AUSTIN, Texas -- Under a photovoltaic glass trellis, on the terraced steps of Austin’s modernist City Hall, dozens of occupiers sprawl amid sleeping bags and sleeping dogs. A few people tap on computers while others nestled in bedding sit up, looking as if they are slowly sloughing off a hangover. It’s about 4 in the afternoon.

Trying to escape the pungence of fermenting compost, I gingerly climb the steps, scooting around one young woman with a brown sweater knotted around her waist and blue jeans around her ankles. A few feet away, a wiry guy in a flower-print sundress with body hair spilling out like Borat in a mankini strums a guitar.

At a table that passes for the kitchen on the plaza below a hefty man with a bandanna hanging off his chin eagerly offers mashed beans and vegetables on bread to passersby. A dozen homeless youth pass around a bowl as three impassive cops hang on the edge of the occupation. Two older women waltz to music only they can hear and a shirtless man grabs his shorts with one hand and a protest sign with the other as he chases a death-defying dog across four lanes of traffic.

When I describe the scene to Michelle Millette, an organizer with Occupy Austin, she laughs and in a rising voice says, “Keep Austin weird!” She explains that the encampment, which is mostly street people, stems from the fact that “Austin has a huge homeless population. A lot of the people are there because they say, ‘This is the only place I can legally sleep because I’ve been chased out of everyplace else.’” Plus, Millette adds, because the city has banned tents, “it looks like a hobo camp to people walking by. Many people are afraid to leave their stuff because it’s just lying out there.”

The homeless population may also be the city’s stealth tactic to undermine the occupation. On the night of Oct. 29, Austin police swept 37 occupiers off to jail under the pretext that they were in violation of new food distribution rules imposed the day before. Millette says they were given criminal trespass warnings that have prevented arrestees from returning to the City Hall plaza until the charges are dismissed. She says, “This created a rift between people who were allowed on city hall and those who were exiled from City Hall.” Since then, “We’ve been figuring out solutions to these issues and coming together.”

Canned quirkiness

As for “keep Austin weird,” she says it’s the slogan of local businesses that are trading off the “canned quirkiness” of Gen X slackers, Gen Y hipsters, everything imaginable on a taco, and indie music that have made this city of 790,000 famous.

Throughout the South, as in much of the country, many local economies subsist on marketing their version of canned quirkiness to tourists: In Lexington, Ky., it’s horses; in Nashville it’s country western music; in New Orleans it’s public bacchanalia.

Mayor Lee Leffingwell touts Austin as “the creative capital of the world.” Some experts claim such “creative cities” are the natural evolution of the post-industrial economy. But the notion that we can all be successful artists, code writers, Web designers, performers, writers, musicians or restaurateurs is unrealizable because creative cities need hordes of tourists to consume their products. What’s mostly left for everyone who does not belong to the creative class are low-wage jobs, often monotonous and unstable, in the service sector.

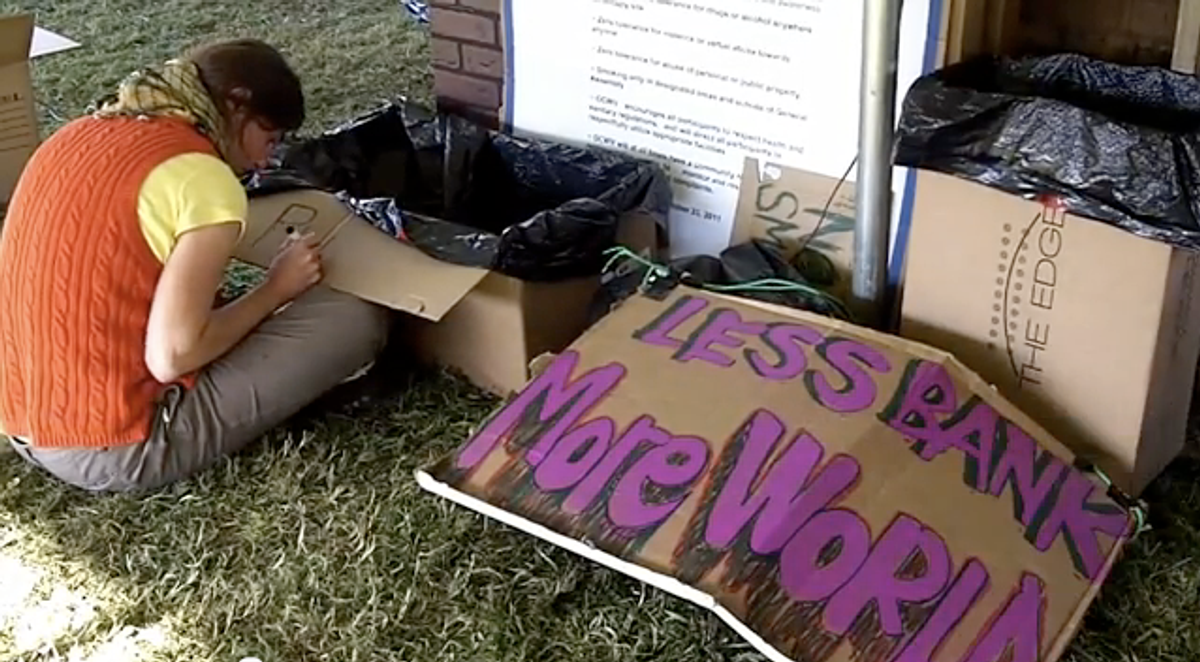

In every city we’ve been to, people say the lack of well-paid jobs, or any jobs at all, piqued their interest in joining the occupation. The service-sector economy is the flip side of the Wall Street economy, which only seems to excel at making weapons of mass destruction, whether bombs or collateralized debt obligations.

