I don’t even remember how it began.

My eldest sister is in my apartment, screaming and yelling at me with a nonsensical fury. There is something about my not going to work. There is something about my going out late at night. Is this woman crazy? I shut down her every attack with calm but assertive responses, revealing the faults in her strange accusations. The exchange is escalating wildly, but she is unable to faze me. Finally, in an angry, spiteful resignation, she says, “You’re just a faggot.”

The shit was about to hit the fan. And, seeing this, everyone who intruded into the apartment with her — her husband, my brother — tries to pull her out of my path.

Growing up, I’ve always been the black sheep of my family. I was ripped away from my refugee parents when I began kindergarten, English gaining importance over the Khmer I spoke at home. My mother once threatened to disown me if I pursued the predominantly female art form of Cambodian classical dance. And, in line with the combination of my youthful independence and my family’s inability to guide me through American society, I defied my parents and left to study experimental filmmaking at the San Francisco Art Institute.

And now here I am, crying my eyes out in angry confusion, back with the family that my path has torn me from -- back in my sleepy hometown of Long Beach -- that has been nothing but cycles of poverty, ignorance and violence.

What the hell was I doing here? And how in the world did so much hatred come from my own family?

I grab my phone. I dial the number to my father’s house, and he picks up with his voice of aged calm. It is a calm that comes from having lived for 82 years, from living at the mercy of the land, sun and water in rural Cambodia. It is a voice that has lived through French colonialism, the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge genocide, and now, displacement and alienation in America. I begin in tears, speaking in Khmer, “Pa, guess what your daughter did? Who the fuck does she think she is?!”

“What’s going on?”

“Pa, I’m gay! I don’t care if you don’t approve. I don’t need your love if you don’t respect me! I don’t need it!” I am crying uncontrollably, and there is no response on the other line.

“Prum… Prum,” my father says after what feels like an eternity of drowning in my emotions. “Calm down. You are my son. And you’ll always be.”

My heart lifted. Surprise began to mix with the chaotic flowing of emotions. I think I just came out to my 80-something father, and he was OK with it. And it wasn’t the last time.

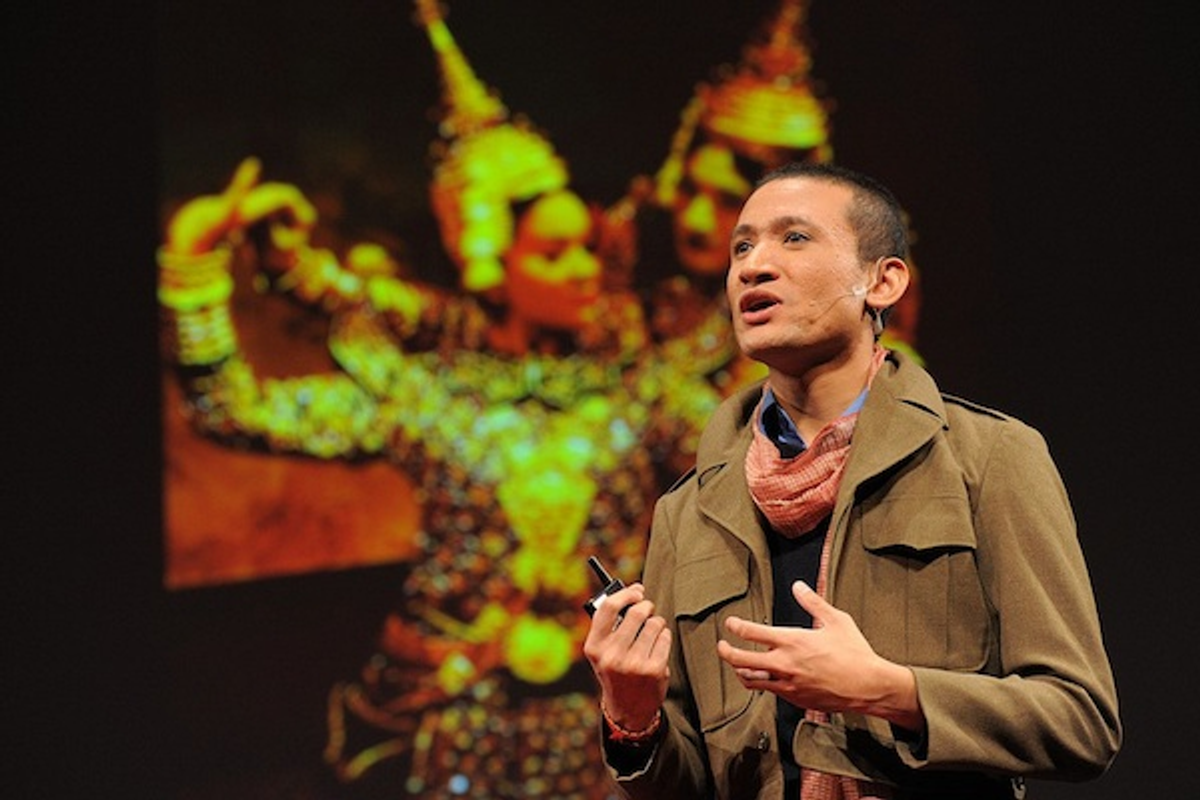

Things seemed to happen quickly after that. I was creating a visible place for myself as an artist in California through shows, fellowships and public talks.

Looking back at the incident, I'm perplexed at how it happened that way. First off, in the context of Cambodian classical dance — the epitome of Cambodian culture — there is a space for those who don’t conform to hetero-normative molds of man and woman. During the height of Cambodian dance ritual, a lone Brahmin who is half male and half female appears to act as a messenger between heaven and earth. This sacred, divine sanction of queer is echoed in contemporary Cambodia, where men can have wives and boyfriends, and female pop stars enact homosexual romances.

My sister’s attack came off as an erasure of cultural memory, perhaps at the hands of colonialism and the fear-driven puritanism of American society. As a result, my original dance works became increasingly political, and I was preparing to present one of them at REDCAT, the premier venue for experimental performance in Los Angeles.

At this time, a reporter from the LA Times was interviewing me (for a story that never ran). She wanted to speak with my father. We met at the dance studio where I was teaching. After questions about my father’s life, she asks me, “So what does your father think about your being gay?”

“Pa, she wants to know how you feel about my being gay.”

“You’re gay?”

Oh dear. “Yes, Pa, I’m gay! Don’t you remember? I was crying on the phone and I was telling you.” The reporter is obviously wondering what is going on, as both my father and I seem confused. “I’m sorry. He’s old. And he’s forgotten that I told him that I was gay,” I say to her in English.

I ask in Khmer, “Well, Pa?”

“What is there to say? You are my son. I love you no matter what. As long as you are a good person, nothing else matters.”

My father, Sem Ok, passed away two years later, on Jan. 20, 2011. It was my 24th birthday. May he be remembered for his love.

Shares