When Secretary of State Hilary Clinton made a historic speech in Geneva on Dec. 8 calling for recognition of gay rights and support for those who brave hostility to defend gay rights, she might have been speaking of the Rev. MacDonald Semberka who was in the audience listening.

On the evening of Sept. 11, 2011, Sembereka, a Malawian Episcopalian, found his house reduced to unrecognizable rubble by a petrol bomb. A month later, he borrowed money for airfare so he could attend a conference at Union Theological Seminary, a Manhattan institution with a long history of social activism. He arrived wearing a clerical collar and a smile that belied the horror of seeing his home and nearly everything his family owned destroyed. At the two-day conference in New York, he would meet and strategize with other Christian leaders in the fight against Africa’s perilous and increasingly prevalent brand of homophobia.

Sembereka is one of a small but growing group of African religious leaders who have taken great personal and professional hits for supporting LGBT rights. For their efforts, they have faced violence, professional alienation and social ostricization. Yet these straight men and women, primarily Christian clergy, continue to criticize the intensifying vitriol and violence against gay Africans.

The motivation behind the bombing of the house Sembereka shared with his wife, two children and extended family has yet to be determined, and the perpetrators may never be brought to justice. But Malawian human rights organizations say Sembereka was likely a target because of his outspoken pro-gay views and his valiant defense of human rights.

Fortunately, the only ones home that fateful night were two teenage boys who managed to run out unharmed. “I’m thankful that miraculously no one was hurt," Sembereka told me in an interview. “But what hurts me the most is to see my [7-year-old] daughter traumatized. She’s had bad nightmares since the attack.”

For the most part, African faith leaders have either fanned the flames of homophobia or stayed quiet on the issue. In some cases, they have been the key agitators of anti-gay attitudes in their countries.

In an interview last summer, Bishop Benjamin Nzimbi, the former archbishop of Kenya, told me that he could fix homosexuals by marrying off lesbians with gay men. Ugandan evangelical pastor Martin Ssempa has shown same-sex pornography to his congregation of hundreds in Kampala in order to rally up support for the Ugandan government’s anti-gay position.

Last month, after British Prime Minister David Cameron threatened to cut aid to Ghana unless it retracted its anti-gay policies, religious leaders there made sharp comments against homosexuality and warned against capitulation. Some of the criticism came from 53 LGBT African groups who wrote, “While the intention may well be to protect the rights of LGBTI people on the continent, the decision to cut aid disregards the role of the LGBTI and broader social justice movement on the continent and creates the real risk of a serious backlash.”

Last week, after Clinton announced a similar decision to tie U.S. foreign aid to a country’s record on gay rights, the backlash was evident. Yoweri Museveni, Uganda’s president, said of homosexuality, “It’s something anathema to Africans, and I can say that it is abhorrent in every country on the continent that I can think of.” The National Council of Churches in Kenya stated flatly, “We don’t believe in advancing the rights of gays.”

Where religion plays a significant role in the lives of many Africans, faith leaders yield great influence over politics and in setting the moral compass of most African societies. Last spring when Kenyan President Mwai Kibaki nominated Willy Mutunga, a pro-gay judge, many of the country’s religious leaders sprang into action to oppose his nomination. Making matters worse for them, Nancy Baraza, the president’s choice for the deputy chief justice, was also supportive of gay rights. For two months, substantive issues were sidelined for questions on the nominees’ sexuality.

The two nominees, both straight, were eventually confirmed as chief and deputy chief justice. Activists in Kenya and across Africa hailed this as an unparalleled victory in their struggle for equality. Longtime gay rights activist David Kuria said, “Things are changing and the most pertinent example is the nomination of the deputy and chief justice. This discredits that Africa is universally united in its opposition of homosexuals.”

Methodist Rev. John Makokah of Kenya, who’s been blasted for his pro-gay views, said, “We have a long way to go but Willy Mutunga and Nancy Baraza will help usher a new dawn for persecuted homosexuals.” But the hearings in the Kenyan parliament last summer also demonstrated the strong sway of religion on government decisions.

Generally, media reports on homosexuality in Africa have focused on the legislative push in Uganda to render certain acts of homosexuality a crime punishable by death and on the wave of lesbian “corrective” rapes in South Africa. But little attention has been given to the African activists, gay and straight, who challenge the mistreatment of gay Africans and the criminalization of homosexuality in 38 of 54 countries in Africa.

