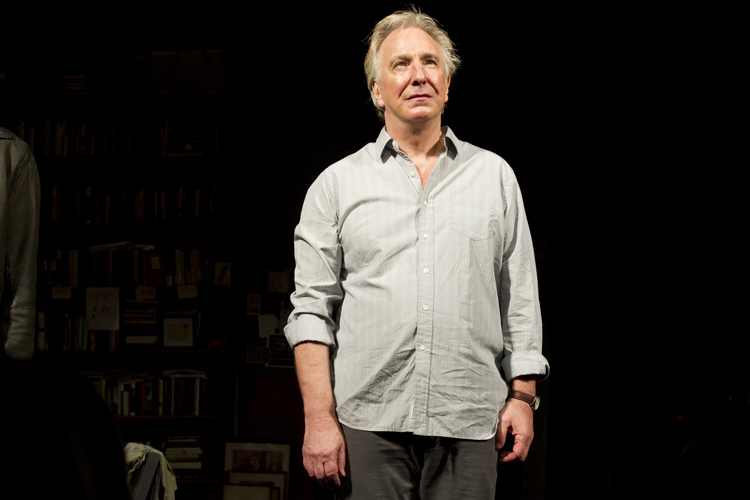

“Seminar,” a play starring Alan Rickman as a preening, acid-tongued teacher running roughshod over a group of tender aspiring writers, opened a few weeks ago on Broadway. Reviews have prompted all the usual observations about the difficulty of dramatizing both writing and reading, activities so internally momentous yet so physically inert. Why, then, do people keep doing it? And do the depictions of writing classes in stage, film and television — from “Wonder Boys” to “Bored to Death” — bear any relationship to real life?

To hash this out, I invited Ben Marcus — a novelist and an associate professor at Columbia University’s School of the Arts, where he teaches fiction writing — to see “Seminar” with me and talk afterward about the ways writing workshops are depicted in the performing arts. His first novel was acquired by the writer, editor and teacher Gordon Lish, considered to be the inspiration for the character played by Rickman, and Marcus also attended one of Lish’s legendary seminars, conducted in private homes, like the class in the play. (Marcus’ fourth book, the novel “The Flame Alphabet,” will be published in January.)

We found Theresa Rebeck’s play amusing and pointed — right down to a reference to the bi-coastal literary magazine Tin House — despite the fact that it doesn’t bear much resemblance to any writing class we’d ever encountered. That, we concluded, might be for the best.

When characters are discussing writing in a dramatic work like “Seminar,” the things they say are so sweeping compared to the more detailed focus of an actual writing class. But what also struck me in this play is how the concept of writing and of being a writer is so intensely romanticized.

Also, the students have no ability to determine their own value for themselves. That’s the great conceit the whole play is riding on, that these people can’t begin to make a decision for themselves. That makes them funny, silly and ultimately vulnerable.

I noticed some of that with Gordon Lish. There were degrees of vulnerability around him. On one hand, it was easy for some people to blame him for his forcefulness, but with people who weren’t quite as vulnerable, I think that they thrived and got a lot more out of it. They got to listen to him talk inside and out about a piece of writing and to see that he could be deeply perceptive and that he cared about fiction more than anything else in the world.

The people who got caught up in the theater of winning his approval instead of, say, deriving their own system of self-worth, they didn’t seem to fare so well.

Would you say that some of the people who went to his seminars were like the characters in this play? Like a lot of writing students in movies and TV, they seem to be in the class for the sole purpose of getting a verdict on their work from some big-time authority figure.

In the students, I didn’t really recognize anybody I’ve ever seen. There are little bits here and there, but the thing I really didn’t recognize is the sort of blatant and publicly articulated desperation. There’s one character, the one who’s using his connection to his famous uncle, who is a very enjoyable stereotype. But anyone who behaved that way in front of any writing student I know — people would be horrified by that. Most people are self-aware enough not to behave the way that guy does.

But even if people don’t behave that way that doesn’t necessarily mean …

… that they don’t think that way, no. You could argue that it’s the play’s job to externalize that stuff because it’s funnier to see everybody acting on their demons and their craven desires. It’s more entertaining.

