I have been returning to Idaho's Wood River Valley for 20 years, always to the same house on the river where my parents live. I’m older, my parents are older, but mostly little has changed. Each holiday season, I come home from different cities, different countries, and everything is still beautiful. The air is still clean. We leave the front door unlocked. The propeller plane glides up the valley and lands at the little airport. My mother and father pick me up. We eat dinners together. We take walks in the snow. We ski. I see my friends. And then I return to my life, wherever that is.

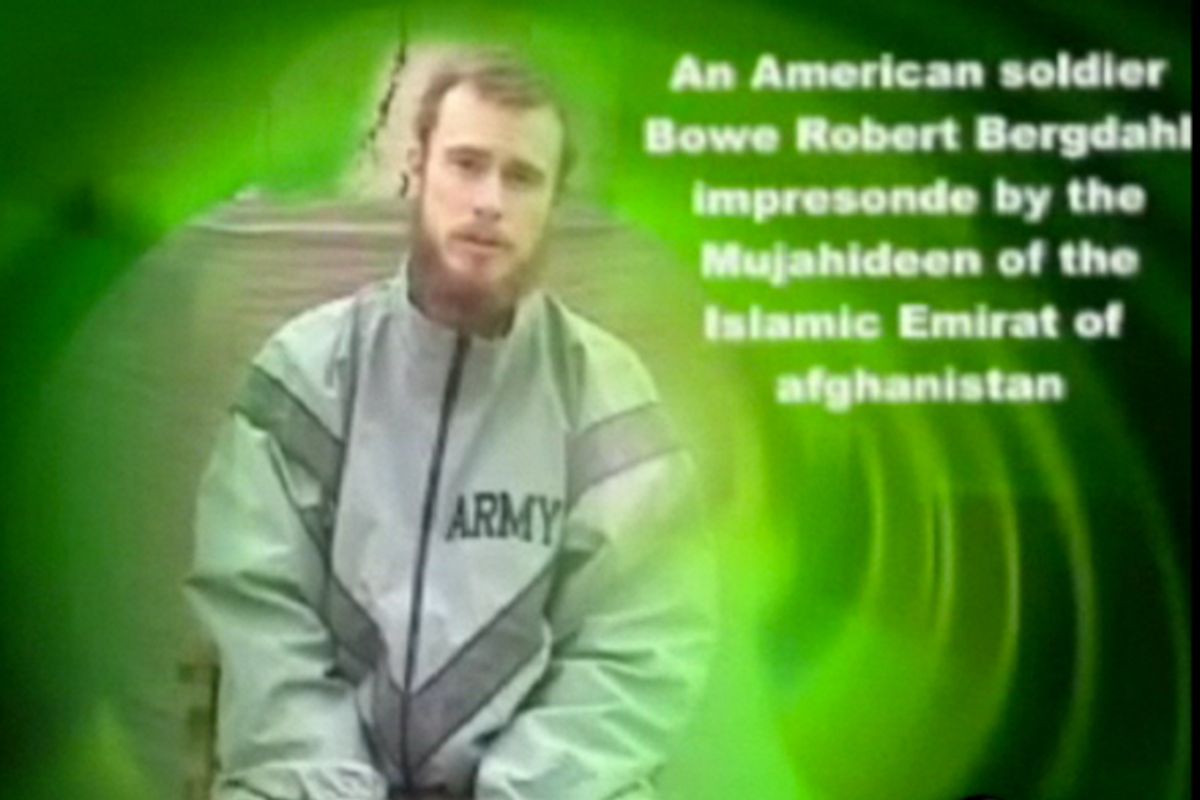

Two years ago I came home to yellow ribbons tied on trees. A young man who grew up in this valley had vanished from his base in Afghanistan. Not long after that the Taliban released a video of him sitting on a floor, eating the way a child eats when he’s being made to finish his dinner. Bowe Bergdahl has been in Taliban captivity now since June 2009; he is our only prisoner of war in Afghanistan.

The young man speaks. He says, “Well, I am scared. Scared I won’t be able to go home. It is very unnerving to be a prisoner. I have my girlfriend who I was hoping to marry. I have my grandma and grandpa. I have a very, very good family in America that I love and I miss them every day that I’m gone.” He seems terrified. He begins to cry. He says, “I miss them, and I’m afraid that I might never see them again and that I’ll never be able to tell them that I love them again, never be able to hug them.”

I’ve never met Bowe Bergdahl. I’m much older than he is, but we were both boys in the same town. We both know the same lakes, the same sky. We’ve both stood around a bonfire far out in the green woods with our friends, drinking beer, hoping the cops wouldn’t come to send us all home.

Terrible things have happened in this idyllic valley. Children have died in car accidents and avalanches. There have been murders. Devastating fires. While superstition says not to write such things, it feels important now to write this: None of those terrible things ever happened to me. To my family. I have been fortunate beyond measure, beyond reason, beyond odds. We are all alive. We are all healthy. We see each other often. We have far more than we need.

I don’t think of Bowe Bergdahl all that often. But this winter, as the plane turned up the valley, the hills white with snow, as it began to bump and fall in the updrafts and I could see our shadow racing below as we descended so low that it seemed as if the wings might clip the hills, I thought of him. I tried to imagine what it might be like to live the way he has these last two years – imprisoned so far from home, entirely absent from his family, 25 years old. I imagine him healthy and alive.

Last spring, the young man’s father stood outside to record his own video against a backdrop of snow melting on brown hills. And now, as I sit in my parent’s warm house, my mom cooking dinner, my dad reading in his chair, I watch Bowe Bergdahl’s father walk into the frame.

He’s wearing a thin black shirt buttoned to the throat. The wind is blowing. His beard is long and wild. There is the eerie sound of a bird chirping. I know those hills. They seem to find their way into nearly everything I write. The mountains in this valley are spectacular, but it’s always those hills that I think of when I miss home. They change with rain and light and snow. They become women and great lumbering animals and water.

His father says, “I am the father of captured U.S. soldier Bowe Robert Bergdahl. These are my thoughts.” He is measured and calm. He acknowledges the suffering of the Pakistani people. “The violence of war, earthquake, epic floods and crop failures have devastated your lives while our son has been in captivity. We have watched your suffering through the presence of our son in your midst,” he says. “I pray this video be shown to our only son.” In Pashto, he says Stayray me she, Bowe.” Hello, Bowe. “We love you. We have been quiet in public, but we have not been quiet behind the scenes. Continue to be patient and kind to those around you. Her Na, Bowe,” he says. “Her Na. You are not forgotten.”

He bows his head and the video ends.

I watch him over and over again, trying to imagine what fear, what helplessness, what loss he must feel. It is impossible. As impossible as it is to imagine what his son feels locked away, wherever he is. And I imagine that somehow the young man is still alive, that he sees this video his father has recorded, sees those hills in the background and can feel the air of home, can smell it, can see in swaths of snow still melting in the shaded ravines that the hills will turn green soon, that the changing seasons here await his return.

Shares