The revolution will be pixelated. It will be digital, yes, but also lo-fi and open-ended. And it's underway right now in the virtual world of "Minecraft," the deceptively simple online video game that has conquered the gaming world by stealth. Well, it was stealthy until one November weekend, when 5,000 die-hard fans converged on Las Vegas for Minecon and the celebration of "Minecraft’s" official launch.

“Launch” is a bit of a misnomer, as the game already has 16 million registered users in its beta form. The day before the announced launch, Mojang, the small Swedish company that created "Minecraft," quietly released its new smartphone app -- and within 24 hours it became the No. 1 selling app in the U.S. With an Xbox version of the game coming this spring, another 30 million Xbox Live subscribers will be jumping into the "Minecraft" Nether. The Minecraft Generation has officially begun.

As "Minecraft" is a user-driven experience, the convention's organizers decided to let the fans decide where to hold Minecon. Vegas must have sounded good on paper, but the heart of empty consumerism was a strange place to drop 5,000 Utopian-minded geeks. Each day there was a long, pasty parade through Mandalay Bay’s casino en route to the conventional halls; bleary-eyed gamblers and prostitutes didn't know exactly what to make of gamers in costumes and capes. At one point, a popular panel let out and Minecon enthusiasts found themselves outside a theater where Katy Perry was about to play. The anti-consumerist virtual army marched past a hyper-sexualized horde of sparkly-eye-shadowed tweens.

So what the hell is "Minecraft"? And what brought together these 5,000 die-hard fans from 23 countries? What’s difficult to explain to those who haven’t spent time with "Minecraft" is that it is not simply a game, but an open-ended virtual world, one that has spawned a massive and rapidly expanding online community. The gamers believe that "Minecraft" is a powerful force for creativity in an overly prescribed world. I went to Minecon with my guide and translator, namely my son, just shy of 13 years old, a "Minecraft" early adopter and veteran who has taught himself programming simply to manipulate the game.

But despite making Time magazine’s Top 50 Inventions of the Year, "Minecraft" has spread mainly by word of mouth and social media. I was the only journalist at Minecon who didn't work for a blog or gaming magazine. It's especially popular on YouTube, which has seen an explosion of screen-capture videos with voice-overs produced by “commentators” who do everything from show off their latest massive builds, “walk-throughs” of challenges and humorous send-ups of things like "Lord of the Rings" within "Minecraft."

Unlike the all-time bestselling online game, "World of Warcraft," you play "Minecraft" as yourself, not as a fantastic version of oneself. Therefore, when interacting with other players, you are interacting with humans, not someone acting out their fantasy of being a muscle-bound warrior with flowing locks, or a bosomy blood elf, or a 7-foot-tall slathering goblin. This lack of artifice makes for genuine, personal bonds and it was great to watch as people who’d known each other virtually for months (if my kid is any indicator) meet in person.

It was also interesting to hear parents of kids with Asperger's relate how "Minecraft" has enabled their kids to socialize in a way they never could before in the real world. Even more surprisingly, the kids have been able to translate these newfound skills into the physical world. One mother said that because her kid, who was brilliant but had trouble in school, spent so much time explaining aspects of "Minecraft" to his mother, he was able to translate this patience and work on his homework from start to finish for the first time.

- - - - - - - - - -

So how popular is this game? Many of the most popular commentators have become massive game-world celebrities and are now employed by the gaming video company Machinima (which boasts the most-viewed entertainment channel on YouTube, with nearly 950 million videos posted to date). The Machinima “Directors” make long, elaborate videos, often featuring electronic dance music soundtracks by artists like DeadMau5 and Skrillex. The most popular commentators, the Yogscast, are beyond even Machinima. Starring Simon and Lewis, a very funny British duo (who have a running shtick of their avatars bumbling through adventure maps), Yogscast now has over a million subscribers, and employs four people to keep up with the relentless demands of fans. At Minecon, Simon and Lewis were the elusive prey. Fans lined up for three hours or more for an autograph, and their presentation was easily the most well-attended panel of the weekend.

The game itself is an eight-bit, super-pixelated Java-built universe where you are a generic character (“Steve,” which you can personalize with your own skin) armed with nothing but a pickax. That’s it. Just Steve and the pickax. There are no instructions. It falls to the players to make the most of the randomly generated pixelated landscapes, which naturally involves, you guessed it, mining. You dig for various elements — from gravel to gold to obsidian — then combine (“craft”) elements into mine carts, tracks, doors, windows, and then build anything you want above- or below ground, including towers, Taj Mahals or music-generating trip-wires powered by intricate “redstone” circuitry.

The constructions can be truly spectacular. Sky towers of remarkable complexity, beautifully elegant, geometric, massive structures resembling cathedrals or Miasaki-like flying fortresses. Engineering marvels of circuitry that create whimsical “pig slot machines” or even other games within the game. "Minecraft" gives you the tools, and almost all players love to MacGyver more than anything.