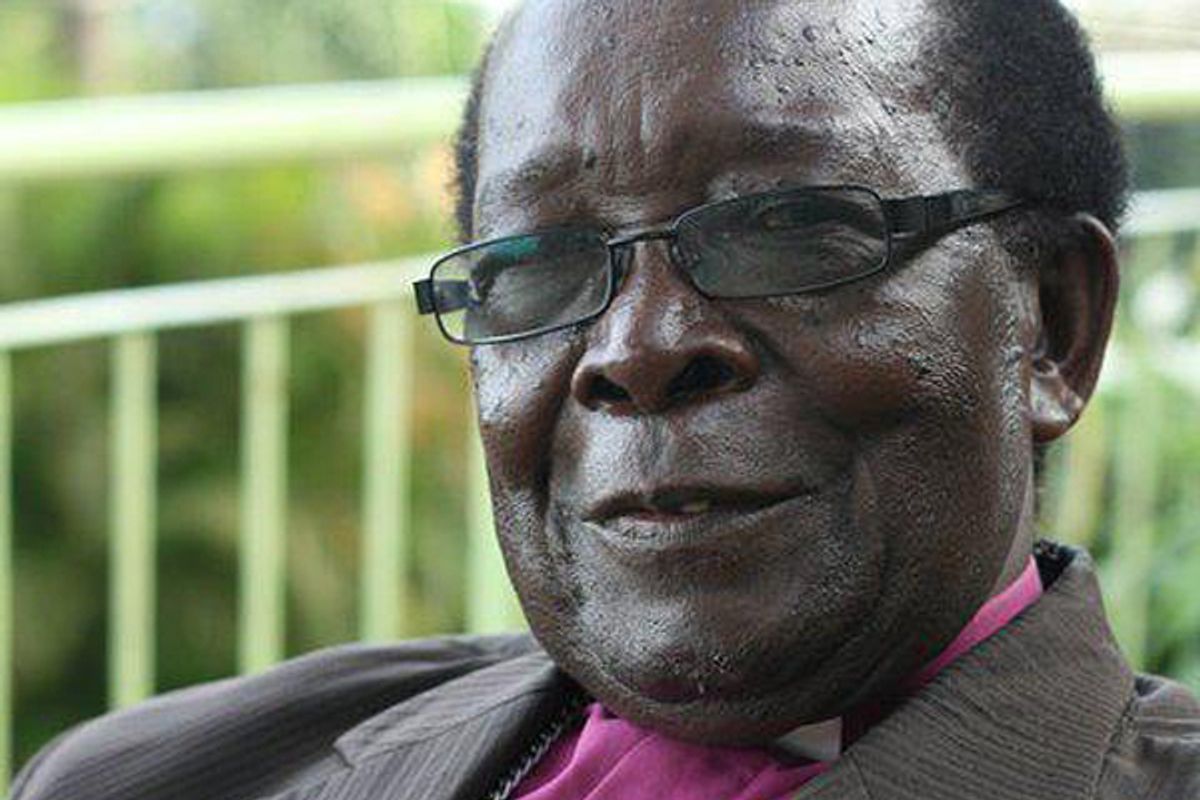

For example, Bishop Christopher Senonjo, a retired 80-year-old Anglican Bishop from Uganda, has been a beacon of support for LGBT Ugandans since 1998 when he began to counsel gay men and women. Around the same time, a group of gay men founded one of Uganda’s first gay groups and asked the bishop to chair the organization. His decision to accept the invitation would lead to years of persecution. Because of his support of homosexuals, he would be ostracized from the church, stripped of his pension and precluded from performing his religious duties.

But he says the most difficult part of his ordeal has been the backlash against his family. Recently, his daughter’s fiancé broke off the engagement because he said he didn’t want to be associated with a family who held pro-gay views. But early on, he says, even his family had their doubts. His wife, Mary, 73, did not understand or agree with what he was doing but, laughing and showing his toothy smile, he said, “God changed her heart.”

Today, Mary is a quiet force of support for her husband and the LGBT individuals she meets through his work. When a Ugandan lesbian broke down into uncontrollable tears at the conference in New York, Mary scooted her chair to where the woman was sitting and rubbed her back till she stopped sobbing and stayed by her side for the rest of the day.

Albert Ogle, president of St. Paul’s Foundation for International Reconciliation, a faith-based organization headquartered in San Diego, says that the Senonjo and Sembereka “are fueled by a moral value, which is about including all the marginalized in ministry and service. It’s not that their mission is about gay rights necessarily but to serve all humanity.”

By the end of the conference Ogle and those in attendance formed a coalition, which they dubbed “Compass to Coalition” to combat punitive laws and attitudes toward LGBT people in Africa and in the 76 countries around the world where it is illegal to be gay.

Anglican priest Michael Kimindu of Kenya says religious leaders in Africa have to be at the helm for changing attitudes toward gay people. Like many of his counterparts, he’s also been banished from the church and alienated from family members for his work with LGBT Kenyans. “We can’t let them be treated this way,” he says of gay Kenyans. “The church has to lead in bringing dignity to these people.”

When Sembereka took the stage at the conference, he also spoke of the formidable challenges that he and other LGBT-affirming faith leaders faced: “We are branded as Western puppets or gay ourselves.” He added that these attacks would not stop him or his colleagues from continuing to fight the unnecessary persecution of people of diverse sexualities. Later when asked about his destroyed home he said, “That too will be something of the past just like the plague of homophobia.”

Shares