Trying to build a solid economic future on tourism is a losing proposition. Bureau of Labor data finds that a few service-sector occupations paying $8 to $11 an hour on average – cooks and food preparers, waiters and waitresses, janitors and maids, cashiers and retail salespeople – employ more than 17 million people in the United States. This outstrips the 13 million employed in all construction, extraction and production industries.

“America doesn’t make anything anymore” is the bitter summation of many occupiers when they talk about what’s wrong with this country. The United States doesn't make appliances or shoes or jeans or robots or cosmetics or furniture or computers or ships or solar panels or you name it. Following decades of offshoring, only 9 percent of Americans are employed in manufacturing; before World War II it was 30 percent.

What’s left is an economy that moves goods, vehicles and people around a huge country; services of cheap food, gas and lodging; and a workforce barely scraping by. The result is 25 million Americans looking for full-time employment and 100 million Americans living in poverty or “near poverty.” In other words, the heart of the 99 percent.

Austin's city limits

Austin, for example, is known as “the Live Music Capital of the World” with more than 200 live music venues, 1,900 bands and performers as well as the "Austin City Limits" television program, and the South by Southwest Music Festival. The growing leisure and hospitality industry is one of the city’s largest sectors, employing around 90,000 people. Its lodging and food sales are about twice as high as those of the rest of Texas.

Millette says while “there is a lot of nightlife [in Austin]. There are very few well-paid jobs in that sector, so a living wage is a big issue for us. A lot of people work two, three or four jobs.” She says that in response Occupy Austin has organized “marches with labor around lost jobs,” such as in the tech and public sectors, and to agitate for a living wage, which mainly affects Austinites in the service sector.

Though, Millette adds, the issue is not so much with local businesses that “are all about being progressive so they want to provide a living wage.” The problem is with “huge corporations that post huge profits but don’t pay a living wage. The money goes out of the community.”

Austin’s hospitality industry has the fastest job growth of any sector, having added 4,500 jobs in the last year, but Millette says “not everyone is going to get a job even if they play by the books.” An article in the Statesman describes the glut of job applicants. Austin’s Gatti’s Pizza opened a new eatery and received more than 200 applicants for 25 positions while Emo’s, a live-music venue, says it gets 50 to 100 job inquiries a week.

For the homeless camped out in City Hall plaza, their prospects are dismal. “A lot of people have fallen into homelessness and can’t scratch their way back up,” says Millette. Many have tried to “clean themselves up and get a job,” but because homeless people don’t have an address and often lack a phone and email they can’t even apply for jobs.

Yet it’s difficult to see how jobs tending bar or making tacos, which, with luck, might pay $15 an hour but still lack stability and real benefits, is going to provide a model for development. Like the rest of America, Austin is becoming a city deeply divided by race and class. Or as Austin’s city demographer puts it: “socio-economic spatial segregation has steeply increased.” The western part of the Austin region is white, wealthy and Republican. The city core is mostly white, Democratic and wealthy, while the outlying eastern regions are poor, Democratic and Latino.

It is Austin’s quirkiness that has accelerated the gentrification model of development tourist dollars and rising housing costs that push the poor and brown to the margins, many of whom were present at the occupation.

In Kentucky, "a playground for the rich"

In Bourbon County, just north of Lexington, the rolling lands sprout wealth. We dip and twist on narrow country roads bounded by elegant horse farms. We’re on our way to have lunch with C.E. Morgan, a native of the region and author of the award-winning "All the Living." She’s working on her second novel, set in Kentucky’s horse country, and over catfish po’ boys and pulled pork on the back porch of Windy Corner Market we talk about all things equine.

It is difficult to exhaust superlatives when describing Lexington, “Horse Capital of the World.” Top colts can sell for more than $10 million, well over $1 billion worth of horses are auctioned a year, the industry adds $3.5 billion a year to the state economy, and employs 96,000 people as well as being a vital part of Kentucky’s $8.8 billion tourism sector. Some of the most lavish farms are owned by royalty, such as Dubai’s ruler Sheikh bin Rashid Al-Maktoum, who dropped $60 million at one yearling auction in 2006 to populate his 4,000 acres of Kentucky bluegrass.

