On the spectrum of extreme literature, Dennis Cooper lies somewhere between the Marquis de Sade and the Old Testament. His novels – terse, scatological and violent -- are rooted in a kind of apocalyptic morality easily mistaken for sadism. The typical protagonist is a young gay man drifting from one trauma to the next, automatic and emotionally dazed. Cooper’s Southern California interiors take on the gothic ambience of bondage sets, autopsy rooms and theaters of the dark suburban absurd. In the hands of a lesser writer, such subterranean states would be merely lurid. Cooper, however, achieves something close to grace. Novels like "Try" and "Guide," part of a five-book series called the George Miles Cycle, are often unexpectedly tender. In chronicling his characters’ obsessive search for love, he confronts our most desperate human instinct.

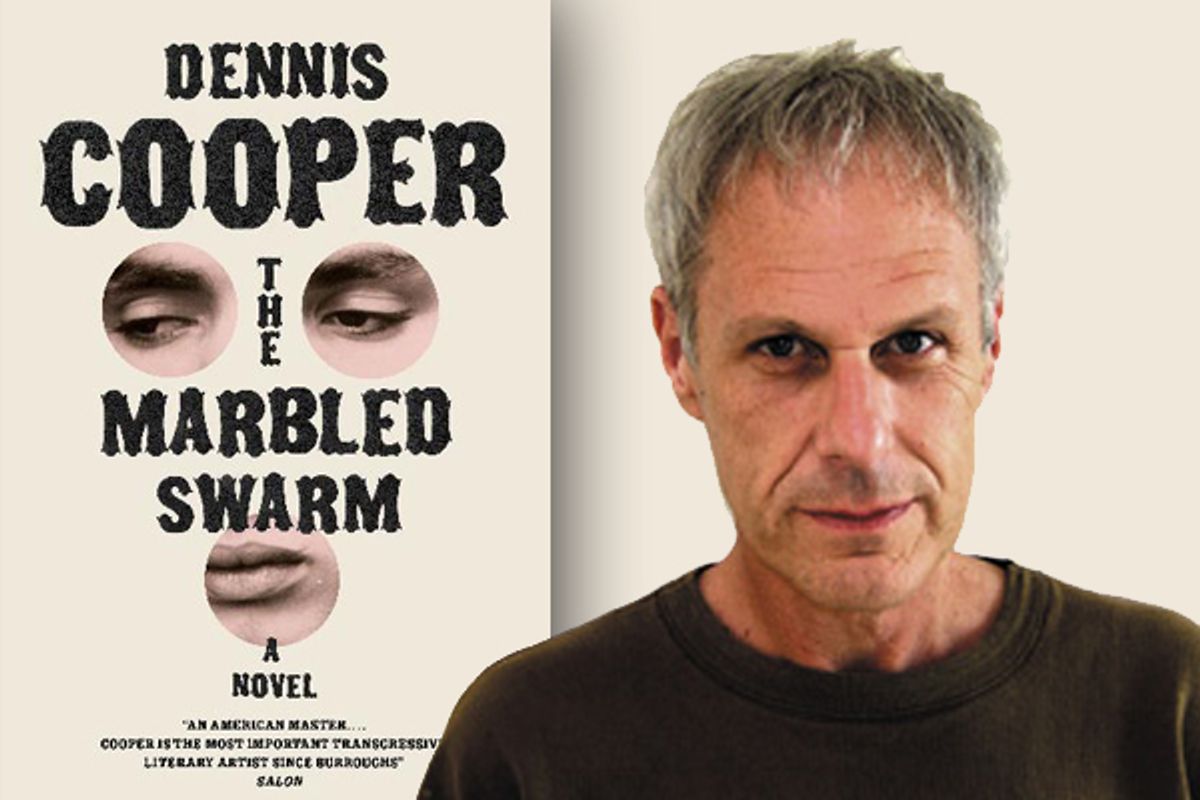

His new novel, "The Marbled Swarm," is something of a departure. Written in hothouse prose – one part Robbe-Grillet, one part Lautréamont – it’s the confessions of an anonymous 22-year-old Parisian. At the heart of the novel is Chateau Étage, a rural French manor scarred by peepholes, secret tunnels and a mysterious parricide. The house is a symbolic touchstone for the novel’s abundant doppelgangers, cannibals and sadomasochists, all of whom mirror and fracture as the narrative grows ever more precarious. It’s a vertiginous read, more hallucinatory than just about anything else in contemporary American fiction.

I recently sat down with Cooper on the San Francisco leg of his national book tour. Despite repeatedly emphasizing his inarticulateness, he proved witty and deeply focused. Over coffee in a North Beach cafe, we discussed pornography, fetishism, his incendiary blog and why Google will never take the romance out of discovery.

Do you think of yourself as belonging to a transgressive tradition?

No. Only because I always get drawn into that. Some of my favorite writers when I was young would be considered transgressive, but I like stuff that isn’t transgressive at all, too.

A few critics have noted a fairy-tale influence in "The Marbled Swarm." Is that something you were thinking about?

Only in the sense I was thinking a lot about Disney.

That's probably not the most obvious Dennis Cooper influence that jumps to mind.

I'm interested in how Disney flattens fairy tales. Disneyland just fascinates me. I grew up in Disneyland, went there a few times a year every year, so it’s in my blood. I still think it’s the happiest place on earth.

