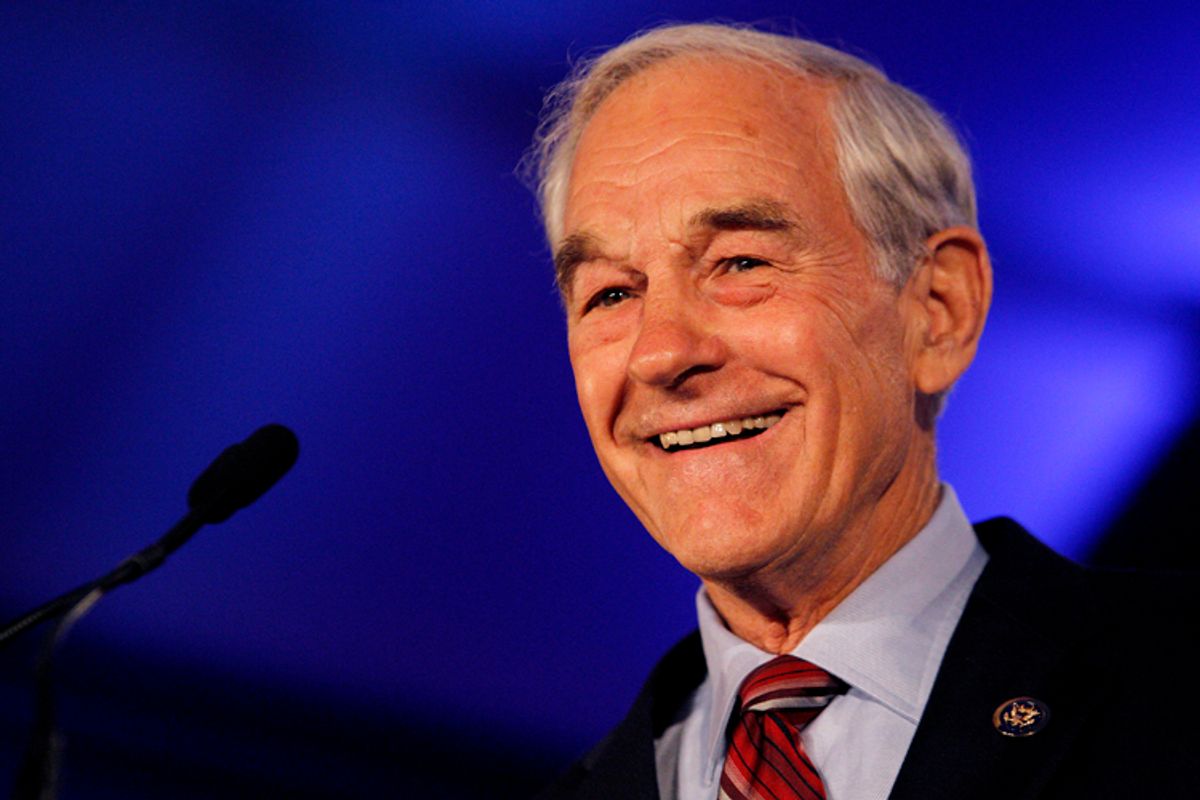

Anyone who has ever woken up bleary-eyed, woozy after a night of drunken revelry, knows about the phenomenon of “beer goggles,” and how embarrassing it can be. You wonder, staring at the shapeless form under the sheets next to you: What did I ever see in this gal/guy? I’m beginning to think that there is such a thing as political beer goggles. I’m referring to the surprisingly positive view that some progressives hold of the most reactionary figure in modern American politics, Ron Paul.

A number of commentators I respect greatly are finding aspects of Paul’s platform to be compelling. Among them are Glenn Greenwald on this site and Matt Stoller at Naked Capitalism. Greenwald points out that “Ron Paul is the only major candidate from either party advocating crucial views on vital issues that need to be heard, and so his candidacy generates important benefits” [his emphasis]. He goes on to provide a long list of Obama’s shortcomings that, he points out, are not shared by Ron Paul. Stoller argues that “the anger [Paul] inspires comes not from his positions, but from the tensions that modern American liberals bear within their own worldview.”