There’s stuff that, as the teacher, you don’t necessarily see. I once taught this class, maybe five years ago. It just never gelled. There was something strange about it. I just thought that I sucked because I couldn’t get them going. The semester ended, and I ran into someone who’d been in the class. That person then told me about this elaborate set of dramas that was going on among the students. There was a broken love triangle, someone who tried to kill someone else and they hated each other. It was just insane! I had no idea. They were consumed by their own drama.

Speaking of drama, the play takes the position that writing is a completely tortured experience.

Tortured and joyless, with no possible good outcome for anyone. One of the funny things that Alan Rickman’s character does is that he gives these predictions about everyone else’s future: This is what your life will be, in these funny monologues. The most talented one, who was writing the best work, he’s got a miserable future ahead, totally miserable. There’s no redeeming thing about it at all!

He’s going to end up like the Alan Rickman character.

A big difference that I would cite from Gordon Lish, is that he didn’t have any of the buffoonery of the Rickman character. He wasn’t self-important or grandiose, with the bragging, the travel and the overt sexual stuff. I think there was clearly a big ego there, but he was also very modest in person. His feeling was, “I will never do really great work, but maybe you will. If you think about these things, maybe you will. It’s too late for me.” The drama was about whether or not you could get behind his enthusiasms.

The thing he did that might be construed as abusive was that he was interested in pitting people against each other. Let’s say we have Smith and Dale: Smith might write something interesting and Gordon would say, “Dale, what’s your answer to that? How are you going to sleep at night knowing that your buddy here has written something so good?”

I think the pedagogical idea is that you might work harder if you feel competitive with your peers. Sometimes he would create competitions, but other times the students just weren’t biting.

What the Alan Rickman character does — his long, irrelevant, self-glorifying digressions about his adventures in various kinds of disaster tourism — well, maybe Gordon Lish didn’t do that, but I’ve certainly heard about a lot of writing teachers who do.

It struck me as a more old-fashioned, first-wave creative-writing model. The famous writer is trucked into the Midwestern university. He’s drunk all the time and he makes these pronouncements. You don’t even get your work read, but you sit at his feet and listen to these drunken tales and that counts as some kind of instruction.

I got my MFA about 20 years ago, a little more. Then, there wasn’t much of an established tradition of actual instruction. Now, 20 years later, if there are 12 students in the class, the students are getting back 11 copies of a submitted work, plus the instructor’s, with intensive line editing and one-and-a-half to two-page, single-spaced typed criticism — more criticism on this apprentice work of fiction than you get when you publish a book. This feedback machine has been created, giving students some pretty substantive criticism. That, I think, takes the spotlight away from the instructor as this Svengali figure who makes these pronouncements that are going to lead to some shattering revelation.

Enjoyable as those revelations are to watch on stage! Another thing you don’t see in the play is the idea that there are different types of literary traditions, each equally valid, the idea that good writing can be something other than opening a vein on the page. One of the characters writes a fake memoir about a transvestite Cuban gang member that completely deceives them all until she tells them with great amusement that she’s the one who wrote it. They all think it’s fantastic before that, but it’s still presented as a debased thing for her to do.

Well, she’s taking a sort of superficial bait by going for this supposedly gritty, real-world authenticity that the teacher wants. There’s a little bit of satire in there, right, because she can actually ape this form perfectly and she makes a successful piece of writing. It says something about how we value the personal stories behind the writers. If it’s a book about the streets, we want the writer to be …

… of the streets.

Yeah. You see that when you’re promoting a book. No one’s interested in talking about the actual book. They want to talk about the person who wrote it. What bad things happened to you that we can talk about? So the play does some funny satire about our desire for the “real” by also showing that someone can fake it. It’s just a style. It’s artificial and anyone can do it.

Then there’s the figure of the young woman who writes a lot about sex, and she’s very pretty and fully prepared to capitalize on that, and this generates a lot of bogus interest in her work. Now, that’s not an unfamiliar kind of writer, but sometimes the writers who fit that profile are actually really good writers as well.

They are.

