Doctors routinely meet with patients who make requests for specific medicines, tests and referrals to specialists. In this era of the Internet, consumer-driven healthcare and direct-to-consumer drug marketing, this is no surprise. And while an informed patient is a good thing, what may surprise you is just how hard it is for doctors to say no when a patient makes a specific request for something he or she doesn't really need.

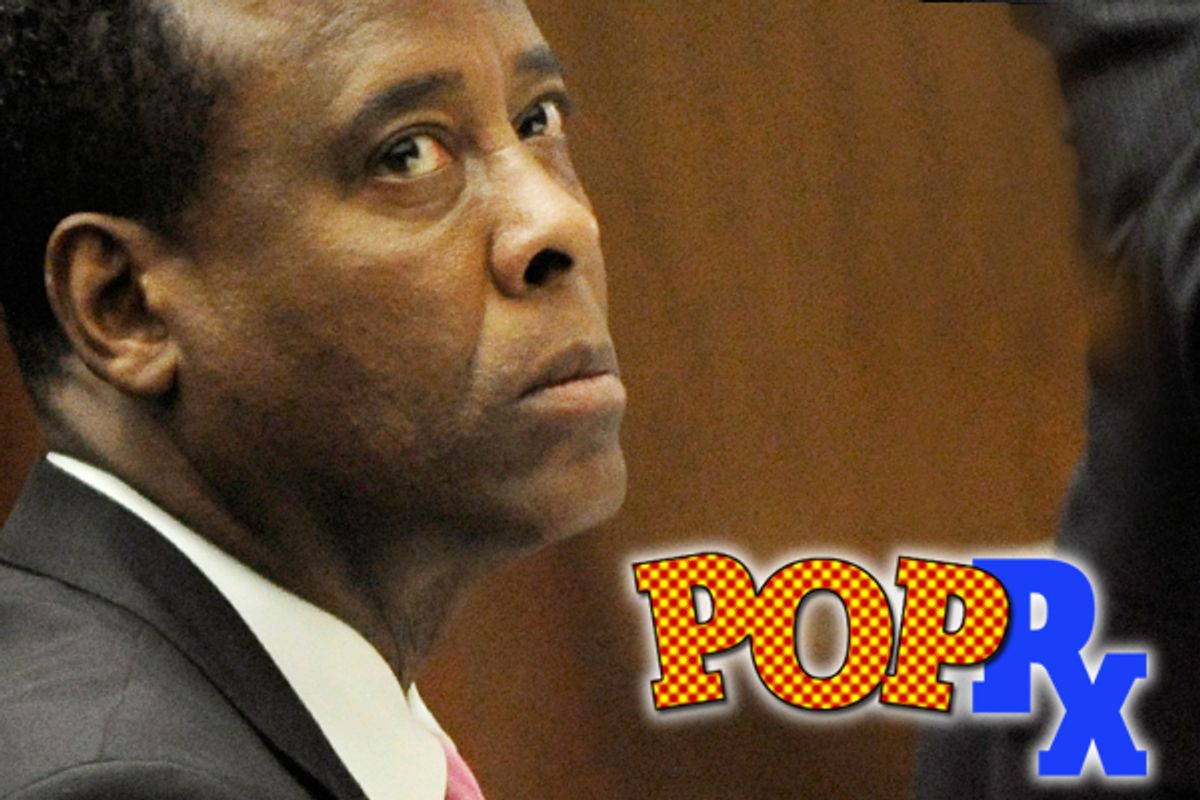

Right now, Dr. Conrad Murray sits in jail because he couldn't say no to Michael Jackson when Propofol came up in conversation between them. But even doctors who aren't tempted by an enormous monthly retainer and access to one of the world’s biggest celebrities are challenged by the word "no."

American medicine is a business -- but a weird one. In any other sector of our economy, businesses are determined to give their customers what they want, however they want it. But in medicine, the “have it your way” mind-set doesn’t always jive. First, physicians have a duty to avoid doing harm. The choice of a drug or test based solely on a patient’s request can undermine that. Second, as everybody knows, we spend a big slice of our GDP on healthcare. Since the person who has control over expensive tests and the prescription pad is your doctor, there's ever-increasing scrutiny to be responsible stewards of healthcare dollars.

All these factors come to life in the exam room. Case in point: I periodically get requests from parents to prescribe cough medicine for their child that contains codeine. Besides the codeine, the drug contains alcohol, naturally leading to a better night’s sleep for child and, hence, the exhausted parent. But there’s no evidence that this cough medicine helps the child get better any faster, and it may even be dangerous. Should I prescribe it or not? The evidence says no, but to say that can lead to a confrontation with an angry parent. Though cough medicines aren't expensive, if it's hard to say no to something that simple, it's even harder when the stakes are higher -- an unneeded new drug, a CT scan, a referral to America’s top cardiologist.

