Simon Weisenthal's greatest contribution to the world was his dogged pursuit of Nazi criminals who escaped punishment at the end of World War II. His second greatest contribution was his reminder that despite being described as "the Good War" or "a just war," not enough good was ultimately done, and comparatively little justice was meted out. Some of the most prominent and heinous architects of mass murder simply got on with their lives, and some were the recipients of largesse -- jobs, travel assistance, even money and government protection -- that was denied to the people who endured their cruelty. And we tend to forget that for every high-ranking sadist or mass murderer who was imprisoned or executed after the war, thousands more who assisted them directly (through action) or indirectly (through silence) were never even called to account.

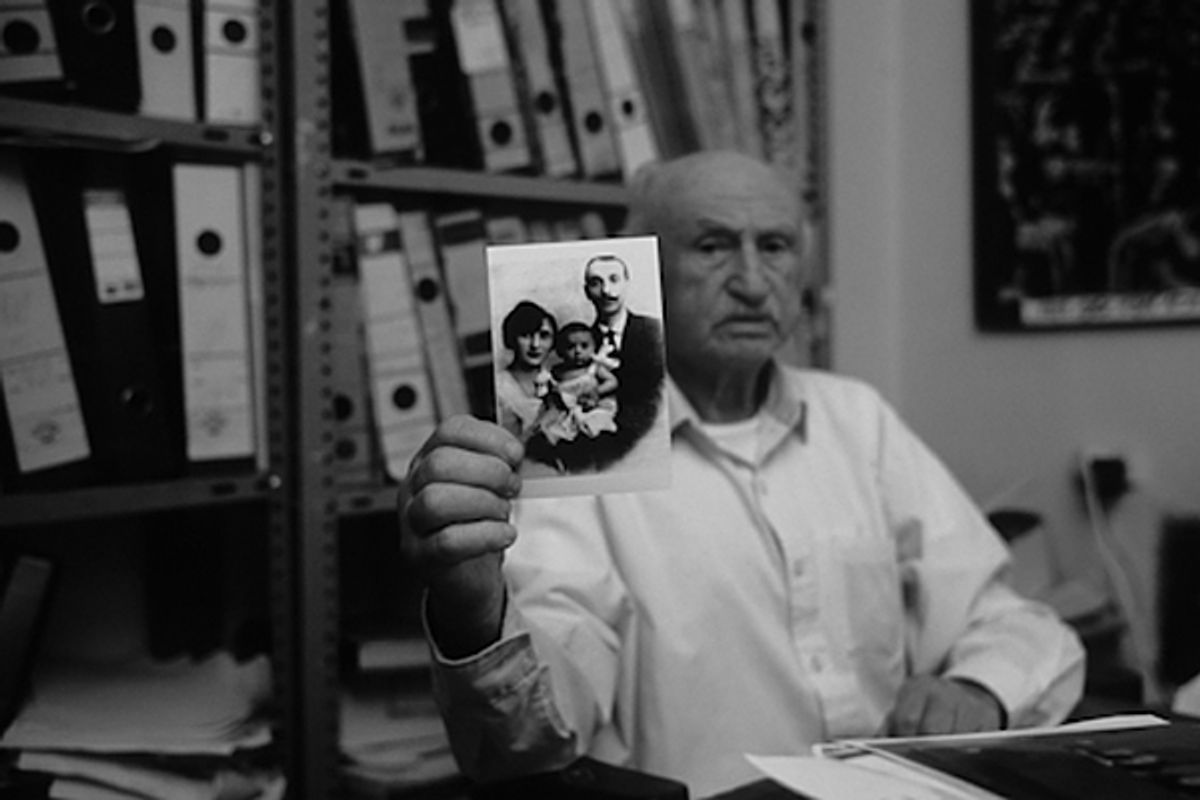

This grim fact is the jumping-off point for "Elusive Justice" (Tuesday, PBS; check local listings), a documentary by Jonathan Silvers about Holocaust survivors (and victims) and the German war criminals that still weigh on their minds nearly 70 years after the end of the war. Narrated by Candice Bergen, the movie hits some of the expected topics and people, including the Nuremberg Trials and the efforts of Weisenthal (who disliked being called a "Nazi hunter" because so much of his work consisted of sifting through documents) and Asher Ben Natan, who funded and organized ex-Nazi-tracking operations in Europe.

But for the most part, the movie loiters around the edges of the best-known events, delving into stories that we haven't heard before, and philosophies and feelings we rarely hear articulated in a documentary like this one. And it pays special attention to the mid-level officers, party officials and anonymous citizens who carried out orders from the top. Some of these people fled to other countries after 1945, but most returned to their pre-war lives. One survivor asks, "Why the hell should they sleep like babies while I have nightmares?"

The film contains much unresolved discussion of the difference between justice and vengeance, and how the Nuremberg tribunal was created in order to head off an international wave of vigilante mayhem. A couple of once-persecuted Jews who killed Nazis during and after the war offer a spirited defense of vengeance. At one point the film suggests that despite the noble intent behind the Nuremberg Trials, they might have inadvertently hurt the long-term cause of justice, by making most of the world subconsciously believe that it was all over and the good guys won and there was no need to trouble our minds with any of it.

One of the movie's subjects is an elderly Viennese man who narrowly survived being euthanized at the notorious Am Spielgelgrund clinic, where children deemed "undesirable" by the government were experimented on or killed and then dissected. In 1997, when the filmmaker was an ABC News producer, he managed to track down Dr. Heinrich Gross, who once ran the clinic, and interviewed him on a public street. "If you didn't do what you were told, you would have been killed by the Nazis," the elderly doctor said at the time -- the justification of so many mid-level participants in war crimes. Three years after the ABC report aired, the doctor was charged with complicity in mass murder. The trial ended four days after it started when the presiding judge declared Gross medically unfit to stand trial. He died in his home in 2005. "And that was our so-called justice," says one of the doctor's victims.

Shares