In the immensely enjoyable film "How to Make a Book With Steidl," of the cavalcade of famous artists seen developing books with Gerhard Steidl, photographer Joel Sternfeld serves as the unwitting costar. We watch Steidl jet around the world – a day with Robert Frank in New York, a quick trip to Paris for some face time with Karl Lagerfeld, a bonfire with Khalid Al-Thani in the Qatar desert, afternoons with Ed Ruscha in Los Angeles, Robert Adams in Astoria, Ore., Jeff Wall in Vancouver – and on-screen there are nothing but strong personalities, people with distinctive, uncompromising visions. But of all the projects we witness in various stages of production, Sternfeld’s book of iPhone photographs shot in Dubai, "iDubai," is the one book we see through from concept to completion.

In the immensely enjoyable film "How to Make a Book With Steidl," of the cavalcade of famous artists seen developing books with Gerhard Steidl, photographer Joel Sternfeld serves as the unwitting costar. We watch Steidl jet around the world – a day with Robert Frank in New York, a quick trip to Paris for some face time with Karl Lagerfeld, a bonfire with Khalid Al-Thani in the Qatar desert, afternoons with Ed Ruscha in Los Angeles, Robert Adams in Astoria, Ore., Jeff Wall in Vancouver – and on-screen there are nothing but strong personalities, people with distinctive, uncompromising visions. But of all the projects we witness in various stages of production, Sternfeld’s book of iPhone photographs shot in Dubai, "iDubai," is the one book we see through from concept to completion.

Notorious for commissioning projects that are often many years late, it seems a minor miracle that Sternfeld’s book came to fruition over the course of the film being made. Of course, Steidl would reject the accusation that his titles are “late,” because although he does sell them through traditional trade channels, at the end of the day he has no interest in the administrative vagaries most other publishers must conform to in order to sell books. In fact, other than publishing books, what this film drives home, in a way that will stir envy in anyone who has ever dealt with a traditional publisher, is that Steidl cares only about his vision for what a book can achieve.

In the case of "iDubai," what Steidl wants to achieve is the anti-monograph, which will not undermine the photographs but best represent them for what they are: small, off-the-cuff images captured with a phone camera. From their initial conversation about the book in Sternfeld’s New York apartment to the multiple trips Sternfeld makes to the Steidl compound in Göttingen, Germany, we see a book find its form. Trim size and paper, page layout, sequencing of the images, adjusting color to get it just right, realizing the more garish the cover and gold stamping the better – Steidl demands that he is involved with every step of production for every title that bears his imprint. This explains quite a bit, and is the reason his books rank among the finest being printed today.

Always wearing a white jacket when working, Steidl refers to his press as a laboratory, though at times he’s more like a dry physician, asking rote but necessary questions: Has the title changed? Is there a subtitle? How many pages? There is a great seriousness to everything Steidl does when it comes to his work, the seriousness of an addict. He identifies himself as such, addicted to the smell of ink and varnish, the touch of luxurious paper stocks, the sound of those sheets being pulled off the press. And like any respectable addict, if a fix is available but somehow missed, anger surfaces. At one point in the movie, Sternfeld is discussing color levels with one of Steidl’s employees. It is a civil, typical conversation to be had when looking at wet proofs. From off camera we hear Steidl bark something about having agreed to wait on this conversation until he was done doing whatever it is he’s doing out of the frame. The employee tones back that they’re just talking, better than standing there doing nothing. Steidl’s reply is fiercer, so the two men end up standing there, not talking, awkwardly waiting for the boss. With a guilty whisper Sternfeld breaks the silence accepting blame for this unexpected situation, saying to the employee that he will tell Steidl as much.