They’re more mediagenic, and many people resent them for that, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t be talented, too. In the play, that character is sympathetic, very grounded. But she’s also a slapdash person who isn’t committed to doing good work. She’s likable, but she’s supposed to be a contemptible writer.

She didn’t have any gravitas at all. But then gravitas is often an awful thing to encounter when you’re teaching. It doesn’t correlate to anything. When it’s attached to really poor work, it’s torture.

Each of the students had to play a certain type, right? They all play really well. There is the glib, competent, self-promotional one. And there’s the sullen genius who refuses to show his work to anyone — but that’s where it all starts to fall apart. He, in the end, is immune to the praise that he’s so covetous of.

It’s meant to show his integrity, I guess.

Yet he was still there, still soaking it all in.

He’s the character who dissents from the seminar and has a distance from it in a way that the audience shares. He’s a skeptic about everyone else’s shtick, recognizing it as shtick, which is what the audience is doing, too.

It’s funny to see these types, but it would have been funnier if their writing didn’t correspond to their type in such an obvious way. Because, too often, the self-important, brooding genius type — that guy is bad. He’s so bad.

Yes! In real life, the guy who is melodramatic and idealistic and angry about the importance of writing, and just so grandiose about it, is also the person who lacks the subtlety or wit or humor or perspective to be a really good writer.

There’s really the biggest myth of all that’s propagated by the play, which is that somebody’s persona has a lot to do with the quality of their writing. That’s just never true. Sometimes, it’s the dull, plain person who turns in totally killer, electrifying writing. Sometimes the really dynamic, witty, amazing person just dies on the page after the first sentence. Or, sometimes the really talented person is just a complete sweetheart. Just a really nice person. The whole notion of equating somebody’s personality with what they’re capable of creatively just falls apart very, very quickly.

One of the characters takes a job as a ghostwriter, and that’s treated as a fatal deal with the devil. Once you take a step in that direction, you are doomed as an Artist. She couldn’t possibly learn anything from it. That doesn’t take into account how Hemingway’s early work as a reporter affected his fiction, let alone the fact that a number of revered novelists — Don DeLillo, Peter Carey — started out working in advertising.

It’s really a portrait of a certain kind of idealism that you can only have before you’ve done anything. It’s of a certain age and a certain stage.

But if you’ve never gotten past that stage, or have only seen it from the outside, it might seem like the way all writers are. Which is why the play convinces its audience, perhaps.

Everybody was laughing.

Laughing in a very knowing way, too! I get the impression that the image many people have of writing classes comes from this sort of depiction.

What’s funny to me is that, as far as I know, instruction in some of the other art forms doesn’t seem as available for satire and derision. Why aren’t we making fun of people making mud sculptures and the pretensions of teaching in the visual arts world?

That’s especially puzzling because when it comes to visual arts, you can actually show the audience what the characters are making.

And, oh my God, it’s even worse. I’ve seen it firsthand. They say things that, if you wrote them down — there’s nothing there. The kind of faux theory shit that comes up is so crazy and meaningless. It should be made fun of so much more! And yet, we don’t treat the formal study of painting as if it were a joke. We don’t question that someone might want to go to art school.

Or music school.

Boy, that just seems like it would be the last subject for comedy, right? A music class in graduate school. And yet, when it comes to writing classes: “Ha, ha, ha! What morons! They think they can get together and talk about writing!”

What is that? There’s the whole “Writing can’t be taught” thing. I was once at a dinner, and at the other end of the table there was a gray eminence writer, whom I won’t name, who said, when asked if he taught, “Writing can’t be taught.” And I, a smartass 20-something, leaned over and said, “You mean you can’t teach it.” Because how does he know? That’s like me announcing, “Cello can’t be taught!” because I can’t teach it.

I think a lot of stuff does get taught and it can be talked about. I think writing is a craft. Language is the medium and you make things with it. But, you’re right. This play isn’t for people like me. It’s for people who have a vague idea about what goes on in a writing class. It’s a rough enough sketch, and it’s funny enough. It would be dour to demand realism from that play. It would be ridiculous. It would just take the entertainment away. I would never go to a play that was accurate about teaching. My God!