But the stuff in the book comes more out of video games. Zelda is the kind of game I’ve always loved and played. It's kind of like a modern fairy tale. I mean, it has animal protagonists [laughs].

Peepholes, and holes in general, are a recurring motif in this book. Tell me about your interest in voyeurism.

It’s weird. I’m not a voyeur actually. Well, I don’t know ... does looking at porn make you a voyeur?

Yes, to some extent.

Because I look at a lot of porn. So maybe in that sense, yeah, I'm a voyeur. I’m interested in the relationship between the reader and the writer, and there’s a kind of power imbalance there that's essentially voyeurism. In this book I explicitly go into that.

Has the role of the voyeur changed given the Internet?

There’s a big difference between that and a guy who peeks through his curtains at his neighbor taking a shower.

What about cruising? It seems like such an anachronism now.

The cool thing about cruising is you get the whole scale of a person. If you just see someone online you don’t really have a 3-D picture of them, so when you actually meet there’s a period of adjustment where they’re three-dimensional and you have to learn how their faces move when they talk. It’s very disorienting. There are also just fewer places to cruise now. In Paris it used to happen everywhere. I live right next to a place that was apparently a big cruising spot, but it's gone now. There’s just a little bit of illegal immigrant stuff going on. There are still bathhouses and saunas and shit.

Speaking of Paris, you live there but don't speak French that well. How has being estranged from the language around you influenced your own prose?

My friends over there speak English, but I’m always mediating what I say because I know they don’t speak the language very well. I think maybe I have a desire to be incredibly articulate. Like, over-articulate everything. And in this book, I wanted to do this thing where you have to wade through the bushes of language to figure out what people are trying to say. I don’t get to employ English in Paris as fully or unreservedly as I do here, so that made me want to really ratchet it up in the book.

There are characters in this book who fantasize about being run over by steamrollers.

Yeah, the Flatsos. It’s based on a real thing.

There are actual Flatsos?

There are enclaves of people who are obsessed with perverse forms of anime or manga. There's one called guro, which is mentioned in the book, and then all these sub-groups that enjoy violent pornographic manga. There's a group called squish junkies, and they incessantly draw pictures of themselves or movie stars being steamrolled. Or them having sex with pieces of paper, but the paper will be screaming. But no, there are no actual Flatsos. I mean, you can’t really make your face like a plate [laughs].

What’s the most extreme fetish you know of?

Worming.

Worming?

It’s basically you cut off your arms and legs so you’re just a trunk and a head, and you live like a worm. A master takes care of his slave worm.

Nobody actually goes through with this, right?

I don’t think so. What master would want to ... I mean, there’d be shit all over the place.

You've been charged with glorifying sexual abuse and pedophilia. All of the disturbing things that interest you are often dismissed as being merely numbing.

It’s not numbing at all. That’s the weird thing I’ve had to deal with. I can do all the nuances I want and critics just aren't going to see it. I’ve tried everything, every sort of strategy to circumvent that and have people realize it’s not numbing. It’s the opposite of numbing. It’s against numbing.

Does your family read your books?

No. My dad tried, he was really supportive, but my mom was just embarrassed by them. She was horrified when there were reviews in the L.A. Times because she thought her friends would read them and think she was a bad mother.

Which reminds me, I want to return to your interest in porn because it's something you write about so often. Every high school kid in America has probably watched porn online, and if they haven't they could very easily. Are you at all nostalgic for the days when pornography seemed more illicit or dangerous?

It’s interesting what happened to porn films. Porn from the '70s had all these narratives that are impossible to watch now. You’re just fast forwarding all the time because they have these complicated stories with real characters who cry and stuff. They’ll be maybe three sex scenes. And that’s because you were trapped. You had to sit in the porno theater and watch. Now you just don’t want people looking at your desktop; that’s the only thing illicit about it.

Were pornos more artful before the Internet?

Well, they aspired to art but very few of them were ever artful. There was this guy, Wakefield Poole, who did these Fellini-esque ones, and there was Jason Sato, who did Douglas Sirk-ean porn. They were like auteurs. They weren’t very good, but they were kind of interesting. I’m really into Eastern European porn because it’s very strange and bleak. There's an unintentional gravity to some of that stuff that can be disturbing. I mean, watch porn from Romania or Bulgaria or Russia and you can see they’re all prostitutes and doing it because they have to. You get much more feeling out of it ... more worry and conflict. You can’t look at these uncomfortable kids and not wonder what the story is there. It’s not art, but it can have the power of art.

You quit college to travel and gather experiences for writing. Is it still possible for young artists to re-create that kind of random, improvised journey in the age of information overload?

There’s the possibility, but the problem is the Internet is too important. To remove that would be to remove something that’s essential about the way life is structured now and the way our interests are dictated. The concern would be that you’d end up writing something parochial.

But it seems the mythology of the open road and that kind of haphazard, word-of-mouth itinerary doesn't happen much anymore. Everything is on Google.

But that doesn't take the glamour or poetry out of it. Reading about something and seeing it is so completely different. I don’t believe the whole idea people my age often have that everything has been lost because information is available. Art and music and writing are just as exciting now as they ever were. People are just as interesting. I don’t see us becoming less interesting because we surf the Internet. I think that’s old people being freaked out.

Shares