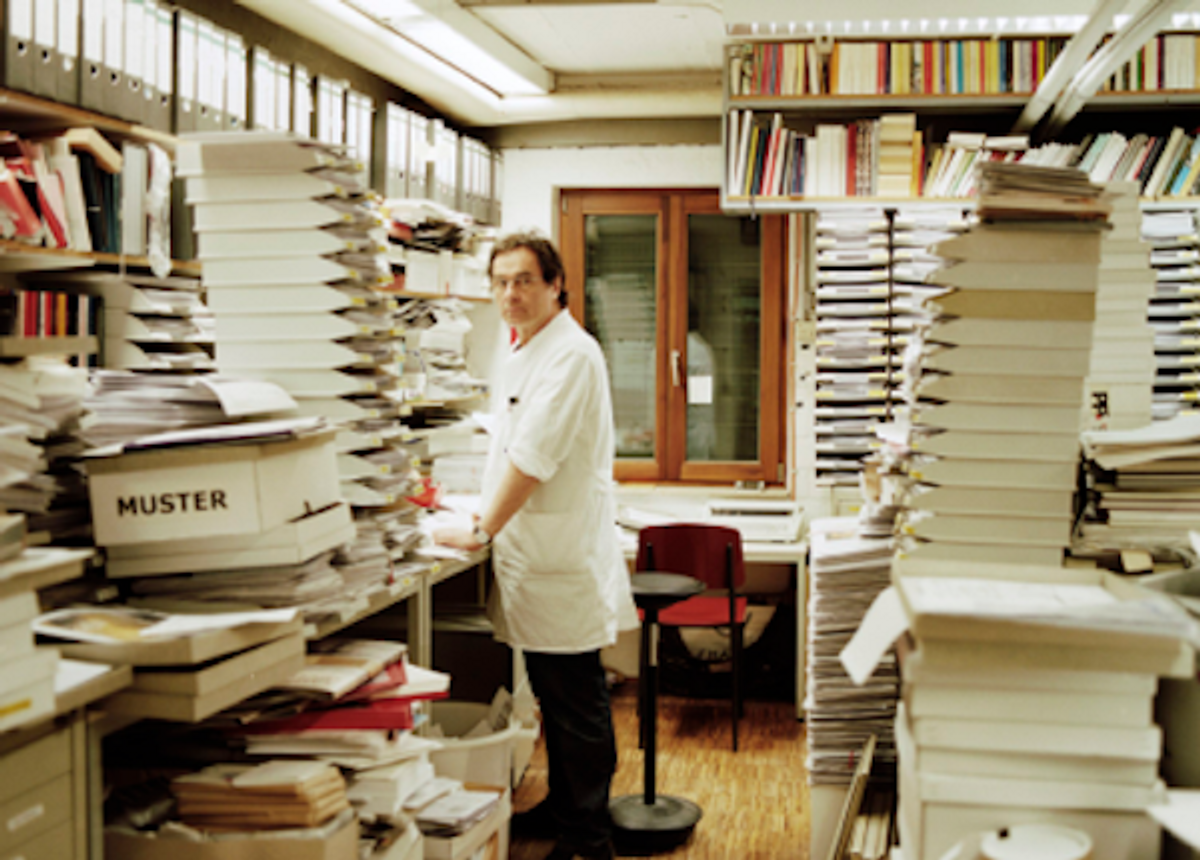

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="460" caption="Files for some of Steidl's authors, via Wallpaper*"] [/caption]

[/caption]

The guiding principle of Steidl’s output is that he views the books not as crass products but as multiples, genuine works of art. This goes for trade editions that sell for $45 as well as pricey special editions, like the oversize $11,000 letterpress edition of Ed Ruscha’s On the Road, which includes 55 tipped-in blind embossed photo plates. All of the details of each book receive an equal amount of attention from Steidl; he does not delegate and he does not take shortcuts.

In the film, the issue of money is only really touched on in terms of spending it. When Steidl meets with Ruscha about the special edition, they are trying to decide whether or not to use letterpress or offset printing. The publisher casually says it is a difference of $120,000 but that the right choice is whatever is best for the book. Giving an interview to a German media outlet, Steidl claims that his bestsellers, like The Americans and the Gunter Grass titles, subsidize all of the books that don’t make him money. But there is more to it than that, which the film hints at but basically leaves out of the story. When he is in Qatar, he hangs out with photographer Khalid Al-Thani, but he also puts on a dog-and-pony show for Al-Thani’s father, showing off a dummy for a large slipcase, waxing poetic about how it will house volumes of photography that will demonstrate Qatar’s beauty. In this scene, Steidl is basically pitching the father. In the case of Karl Lagerfeld, the film does not reveal the extent of the relationship between the fashion maven and the publisher, though it is mentioned on the film’s website; Steidl produces all of Lagerfeld’s and Chanel’s printed collateral, from catalogs to admission tickets.

Creating alternative streams of revenue makes perfect sense and Steidl deserves credit for working them in order to help pay for his books. Such tactics might take a bit of the shine off the romantic portrait of this uber publisher, but that is secondary. The point of the film is that no matter where it comes from, money is not the issue when it comes to Steidl books. As the photographer Martin Parr says at the start of "How to Make a Book With Steidl," this publishing empire is a club, and like all clubs there are rules and bylaws that members must submit to should they want to remain members. Both the artists that collaborate with Steidl and the readers that lavish in the pleasures of the resultant books should consider themselves lucky that such a club exists.

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares