When Harris Wofford first heard about the second-term congressman from the Pittsburgh suburbs who was interested in challenging him for his U.S. Senate seat, he did some scouting and watched his would-be opponent deliver a speech on the House floor. The verdict? "I came back and said, 'He's young, makes a strong appearance, and he's articulate and bold," Wofford recalled in an interview this week.

Not that he thought Rick Santorum would actually manage to beat him in 1994. After all, Santorum, then 36, entered the race as much out of desperation as ambition, his House reelection prospects ravaged by redistricting. And Wofford was a certified political star, the underdog who'd channeled working-class economic anxiety into a stunning upset victory over Pennsylvania's most popular Republican in a special election just three years earlier.

"I underestimated him," Wofford admitted. "I also underestimated the wave that was rolling in the '94 election."

As a presidential candidate today, Santorum frequently invokes his 1994 win over Wofford as proof of his ability to win over traditionally Democratic voters in a blue-tinted state -- "the same people that President Obama talked about who cling to their guns and their Bibles," as he put it in his post-caucus speech in Iowa Tuesday night. Of course, Santorum ultimately lost his Senate seat in an 18-point landslide in 2006, but in the Obama era the same basic resentments that his cultural conservatism tapped into all those years ago are prevalent once again.

"In many ways," said Wofford, "it was remarkably like the wave that has been rolling since 2009 and the Tea Party."

Word that Santorum would run for the Senate in '94 began spreading almost as soon as the 1992 election ended. He had won his bid for a second term in the House by 21 points, but the margin was deceptive: Santorum's survival had been a miracle.

Redistricting in early '92 had transformed his district into a Democratic bastion -- fully 71 percent of its voters were registered as party members. What saved Santorum was that the ensuing 12-way Democratic primary had been won (with 19 percent of the vote) by a state senator -- Frank Pecora -- who had been elected as a Republican and who then changed his registration when GOP leaders failed to protect his legislative district in redistricting. But Pecora still embraced Republican positions and caucused with Republicans in Harrisburg, so Democratic leaders shunned him in his race against Santorum, who got a free pass -- but who also knew that Democrats wouldn't make the same mistake again two years later.

So Santorum turned his attention to the Senate seat held by Wofford, whose late-in-life political career had been something of an accident. At 65, he'd been tapped in May 1991 by Pennsylvania Gov. Robert Casey, his longtime friend, to fill the seat vacated by Republican Sen. John Heinz's sudden death in a helicopter crash. Wofford had helped launch the Peace Corps under John F. Kennedy and gone on to serve as the president of two colleges (SUNY-Westbury and Bryn Mawr) before agreeing to join Casey's Cabinet as secretary of labor and industry.

His Senate appointment was supposed to be temporary: Richard Thornburgh, the moderate Republican who was serving as George H.W. Bush's attorney general and who had been governor from 1979 to 1987, decided to run in the special election and led early polls by more than 40 points. But the economy was slowing and popular anxiety was rising, especially in the Northeast. Wofford declared himself the "chief prosecutor" of Bush's domestic record and adopted national healthcare as his signature issue. "The Constitution says that if you are charged with a crime, you have a right to a lawyer," he would tell voters. "But it’s even more fundamental that if you’re sick, you should have the right to a doctor."

Wofford's shocking 10-point victory provided the blueprint for Bill Clinton's own campaign against Bush the next year -- a campaign that was led by the same guy who'd been Wofford's chief strategist, James Carville. "I would joke sometimes that I was the guy who helped Carville win that big race," Wofford said.

But once Clinton entered the White House in 1993, the political climate shifted dramatically. Conservative leaders and activists mobilized to fight the new president and his agenda, warning of creeping socialism and radical assaults on traditional values and fomenting a fierce backlash that was particularly pronounced among white working-class voters. Clinton's approval numbers plummeted and Democrats found themselves on the run as the '94 midterm elections took shape.

In Pennsylvania, two specific issues animated the backlash: guns and abortion. Under Clinton, a five-day waiting period for the purchase of a handgun and an assault weapons ban had been enacted, while his push for healthcare reform had opened up a polarizing debate over whether abortion should be covered, with conservatives and religious leaders calling for a strict ban. Santorum derided Wofford as Clinton's "lapdog" and emphasized his own Second Amendment absolutism and Catholic-infused opposition to abortion.

Wofford remembers when he realized just what he was up against. His campaign had organized a caravan tour of the state, but when he arrived for a speech to local Democrats on a town green in rural north central Pennsylvania, he was told that plans had changed: A local militia group had taken over the green in protest and the Democrats had fled to a nearby hotel basement. Wofford was asked to talk to the party faithful there.

"And I told them, 'I'm not going to do that,'" he recalled. "So I went to the green and had a 20- or 30-minute talk surrounded by 40 or 50 of the militia people, who began by saying, 'Senator, we should tell you that last night the militia of this county convicted you of treason.' I said, 'Well, that's pretty serious -- the punishment for treason is death.' And he said, 'Well, we just want to defeat you.' He didn't admit to wanting to kill me."

Wofford laughs about the incident now and says he had "a moderately good time" and held his own -- and that he even managed to win over one of the militiamen on the need for universal healthcare. But the anger he encountered was a powerful sign of the general mood of '94. So were the target sheets, which his campaign learned were available at gun clubs in the state. "It was a target and it said, 'Get the real enemy.' And in the bulls-eye was my name, Harris Wofford. And it said that a dollar from each sheet would go to the Santorum campaign."

Santorum disavowed the targets, and Wofford says he believes he didn't know about them, "but you ask me when I really had a sense that things were serious -- that was probably it."