I couldn’t disagree more. What I find objectionable about Ron Paul is very much related to his positions, which I view as an organic whole, divergent from progressive values on every single vital issue, including the foreign policy views that are the main attraction he holds for some liberals. Unlike Greenwald and Stoller, I don’t find any solace in his positions on foreign policy, or his desire to disentangle the U.S. from Afghanistan. I can’t quite so comfortably carve out Paul’s views on defense and foreign policy. To me, that’s like trying to scrape peanut butter off the business end of a mousetrap.

In a sense, Paul is emerging as a protest vote for two separate and usually irreconcilable constituencies: traditional conservatives who want to slash the size of government to the bone, and young people and progressives who are opposed to the war. I don’t have much to say to the former. Paul is their man. But voters who want to protest the endless war in Afghanistan should realize that a protest vote for Paul is also a protest vote against the very role of government in society. Do they really want to cast such a vote? Is a protest vote quite so important? Are their better ways of opposing the war? Greenwald, to his credit, does not advocate voting for Paul, but that is one logical implication of his position.

Those considering a protest vote for Paul need to weigh its cost and implications. The more one digs into the weeds of Paul's record, the more one is overwhelmed by the stench.

My feelings on that point were reinforced when I used a database to reach back to 1997, when Paul returned to Congress after a lengthy hiatus, and examined every floor speech that Paul made in his first term back on the Hill.

I didn’t catch him in any racist riffs. What I found, instead, was much worse than casual bigotry. It was the mindset of a doctrinaire follower of Austrian economics and Ayn Rand—a fervent advocate of laissez-faire economics, the primacy of “market forces,” and a philosophy of government that allows for only the most limited government. While his views are never expressed in brutal, screw-the-poor terms, you have to ask yourself: Are such positions ever expressed in brutal, screw-the-poor terms? You also have to wonder, as you read the following, whether his record on foreign policy is worth endorsing this kind of baggage.

This is a politician who is, as advertised, consistent, but consistent in a kind of moral myopia. I’m not cherry-picking. I'm talking about amoral views comprising his entire program, and by that I would include foreign affairs, in which he opposes not only the war in Iraq and intervention in Afghanistan, but any kind of foreign involvement by the U.S., including humanitarian intervention against overseas genocide.

What I also found was the phenomenon that Thomas Frank identified in his 2004 book, "What’s the Matter With Kansas?": positions that would intentionally screw the people supporting him, and his supporters either not knowing or not caring.

I wonder how many of Paul’s progressive supporters are aware that Paul is so virulently anti-abortion that on March 19, 1997 he said on the House floor that “ I am convinced that abortion is the most important issue of the 20th century”?

I wonder how many of his young liberal fans are aware of his views on scholarships and low-interest loans for college students—that there shouldn’t be any? In a speech inserted in the Congressional Record of April 22, 1998 entitled “Education in America is Facing a Crisis,” Paul talked up his rather innocuous (and sensible) idea to exempt from taxation income earned by farm kids at 4-H and Future Farmers of America fairs. “We say the only way a youngster could ever go to college is if we give them a grant, if we give them a scholarship, if we give them a student loan. And what is the record on payment on student loans? Not very good. A lot of them walk away.”

OK, that’s a fair statement. But then Paul displayed his rigid ideological agenda: “

There is also the principle of it. Why should the Federal Government be involved in this educational process? And besides, the other question is, if we give scholarships and low-interest loans to people who go to college, what we are doing is making the people who do not get to go to college pay for that education, which to me does not seem fair. It seems like that the advantage goes to the individual who gets to go to college, and the people who do not get to go to college should not have to subsidize them.” [My emphasis]

That’s straight out of Ayn Rand—the view that aid to one segment of society “loots” other segments of society. Thus government-sponsored low-interest loans and scholarships are a form of theft.

