How did the end of the Cold War change the modern spy novel? Why is it that Cold War tales still seem to resonate so deeply with international audiences? How is our sense of who our enemy is reflected in contemporary spy fiction?

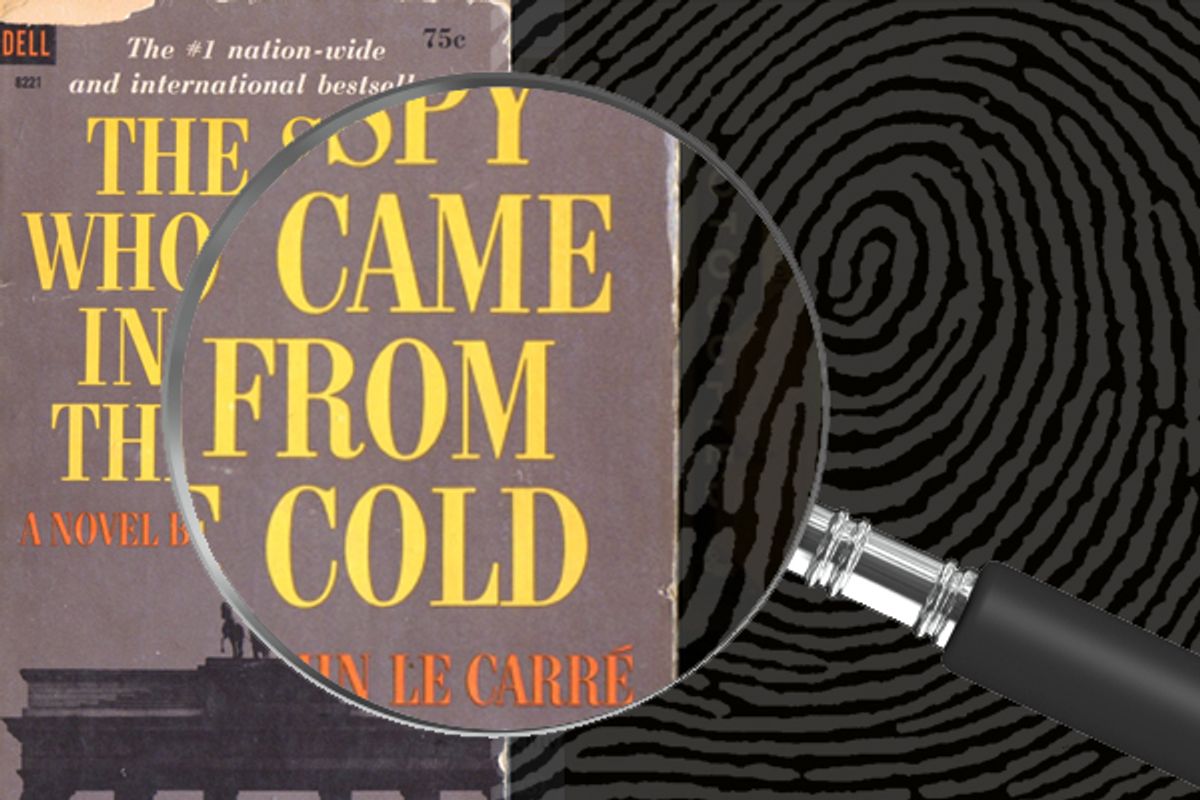

As "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy," based on the classic John le Carré novel, hits theaters today, Salon asked a round table of bestselling thriller writers, intelligence specialists and historians to share their thoughts.

We want to know what you think, too. Post your thoughts about the future of spy stories in our Comments section, or blog it on Open Salon (tag it: FutureSpy) and we'll add the best thinking to the list below.