Abortion was even more problematic for Wofford, whose calling card was healthcare reform. As Congress was considering various reform proposals in 1993 and 1994, conservatives rallied around an amendment authored by Indiana Republican Sen. Dan Coats that would ban abortion from being covered by any plan that had anything to do with any national health insurance program. It was, in effect, a poison pill, with some pro-choice Democrats declaring that they couldn't support any reform law that included the Coats language. As the debate raged, Wofford received a surprise visit from Casey, who was then the most prominent pro-life Democrat in America. (He'd famously been denied a speaking slot at the 1992 Democratic convention because of his desire to address the subject.)

"He came down and made a special trip and said, 'Unless you will support the Coats amendment, I'm not going to be able to support you,'" said Wofford. "I think he assumed that would make me support it."

But Wofford refused, and the consequences for his reelection bid were severe. Casey, whose friendship with Wofford went back decades and who had once described Wofford as "my hero," refused to lift a finger from that point on, further isolating the senator from the state's blue-collar Catholic voters.

Nor did it help that voter guides prepared by the Philadelphia archdiocese and distributed to hundreds of thousands of Catholics just before the election went out of their way to portray Wofford -- who was actually far closer than Santorum to the church's positions on economic and social justice issues -- as their enemy.

In the closing weeks, polls showed Wofford falling behind by double-digits. But he caught two late breaks. One was courtesy of an unguarded Santorum moment. Speaking to students at Temple University, he'd claimed that the only way to preserve Social Security would be to raise the retirement age to "at least" 70, giving rise to a devastating Wofford ad. And then Heinz's widow, Teresa, decided to speak out, calling Santorum an unaccomplished extremist -- "critical of everything, impossible to please, indifferent to nuance, incapable of compromise." Teresa Heinz is now known as an outspoken liberal and the wife of Sen. John Kerry, but back then she was still closely identified with the moderate wing of Pennsylvania's Republican Party.

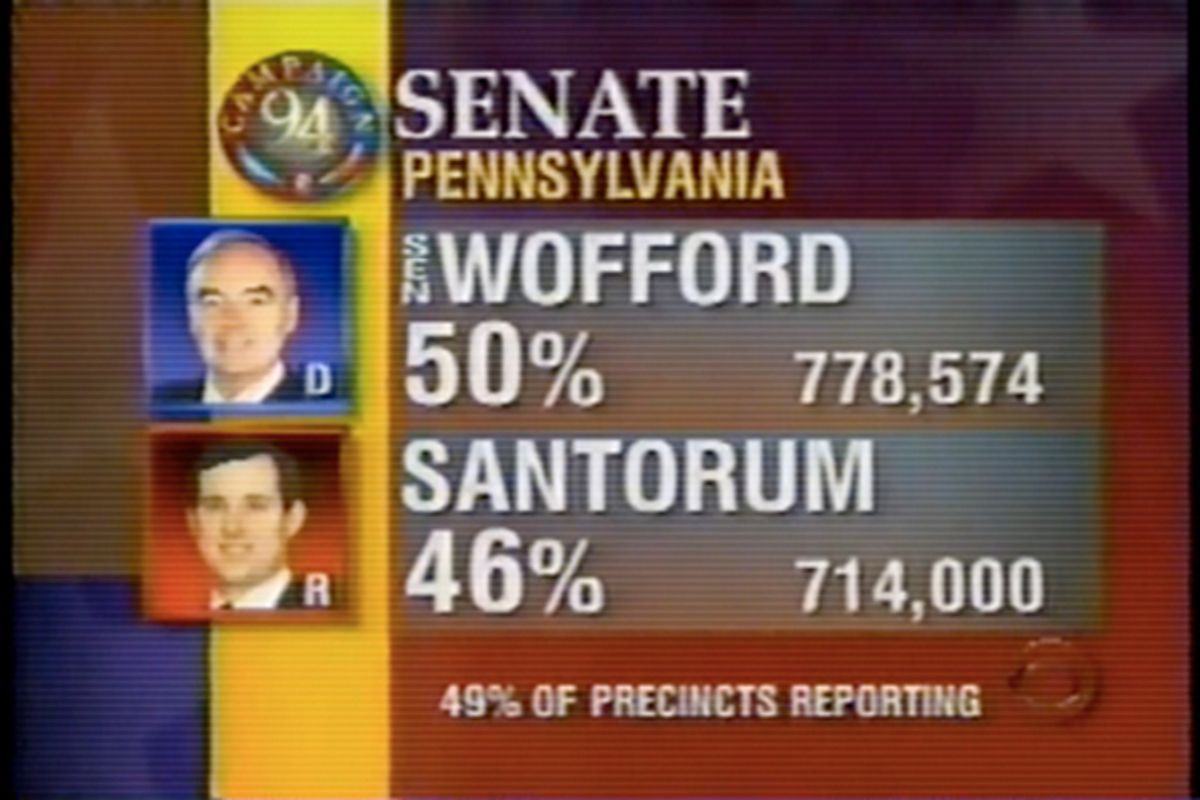

By the campaign's final week, Wofford pulled ahead by several points. And on election night, early returns put him ahead (as the image accompanying this story shows). "Everyone around us was celebrating," he said, "because we seemed to be nicely ahead by 9 o'clock, 10 o'clock. But our pollster looked at precincts from the areas that had not yet reported and said, 'You'd better get ready for a concession speech.'" The final margin was 2 points, 49 to 47 percent.

"We could have survived the wave that was striking the Democratic Party that year," Wofford said, "but for the prominence of guns and abortion."

Shares