Whereas "World of Warcraft" has set missions that you must complete to advance, the genius of "Minecraft" lies in its mutability and adaptability. Its creator, the Swedish game designer Marcus Persson, aka Notch, encourages outside coders to modify and subvert the game. This includes developing “mods,” which can be inserted into "Minecraft," introducing everything from werewolves to nuclear power.

"Minecraft" can be played in single-player mode, allowing for uninterrupted construction, or in multi-player mode with a running chat feature. Collaborative spirit is one of "Minecraft’s" main emotional engines. The game is played on a seemingly endless number of servers, both public and private, which you can then open to friends, virtual or otherwise.

"Minecraft" is revolutionary because it has no real goals, no real end. At least until Minecon, where Notch decided to announce “The End.” Notch, a self-effacing, charming, gnomish Swede in his ubiquitous fedora and polo shirt, told me, “I always imagined 'Minecraft' would have an end. I like games with an end. But,” he smiles amiably, “I’m not taking it too seriously.”

And neither did the gamers. Most were willing to indulge Notch his end. As it turns out, after playing “The End,” which involves defeating an “Enderdragon,” a menacing black dragon, which, in Classic mode took the assembled geeks anywhere from one to 15 minutes to dispatch, the gamers jumped right back into the heart of the game. For "Minecraft" users, it is all about the journey, not the destination.

After test-driving the new version on any of the hundreds of free computers set up in the exhibit hall, most gamers returned to creating their own worlds -- and to the all-consuming mission at Minecon: meeting the rock stars of their universe, the Directors. There was also buzz about who was actually going to get into the closing party, where wildly successful 23-year-old British artist DeadMau5 himself, a "Minecraft" über-fan, with a Creeper (the green, phallic, zombie-like creatures that prowl the "Minecraft" night) tattoo on his arm and a green Space Invader on his neck, would be playing.

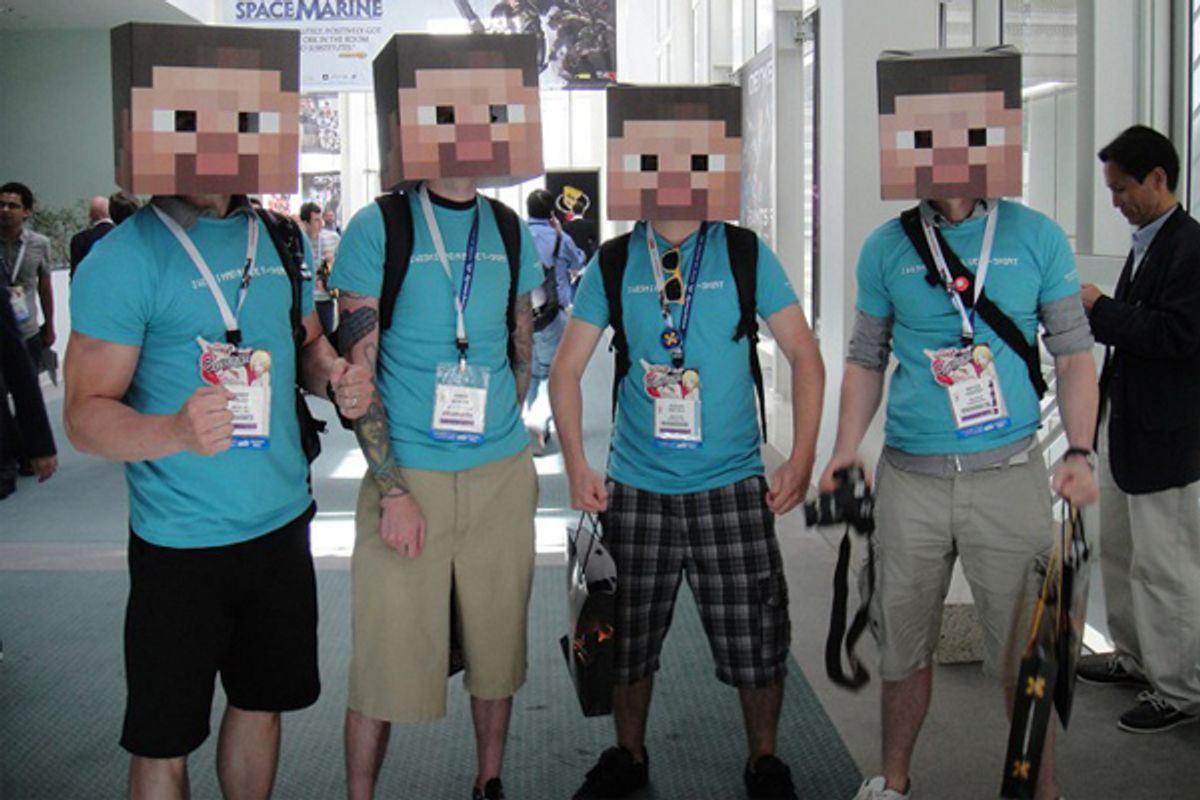

As with any geeky gathering, part of the joy is getting to be with your own people and letting your freak flag fly. In that spirit, many participants brought homemade pickaxes, diamond swords, boxheads and full-on costumes. The chaotic costume contest, judged by fan applause, was a highlight. There were plenty of Steves, Creepers, black-clad Endermen, boxes of TNT and even the online avatar of DeadMau5 — a blue mouse-head with beady red eyes. Since the crowd was half teenage boys, a “Sexy Wolf,” wearing only a few strips of fur, won going away.