Jeffery Deaver, bestselling thriller writer and author of "Carte Blanche"

I don't see much of a change [since the end of the Cold War], frankly. The crux of good espionage fiction has always been micro: a compelling story of one or two individuals up against an enemy. The ideology of the bad guys and whether or not they are state- or non-state actors are to me irrelevant. A good spy story draws us into a small but compelling world filled with overwhelming threats, duplicity, moral questions and heroism. A competent author can do this regardless of the allegiance of his antagonist. Look, for instance, at John le Carré's novels of the post-Cold War period ("The Night Manager," for instance, about drugs and arms), Ian Fleming's James Bond thrillers in the '50s and '60s, during the height of that era, or one of Graham Greene's pre-Cold War spy novels, like "Ministry of Fear."

The most significant distinction in the post-Cold War era is coincidental: the rise of technology. Much of today's espionage is SIGINT and related intelligence gathering, with the bulk of a spy's job being conducted electronically from high-tech locations in suburban Colorado and Maryland. Ah, for the good old days: spying on your nemesis while sipping pastis in a Parisian cafe, with your fedora pulled down and your trench coat collar pulled up.

Eric Van Lustbader, bestselling author of "The Bourne Dominion" and "Blood Trust"

First, you have to ask how the Cold War affected the spy novel. In those days, many of the spy fiction writers had served in World War II; others, like Ian Fleming, were actually in the secret service. Those who weren’t directly linked to the clandestine services, like Bob Ludlum, developed many contacts within them.

Second, Cold War tales resonate so deeply because in the past we had one monolithic, brutal regime, accurately named the Evil Empire. During the Cold War, international politics was relatively simple: it was Us versus the Soviet Union. One on one. Capitalism versus Communism. Easy to understand and to write about.

The end of the Cold War, the demise of the Soviet Union, came about in a totally surprising manner. It wasn’t a series of military or political victories on our part that brought it about: it was an economic collapse. The Soviet Union had simply grown too big for Moscow to keep control over its sprawling expanse. I’m quite certain there wasn’t a single spy fiction writer in the Cold War era who had foreseen this conclusion.

But there was another, more subtle reason for the Soviet Union’s breakup, and that was religion. The Kremlin had been largely successful in snuffing out the influence of Catholicism and Judaism among its population, but it had had much less success in repressing the various, more numerous Muslims in the far-flung countries under its control.

The end of the Cold War brought a relatively short period of what can only be termed “international calm.” Sadly, this was short-lived. The enemies of the West, not merely capitalism, were now many, many splintered cells, operating all over the world. There was no central hub, no unifying concept, except death to Infidels. The rise of radical Islam has been breathtakingly swift and undoubtedly frightening to many. Islam is not well understood in the West. It is, therefore, all too easy to look upon every Islamic as a radical, an enemy. Islam is a religion of peace. But, as with any religion, there are fringe elements – vocally and demonstrably rageful – who turn religious principles to their own violent ends. Abject poverty and ignorance are massive contributors to the rise of Islamic terrorism.

Demonization of the Other has always played a major role in spy fiction. It was easy when writing about the KGB, but in today’s fractured international climate the ability to set the right tone and achieve a proper balance between good and evil is becoming ever more complex, ever more difficult.

R. J. Hillhouse, intelligence analyst, blogger and author of spy novels

The end of the Cold War set both the spy novelist and real spies adrift in search of new enemies. Both novelists and the real-life intelligence officers they portray struggled to come to terms with the new international playing field without such a clear-cut enemy. The reaction of most spy novelists was to ignore politics and move on to less weighty affairs.

Sept. 11 brought order to the fictional world of spies just as it did to their role models. Terrorists became the enemy; the multibillion-dollar military, intelligence and homeland-security industries aligned themselves behind this paradigm. One by one spy novelists returned to politics and jumped on board with one-dimensional terrorists as the new bad guys and gave cultural credence to the new boogeyman. The spy novel has found itself back in a similar position as in the early decades of the Cold War when the Soviets were evil and morality was an American monopoly. The few notable exceptions included my own "Outsourced," which took a critical look at the murky world of the multibillion-dollar private intelligence and military industries.