The phenomenon of how requests impact the patient-doctor relationship has been studied extensively by Dr. Richard Kravitz at the University of California at Davis. Kravitz’s research has shown that somewhere between 10 and 25 percent of patients bring a specific request to their doctor (the high end of that range is between a patient and his or her primary care doctor). Here are some of his sober conclusions: Patients who do not have their requests met rate their physician lower, are less likely to adhere to their doctor’s recommendations, and use more healthcare resources than those who do get their request.

Physicians who encounter the patient with a request report those visits to be stressful and unsatisfying as well. But if you’re wondering who wins, Kravitz suggests it’s the patient, though just slightly. He and his team looked at how doctors responded to patients’ requests for an antidepressant medication. Fifty-six percent of the time, patients got the drug they wanted.

Why is it so hard for doctors to say no? To be honest, it’s often just easier to say yes. Usually, we’re behind schedule, with a waiting room full of impatient customers, and we have a desk full of phone messages to return and charts to finish. To take even a few extra minutes and open the conversation -- even a confrontation -- about a request is time and energy we don’t want to expend. So we put pen to paper, rip the script off the pad and hand it to them as we rush out the door.

The other thing is that nobody really teaches us how to say no. It seems ridiculous, but neither Kravitz nor I could remember an instance during medical school or residency when we were coached about how to manage inappropriate requests from patients. Many of us probably figure out ways to parry the patient over time, but not without inflicting some damage. Back to the example of cough medicine requests for kids: I remember earlier in my career when, on a very stressful day, I walked into a room with a teenage girl and her mother. The mother directly asked for a codeine-containing cough syrup. I knew better, and I wasn’t about to let this parent have it. “No. Look,” I bluntly replied, “it only works because it contains alcohol. Why don’t you just go out and give her a glass of Scotch.” It was not my best moment doctoring. I’ve taken a long and bumpy road since to get better at managing patient requests. These days, I’m more likely to explain the issue, decline the request, ofter an alternative, apologize for any inconvenience, and make sure they know they can always seek a second opinion.

Kravitz’s research, in fact, does reveal that there are ways to say no that are better for both doctor and patient. In Kravitz’s aforementioned study where patients requested an antidepressant, he was able to categorize how doctors handled patient requests. The most successful method is for the doctor to exercise a little curiosity and delve deeper. It’s not surprising, for example, to find out that a patient who comes in with headaches wanting an MRI had a friend or relative who died of a brain tumor, or one with a cough who wants an antibiotic who knew someone hospitalized with pneumonia. If both patient and doctor can get to the root of the request, they can, in many cases, discuss it and figure out a third way.

The second way doctors in the study managed patient requests was to try to order some tests. While it can be a successful strategy to look for “objective data” to help reassure a patient, it isn’t always cheap or safe. Labs and X-rays don’t cost much individually, but the volumes of them that doctors order add up fast. Unnecessary tests beget more unnecessary tests. For example, if I order blood work for a patient who I don’t really think needs it, and one of the numbers -- one that has nothing to with why I ordered the test -- comes back slightly off, I’m stuck having to call the patient and tell them to repeat the test, even if the child is completely fine now. All of us have had a test or radiology result we ordered just to satisfy a patient come back to bite us like this.

Kravitz and I both agreed that “patient-centered care” or “shared decision-making” are euphemisms for negotiation. And perhaps, like other professionals, we in medicine ought to focus more on negotiation tactics (Kravitz’s last paper is called “Getting to ‘No,’” a riff on the famous business book about negotiation called “Getting to ‘Yes’). This may sound coldly corporate to the average patient who has ever wanted something from their doctor, but it’s a reality we need to address. In pediatrics, where limiting the overuse of antibiotics is a priority, it’s recommended that doctors not prescribe drugs in most cases of middle-ear infections. Instead, since evidence suggests most ear infections get better on their own pretty quickly, we can treat a child’s pain with over-the-counter drugs like ibuprofen. But just in case things don’t get better, we often keep an antibiotic prescription ready for the child for the parent to fill. Doctors call it a “safety-net prescription,” but MBAs know it as a contingency -- a common negotiating tactic to satisfy both parties during a negotiation.

Finally, for doctors who are still entrenched in the belief that patients shouldn’t be asking for anything, or for patients who are too timid to speak up, Kravitz has some interesting findings: In cases where the patient had a specific request but didn’t make it because they were uncomfortable, pressed for time, or because the doctor’s bedside manner didn’t afford the chance, that patient left less satisfied. Doctors, too, rated the visit where something was left unsaid as more difficult.

The lesson here is that it’s best for the doctor and the patient to get everything out in the open, and for a healthcare system that affords the right amount of access and time -- especially in primary care -- to make that to happen.

Shares