Once "Riddley Walker" gets into your head, it never entirely comes out. You'll stumble across bits and pieces of it as you roam through the culture, whether it's the obvious tribute enshrined at the center of David Mitchell's novel "Cloud Atlas," or that echo in "Reign of Fire," a goofy post-apocalyptic film from 2002, in which survivors stage a ragged play you gradually recognize as a garbled, eroded version of "Star Wars."

In the post-apocalypse of "Riddley Walker," Russell Hoban's 1980 novel, the primitive theater is a Punch & Judy show (a combination of entertainment, propaganda and oracle), but the surviving bits and scraps of the world before the nuclear holocaust are similarly transformed, as if by a centuries-spanning game of Telephone. The novel, written in a broken but addictive dialect of English, recounts the adventures of its 12-year-old title character in an "Inland" bombed back to the Iron Age, where rumors of the past, before the "1 Big 1," survive in tales of Mr. Clevver and his successful campaign to persuade the hero Eusa to tear apart the "Littl Shining Man" named Addam. The definitive sign that humanity has screwed up beyond redemption? Even the dogs have turned against us.

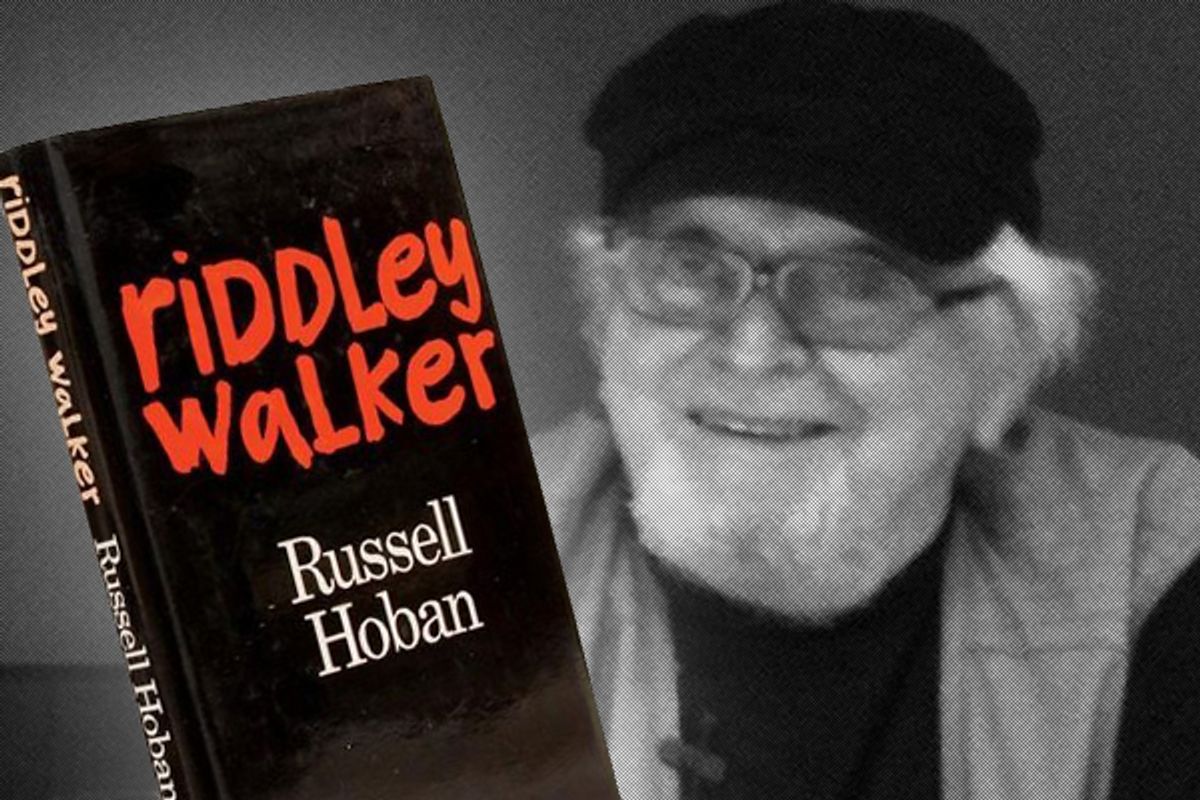

The publication of "Riddley Walker," greeted by an ecstatic front-page rave in the New York Times Book Review, was a career high point for Hoban, who died at the age of 86 last week. Some will know him best for the Frances series of kids' books (beginning with "Bedtime for Frances") created with his first wife, the illustrator Lillian Hoban. He also wrote a marvelous middle-grade chapter book, "The Mouse and His Child," about a pair of threadbare, wandering clockwork rodents, described by one critic as "Beckett for children." But "Riddley Walker" was the apex of his renown in the world of adult literature, even though he kept writing, by all reports, until the day he died.

While Hoban found it difficult, as the years when by, to publish his work in his homeland (born in Pennsylvania, he lived in London from 1969 on), as "Riddley Walker" went out of print, and then only managed to be brought back by a small university press (really, Penguin Modern Classics?), he was not without a certain fame. He was the kind of writer who inspired fans to celebrate his birthday by distributing sheets of yellow, A4-size writing paper (a recurring motif in his fiction) inscribed with favorite quotes in subway trains, parks and other public places around the world. There are websites and conventions devoted to Hoban; books, T-shirts and coffee mugs imprinted with his mottos and neologisms; and the constitutionally irreverent writer Will Self was happy to kowtow to him in an onstage interview earlier this year.

In other words, Hoban was a cult writer, perhaps the last of that pre-Internet breed. I knew that one of my closest friends would become just that when, the first time I visited his house, I found a foot of Hoban titles on one of his shelves. No one else I knew had ever heard of him. It wasn't just "Riddley Walker" that enthralled and transformed a certain small but very enthusiastic cadre of readers, either. Another friend swears by "The Medusa Frequency" (1987) in which the narrator -- pining, like so many of Hoban's characters, for an absent woman -- keeps coming across the severed head of the Orpheus on the streets of modern London and communicates with the mythic Kraken via the glowing green lettering in his Apple II computer.

For myself, I'm partial to one of Hoban's two naturalistic novels, "Turtle Diary" (1975), about two middle-aged people, living quintessentially British lives of quiet desperation, who become obsessed with freeing a pair of sea turtles from an aquarium. (This book was made into a film with Glenda Jackson and Ben Kingsley.) Like everything he wrote, "Turtle Diary" is suffused with a sweet melancholy that never curdles into sentimentality. Hoban is never going to lie to you -- "Yer tern now my tern later," says young Riddley to the wild boar he spears on page one -- which means that when he offers you freedom or respite, it rings true.

It also rings so beautifully. Was there ever a novelist with such a knack for the music of English, not just its rhythms but its keys, and who also knew not to belabor that gift? Hoban is eminently quotable, but one of my favorites of his lines, from "The Medusa Frequency," is pure description: "It was novembering hard outside; the dark air sang with the dwindle of the year, the sharpening of it to goneness that was drawing near." His ear for the jaunty gallantry of the spoken word is what makes "Riddley Walker" a delight to read, especially if you remember to read it out loud.

Not long ago, Hoban cheekily speculated that only his death seemed likely to induce a revival of his reputation. Perhaps it will. And even if it doesn't, that spark will never entirely fade away; there will always be Hobanists eager to spread the enthusiasm like the virus I strongly suspect it to be. To quote another line, this one from "The Lion of Boaz-Jachin and Jachin-Boaz," "I tell you what I have paid years to learn: everything that is found is always lost again, and nothing that is found is ever lost again. Can you understand that?" Oh yes, we can. Some of us, at least.

Shares