Morgan says “you can grow a strong horse” in Fayette County, which surrounds Lexington. “This is some of the best agricultural land in the country. The fertility of the inner bluegrass can be attributed to limestone composed of just calcium carbonate and phosphate. Bone builders. Add to that the karst landscape full of sinks, streams and springs and you have the perfect recipe for horse farms.”

The rolls and folds of the inner bluegrass are partitioned by winding white-washed fences, which Morgan explains signifies wealth because they are harder to upkeep than black fences. Sprawling manors are tucked away from the road and sublime thoroughbreds nibble at the grass. But the idyllic landscape hides an ugly “back stretch,” the area behind the racetrack where abusive conditions are the norm. It’s one of the deadliest sports for horse and animal alike, with 24 jockeys having died during races in the 1970s alone. Morgan describes frequent drug abuse and deaths as jockeys struggle to make weight of 112 pounds.

One study calls the language of the back stretch as Spanish. Since the 1970s, undocumented migrants, mainly from Mexico and Guatemala, have replaced African-Americans as groomers, stable hands, “hot walkers” and exercise riders that are “unregulated … and characterized by informality.” Not surprisingly, wages are under $300 a week for some positions, “their jobs are dangerous, and very few have access to health care because they lack insurance or cannot afford treatment.”

While at Occupy Lexington, locals decried taxpayer subsidies for “the Sport of Kings,” costing the state more than $220 million in revenue from horse sales alone in the last decade. However, the subsidies do preserve the picturesque lands. Near Lexington pockets of McMansions dot the countryside. Morgan says developers used to scoop up horse farms to build residential homes, but this has been mostly halted by zoning laws that maintain large plots unaffordable by the middle class.

Morgan says, “The extraordinary beauty of the region has been preserved by land management choices that effectively restrict the area to the wealthy, who own the horse farms. As a result, the delicate ecology is preserved, but 70 percent of Fayette County is a rich man's playground. There is almost no public use of that land.”

Unlike Austin’s entertainment economy, Lexington’s horse industry is staggering from the economic crisis. Racing purses are shrinking, sales are dropping and the number of horse farms for sale is rising. All of this ripples outward with the usual decline in jobs, wages and state tax revenues.

Occupy Lexington is trying to address these economic concerns through the “Invest in Kentucky” campaign, which is the brainchild of Ian Epperson, founder and director of the Lexington Sustainability Fund, which helps low-income families cut down on home energy bills. Standing in front of Lexington’s sliver of an occupation on a downtown sidewalk adjacent to a Chase bank branch, Epperson says he initiated the campaign to push government officials to “move Kentucky’s [public funds] of $12- to $15 billion into a financial institution that’s headquartered in Kentucky.”

A few months ago Kentucky transferred its general funds to JPMorgan Chase. Invest in Kentucky blasts Chase for a “disgraceful record” that includes wrongly foreclosing on active service members’ homes; issuing $33 billion in deceptively marketed mortgage-backed securities; “paying extravagant bonuses to top executives” after the bank was bailed out; and originating $30 billion “in subprime loans in the lead-up to the financial collapse.”

Epperson argues that transferring the money to a bank headquartered in Kentucky will create well-paying jobs in the financial sector and stimulate economic activity by making loans available to “entrepreneurs and small businesses, allowing people to build homes, creating demand in the construction industry, which has been hit hard in the recession.”

Supporting the local economy has won support from many backers of Occupy Lexington as well as nearby Occupy Louisville, which has endorsed the Invest in Kentucky campaign. Michelle Millette notes Occupy Austin has a similar focus: “A lot of people are talking about keeping money locally and shopping locally.”

There are limits to voting with one’s dollars, however, when 400 individual Americans have more wealth than the bottom 60 percent of the population – 180 million people – combined. Try outspending Bill Gates who has $59 billion or Charles and David Koch’s combined $50 billion. But at least occupiers are trying to identify paths out of the economic crisis.

Kentucky’s horse-racing industry is going the other way, betting that casinos will solve its woes, as many other state horse-racing industries are already attempting. It is part of a more disturbing trend.

Predatory capitalism follows the failed service economy. Across America there appears to be a direct relation between the casino economy and poverty. Depressed economies from Detroit and upstate New York to Mississippi and Washington have turned to some form of state-sanctioned gambling, which now exists in 41 states. It’s no accident that as inequality began widening in the 1970s, states turned first to lotteries and then to video poker, gaming rooms and full-fledged casinos in the following years.

The numerous gambling ecosystems we have passed attract kindred species: pawn shops, check cashing and payday advance outfits, liquor stores, strip clubs and giant billboards for ambulance-chasing lawyers. Personal vices are one thing; to turn them into a source of profit and government revenue is another. It means preying on millions of addicts and the desperation of the indigent.

And it means increasing the type of desperation and deprivation exposed by occupations across the country. The Occupy movement has served a valuable function by gathering together the poor and those on the edge to show how poverty results from corporate-created government policies that enrich the wealthy at the expense of the rest of society. Given the still-deteriorating economy and reverse-Robin Hood policies, however, it appears the ranks of poor and near poor will only increase.

Shares