As the Cold War dragged on, the spy novel matured and began to take a more critical examination of who we were because of the enemy and our response to him. We can hope that spy novelists tire of the War on Terror narrative and the post-9/11 spy novel has a similar coming of age.

Robert Baer, former intelligence analyst and author

Who thought that the fall of the Berlin Wall would also take the air out of spy fiction. Frankly, I find the current stuff unreadable -- wheel kicking Islamic terrorists, defusing at the last minute a bomb that's about to take down civilization as we know it. The stuff belongs either in the comics or war novels. In any case, no one's going to top Forsyth's "Day of the Jackal" for tick-tock drama. I think that's why we miss Cold War espionage fiction, its subtlety and three-dimensional characters. For my money, the classic espionage novel is le Carré's "Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy." The writing's good, but what makes it great is the brilliant, believable enemy, Karla, the KGB master spy. And he's not a stretch -- the KGB really was that good. In fact, I'd say most of the time they were better than both us and the British. Outwitting the KGB, catching Karla mole inside MI6, is the stuff of drama. And let's not forget the Soviet Union truly was an existential threat -- unlike Bin Laden.

The other day I heard the CIA has had to resurrect some old Moscow hands, operatives who'd spent their careers working against the KGB. It was in reaction to a recent CIA compromise in Beirut in which the Islamic militant group Hezbollah outwitted the CIA. The CIA apparently has to relearn spycraft. So maybe the espionage novel is on its way back.

Gayle Lynds, bestselling spy novelist

All governments lie. All spies lie. They’re supposed to. But that doesn’t make it right; on the other hand, sometimes it does. All novelists lie, too, but we call it fiction. This is a natural alignment that sold hundreds of millions of espionage thrillers during the Cold War.

Then the Iron Curtain crashed. As New York Times critic Walter Goodman announced funereally in November 1989, the same month the Berlin Wall crumbled: “The future looks dismal for the trenchcoat set.”

He was right. The field with its big, exciting books of Cold Warriors facing off against agents of the Evil Empire was about to be liquidated, eliminated, scrubbed.

The espionage sea change began almost immediately. Exhausted by paying attention to the world at large, Americans cocooned. In this shadowy lull, we liked to think we were at peace and, as the last standing superpower, untouchable. Overseas press coverage plummeted. International reporters and photojournalists couldn’t find jobs. At the same time New York publishers warned editors not to buy new spy fiction because the field was as dead as the Cold War.

Of course publishers continued to bring out spy thrillers by box-office names like Robert Ludlum and Tom Clancy, but their sales plummeted. By 1998 thriller icons Frederick Forsyth and John le Carré had declared it was time to accept reality: The black business of international espionage no longer interested readers. Both men fled to fresh literary turf.

Still, many of the stars who stayed tried to reinvigorate the field. I remember one editor telling me Ludlum was in trouble because his numbers were circling the toilet, so he was going to do something daring — write a female villain. The result was "Scorpio Illusion," published in 1993, a New York Times bestseller. Other authors introduced female lead protagonists. Taking a different tack, still others wrote female heroes, female villains, and set their novels in the past, not only during the Cold War but also frequently during World War II, which seemed a safer bet.

Little helped — until 9/11. That was the spy game changer. Applications to the CIA soared, and so did the demand for international journalists. Any American who spoke Arabic or Farsi could get a job. The horrific events of 9/11 had shown us we could no longer afford to ignore the world at large. Definitely we needed to know more about it. In fact, it was interesting.

We are a nation of readers, so of course we turned to books. One of our favored resources for information has long been through the lens of quality political fiction, such as the best espionage novels.