Paul again channeled Rand on July 20, 1998. Explaining his opposition to a child nutrition and WIC plan reauthorization bill, he attacked the “flawed redistributionist, welfare state model that lies behind this bill.” Then he launched into another monologue:

“Providing for the care of the poor is a moral responsibility of every citizen,” he said. “However, it is not a proper function of the Federal Government to plunder”—that’s straight out of Rand—“one group of citizens and redistribute those funds to another group of citizens. Nowhere in the United States Constitution is the Federal Government authorized to provide welfare services. If any government must provide welfare services, it should be State and local governments. However, the most humane and efficient way to provide charitable services are through private efforts. “

Humane and efficient for whom, I wonder? Certainly not the poor, who would be transported back in time to the 19th Century. Note the ideological consistency. He’s often praised for that, and I’ve never understood why. What we see here is a rigid worldview, a person unwilling to adapt to reality, no matter how much his ideology might hurt people less fortunate than himself.

It goes on and on like that—the opposition to social programs to benefit the poor on “constitutional” grounds; the monotonous references to “fiat money” as causing the Asian financial crisis of 1998. Paul was rightly critical of that year’s Fed-sponsored bailout of Long-Term Financial Management, the hedge fund whose reckless bets almost brought down the entire financial system, in a precursor to the 2008-2009 financial crisis. But Paul is not concerned in the least about the regulatory neglect that allowed LTCM (and later would allow the major banks) to spin out of control. His sole focus is the Federal Reserve, which he would like to end, and the gold standard, which he would like to reinstate.

Although his backers—including some progressives—contend that Paul is an opponent of the “big banks” and former Fed chairman Alan Greenspan, in fact no member of Congress, and no Wall Street executive, was and is more virulent in his opposition to financial regulation than Ron Paul. Yes, Paul was critical of Greenspan—because of his approach to monetary policy. On deregulation, they were soul mates.

In a floor speech on April 16, 1997, opposing pro-consumer legislation concerning private mortgage insurance, Paul said: “Just this past weekend, Alan Greenspan explained why consumers are often better served by private market regulations rather than government intervention. He said that, quote: Government regulation can undermine the effectiveness of private market regulation and can itself be ineffective in protecting the public interest."

"With this, I concur," Paul said. By the way, what Paul calls "private market regulation" is shorthand for “no regulation.”

Paul’s views are rooted in the narrow, Randian view of liberty as extending only to the person, not to groups of people. That sounds elegant until you realize what it means: no consumer legislation, no civil rights legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and, as was a hot topic in 1998, no hate-crime legislation.

His foreign policy views don’t salvage him. Some on the left conflate his 1930s-style, right-wing isolationism with their opposition to the “American empire.” Pretty much everything that Paul has to say about America’s role in the world could have, and did, come from Charles Lindbergh at America First rallies. Or Robert Taft, the New Deal foe and leading isolationist of the pre-war era, whom Paul cited by name in a speech to his supporters Tuesday night. Paul’s isolationism is the isolationism of Ayn Rand, who, like Lindbergh and Taft—and Paul—opposed U.S. participation in World War II. Like Paul, she was opposed to the United Nations—and yes, also opposed the Vietnam War, the military draft, and the war on drugs.

Those positions—also consistent, also heartfelt, also at variance with the Republican Party of her time—made Rand popular among many young people in the 1960s and 1970s. But her other views, which included opposition to the Civil Right Act of 1964 for the identical reasons articulated by Paul, made her toxic, isolated, marginalized—very much as was Ron Paul, until his recent surge in popularity.

Would the anti-interventionist, anti-draft, anti-anti-drug-war Rand be attractive to progressives if she were alive today? I think she might, and that’s why I think it’s important to be aware of the principles your political bedfellow truly stands for. You might not feel so great when the beer goggles wear off.

Shares