- - - - - - - - - -

But this online world has applications in real life as well. On one panel, a Swedish developer discussed using "Minecraft" to redesign and rebuild dilapidated public housing. He said that the "Minecraft" rendering was much more user-friendly for the community, making it easier to envision the functionality of the new buildings and parks. The physical results exceeded everyone’s expectations.

Jason Levin, aka “the Minecraft Teacher,” founded MinecraftEdu and uses the game in his curriculum. He's discovered that students go beyond their assignments when "Minecraft" is introduced to the classroom. The game's applications range from simple ones -- foreign-language classes where students build a world and label everything with their new vocabulary words -- to elaborate. Students have made entire cell structures, or created the equivalent of a living, breathing book report of the "Lord of the Flies" island, re-created with all of its characters. “If the kids are already going to be playing 'Minecraft,' why not incorporate these challenges?” he said.

Collective, virtual problem-solving that can be applied to the physical world is most certainly the future. Game theorist Jane McGonical, author of "Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World," is convinced that an entire new generation raised playing collaborative games will help solve the world’s greatest challenges. In online games, she argues, we are at our best and most optimistic selves. Real-world goals of money, fame and beauty are more and more hollow to young people, she suggests. They're much happier collaborating on “epic wins” in the virtual world. She believes that we are well on our way to harnessing this energy and creativity to tackle real-world issues.

It's an argument that dovetails with Rachel Botsman’s economic utopian theories. Botsman, the author of "What's Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption," argues that we are moving away from endless consumerism. Economic necessity and finite resources, she writes, have generated a moral shift; many people are now more interested in “uses versus possessions.”

At Minecon, this utopian idealism was pervasive. The participants ranged in age from 4 to 77, and there were many, many families present, usually one parent with one very happy teenager. A majority of the parents were players themselves, while a sizable number came to find out more about this all-consuming passion. Via Twitter, I noticed that Lauren Myracle was in the building with her 13-year-old son, who is only a few months older than mine. Myracle, who had been disnominated for the National Book Awards YA category in a colossal blunder on the part of the NBA, decided to attend Minecon rather than accept an invitation to the awards ceremony. When we spoke, our sons talked about which Directors they had met, and we tried not to embarrass ourselves in front of our kids as we compared notes about the phenomenon. Like most of the parents at Minecon, we found that we are much more willing to indulge endless hours of "Minecraft" as opposed to first-person shooter or role-playing games.

I also tracked down Alex Leavitt, who is working on his Ph.D. at the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Southern California. His thesis is on "Minecraft" and its popularity. (I studied the psychology of sport in grad school, so I know the incredulous eyebrows Alex gets.) Leavitt is onto something quite profound. As an academic subject, "Minecraft" is endlessly fascinating, and changing by the second. “Two years ago this couldn’t have happened,” Leavitt told me. “The infrastructure was not there to support this.” Leavitt told me that one year ago there were a few thousand "Minecraft" YouTube videos. Today, there are well over a million. And with the rise and cult of the Directors, these videos are heavily curated with instantaneous feedback. “Captain Sparklez,” one of the most prominent Directors (his “Revenge” video, based on the Usher song “DJ’s Got Us Fallin’ in Love,” about the dangers of Creepers, is a "Minecraft" legend with over 16 million YouTube views) says that within minutes of posting a video he has thousands of comments. “You are my content,” he told a cheering crowd of fans.

Minecraft Miles, who has the daunting task of running the constantly updated Official Minecraft Wiki and Forum, came to Minecon straight from Occupy Portland. He was very happy to have his first shower in two weeks. You might think that a populace that spends a lot of time in a Lego-like virtual world wouldn’t be in tune with current events, but the Occupy movement was very much in the Minecon air. Everyone who works for the tech company IGN, the official online streamers of the convention, were wearing “Occupy Minecon” T-shirts, and there was more than one overheard conversation along the lines of “How do we take Occupy into 'Minecraft'?”

For all the utopian, anti-consumeristic idealism, the most popular booth at Minecon was Jinx, the official swag retailer, which had a nonstop line for T-shirts. There’s nothing like a physical manifestation to show which tribe you belong to.

Indeed, Minecon attendees left with a new sense of how profoundly meaningful the community is to so many players. With the new app and the Xbox versions, the "Minecraft" revolution is only going to spread further and deeper. While I’m looking forward to all of the incredible new "Minecraft" creations, what I’m particularly interested in is what the Minecraft Generation is going to do in the virtual and real worlds. My son and several million other kids are coming of age playing a utopian game with no limits and no rules. Their creations are going to change the world in ways we cannot imagine.

Shares