9/11 birthed the modern spy novel. Assassins became antiheroes. Females abounded in both heroic and villainous roles. Without the old Soviet Union to narrow our focus, novels grew wide-ranging and rich — examining not only al-Qaeda and terrorism, but also merchants of death plying the gray market arms trade, intelligence community links to corporate espionage, the legality and role of government contractors, worldwide interrogation practices as a form of warfare, technological advances that can both aid or hinder, disagreements within the international spy community that lead to willful mistakes, the effect of White House policy in shaping intelligence analysis, espionage as a source of not only power but revenge.

Readers responded. By 2003, the “espionage/thriller” novel category had leaped a whopping 34 percent in sales, according to PW Newsline. And Le Carré and Forsyth rejoined the field with very contemporary spy stories. But then there’s so much to write about, so many enemies to explore, and what better field than the international spy thriller, proving again what J. Edgar Hoover said many years ago: “There’s something about a secret that’s addicting.”

Tom Nichols, professor of national security affairs at the United States Naval War College

The end of the Cold War killed off the modern spy novel. Purists will object, and say that the greatness of the spy novel lies not in politics, but in character studies, especially of flawed people in toxic moral circumstances. Even James Bond once referred to spying as just a game of “Red Indians,” and he has to be sent at one point to Jamaica to prevent him from having a nervous breakdown.

The problem is that for the spy to live such a high-voltage life, something grand and terrible must be at stake. Like, say, World War III, or even Civilization As We Know It. And without the Soviet Union (or Nazi Germany before it) and the struggle with a titanic power, there’s really not much to the genre. The kind of novel where the world itself hangs in the balance, where moral choices are stark because they are moral choices -- that’s gone now, for three main reasons.

First, suspense novels are now generic. A beautiful journalist meets a tormented spy, and together they unravel a plot that will go all the way to the Oval Office and shake the world to ... well, you get the idea. The plot is never really all that world-shaking, and the Oval Office is usually just a nest of creeps and nincompoops.

Second, they’re cynical. Nothing is ever as it seems, because no one really cares about anything anyway, and when they do, it’s usually the wrong things, like how much all governments really stink. (However, there has since been a recent trend of perfectly awful right-wing spy novels where the hero is always a military officer or military reservist, but out of respect for both the military and literature, we’ll ignore them.)

Finally, and most importantly, the bad guys -- usually greedy businessmen or terrorists -- are now uninteresting. Terrorists are especially uninteresting, because for a spy novel to work, the agent needs a worthy adversary. A spy novel also has to include spying, not law enforcement. (Indeed, one of the worst barbs ever aimed at James Bond was Dr. No’s zinger that Bond is just a “stupid policeman.” Ouch.) ... Spies no longer engage their professional equals, but rather are like playground monitors in a field full of children with machine guns. There’s not a lot of suspense to be had if MI-6’s top agent is up against some nerd with a couple of arrests for soliciting hookers back in Southern California and is hiding in Yemen while advising other guys over the Internet on how to make bombs. (I don’t know if MI-6 still has any top agents, but that second guy is actually the late Anwar al-Awlaki.)

The Soviet and Nazi totalitarians, worthy and dangerous enemies both, are gone. Sadly, they took the great spy novels with them, but it’s a small price to pay.

Charles Cumming, British spy novelist and author of "The Trinity Six"

I’m not sure that [the end of the Cold War] did change the spy novel, per se; I think technology and greater freedom of information changed it. During the Cold War, there was no Internet, no mobile phones, very few security cameras on the streets, limited opportunities for travel behind the Iron Curtain, and only primitive satellite surveillance. At the same time the general public knew very little about how their intelligence services operated. They had to get their information from Clancy or le Carré or Spycatcher, all books which – for different reasons -- needed to be taken with a pinch of salt.

Nowadays, most people in London could point to the headquarters of MI5 and MI6. The Chiefs of both Services are public figures. Vast amounts of information about espionage – from tradecraft to budgetary cuts – is available online and in print. In other words, the mystique surrounding spying has been stripped away. That this has happened in the 20 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall is just a coincidence.

