the whole thing on his own faithful secretary Rose Mary Woods. What a guy.

Certainly, nothing in the freshly released Dictabelt tapes and transcripts changes what we always figured -- Nixon was not contrite over any of it but simply angry that he’d been caught. “It’s time for us to recognize that politics in America ... some pretty rough tactics are used,” he says. “Not that our campaign was pure ... but what I am saying is that having been in politics for the last 25 years, that politics is a rough game.”

He speaks about using the IRS to investigate Democratic campaign donors and the ease with which he could raise massive cash contributions from big business. He denies swapping ambassadorships for political donations but notes, “Some of the finest ambassadors ... have been non-career ambassadors who have made substantial contributions." In that simultaneously priggish but smarmy way of his, Nixon recalls that President Truman made Washington social maven Perle Mesta ambassador to Luxemburg not “because she had big bosoms. Perle Mesta went to Luxemburg because she made a good contribution.” (Her appointment was immortalized in the Irving Berlin musical "Call Me Madam.")

Perhaps the strangest artifact in the latest document dump isn’t the grand jury testimony but Nixon’s recollections of the famous incident at the Lincoln Memorial in 1970 early on the morning of a massive antiwar demonstration just days after the killings at Kent State. He paid an unannounced visit to the monument and talked with a group of the student protesters camped out nearby.

“I know you, probably most of you think I’m an SOB but, ah, I want you to know that I understand just how you feel,” he says he told the demonstrators. “What we all must think about is why we are here ... What are those elements of spirit which really matter?

“... I just wanted to be sure that all of them realized that ending the war and cleaning up the city streets and the air and the water was not going to solve the spiritual hunger which all of us have, and which of course has been the great mystery of life from the beginning of time."

As he leaves, he tells one of the students, "I just hope your opposition doesn't turn into blind hatred of the country. Remember, this is a great country for all of its faults."

Of course, as Nixon got down with the kids, J. Edgar Hoover’s counterintelligence program, COINTELPRO, was getting down and dirty, not only spying on and infiltrating the antiwar movement but also deliberately trying to subvert and disrupt it -- with Nixon’s approval.

Such violations of civil liberties echo through to the present day: obstructions of justice, abuses of power, the tapping of emails and phone calls, black site detentions and “enhanced interrogations,” to name just a few. In his new book Glenn Greenwald recalls the words Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, John: “Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could.”

J. Edgar Hoover and Richard Nixon remind us of that essential truth. They’re not so dead after all.

Shares