Why is it that Cold War tales still seem to resonate so deeply with international audiences? I think it’s a mixture of nostalgia for the period and a sense that the Cold War, for all of the misery that it wrought behind the Iron Curtain, was not a particularly dangerous or oppressive time for people in the West. Of course, Europeans and Americans lived with the theoretical threat of nuclear armageddon, but they were never attacked by the Soviet bloc. The tension between the two systems – Communist and Capitalist – was played out at the level of diplomacy and propaganda. What was the worst that could happen? The Soviets could try to stockpile missiles in Cuba. An old Etonian might turn out to be working for the KGB.

You can’t say that about the threat posed by radical Islam. In the last 15 years, al-Qaida has struck at the heart of cities in Europe, Africa and America and been responsible for the deaths of tens of thousands of people. In other words, there’s nothing playful or mysterious about what they’re up to; al-Qaida is a death cult which isn’t choosy about its victims. Furthermore, I think people are sick of reading about Iraq and Afghanistan. They would rather go back to the great playgrounds of the post-war era – Moscow, Berlin, London, Vienna – and to the reassuring certainties of East versus West. This is what I mean by nostalgia for the Cold War. It’s an aesthetic choice.

Olen Steinhauer, author of "The Tourist"

I’m not sure the end of the Cold War changed the spy novel in any significant way. What it did was take from espionage novelists the greatest and most dependable of enemies — but was the fight against Soviet communism really what Cold War spy fiction was about? The triumphalist stuff, maybe, but the better work used that conflict as an excuse to investigate the effects of betrayal and deception on the individual — and betrayal and deception haven’t gone away with the disappearance of Soviet communism.

Yet there’s no doubt that the texture of the Cold War provided great material for writers in the genre, and those stories touched readers deeply — arguably more deeply than most contemporary spy fiction. Why? For Western audiences, the “other” of Cold War fiction was recognizable. Those communist infiltrators looked like us, dressed like us, and held a fork the same way we do. These sound ridiculously surface, but they’re not, particularly when you add in a Marxist philosophy that most Westerners could understand and relate to, even if they disagreed with it. The chain-smoking agents who trailed our protagonists weren’t just believable; they could easily be sympathetic — we could see ourselves in them.

These days, the identity of the “enemy” feels so fragmented, as if the threat to the nation is from a million little cuts — financial, terroristic, sociological and military — rather than a single hard blow. The closest we have to a generally agreed-upon monolithic enemy is Islamic extremism, and there’s the rub: It’s hard to write a believable suicide bomber who isn’t just a dupe for a higher-ranking mastermind; and when a mastermind sends children off to blow themselves up, it’s hard to get an audience to empathize with his philosophy or his job troubles or his problematic love life. Not that this can’t be done — anything can be accomplished in fiction — but it’s a hell of a task. And without enemies that readers can feel for, espionage novels tend to just run in place, going through the motions.

Additionally, the truly great spy novels of the Cold War achieved their effect by stripping away our romantic notions about ourselves. Brilliant English public school boys with the world before them could become Soviet spies (Le Carré), and so could our wives (Deighton). Charles McCarry’s spy was a model of absolute morality — the intelligence world’s morality, which it turns out is in sharp contrast to what the rest of us think of as moral. The great works of espionage shocked us by revealing the terrors we were capable of and making them feel utterly believable.

By now, though, we already believe in the evil man can do to man — motivated by greed or simple incompetence — because journalism trumps fiction day after day, showing us how the sausage is made. Is there really anything that can surprise us anymore?

Which is another way of saying that today’s spy novelist has some real challenges, and each writer deals with this in his own way. The enemy in a contemporary spy novel may say less about the world as it is than it does about that particular writer, and his insecurities toward his craft — the enemies he avoids may be the ones he’s not sure he can write. It’s why suicide bombers and their masterminds haven’t made it into my own novels ... yet.

Shares