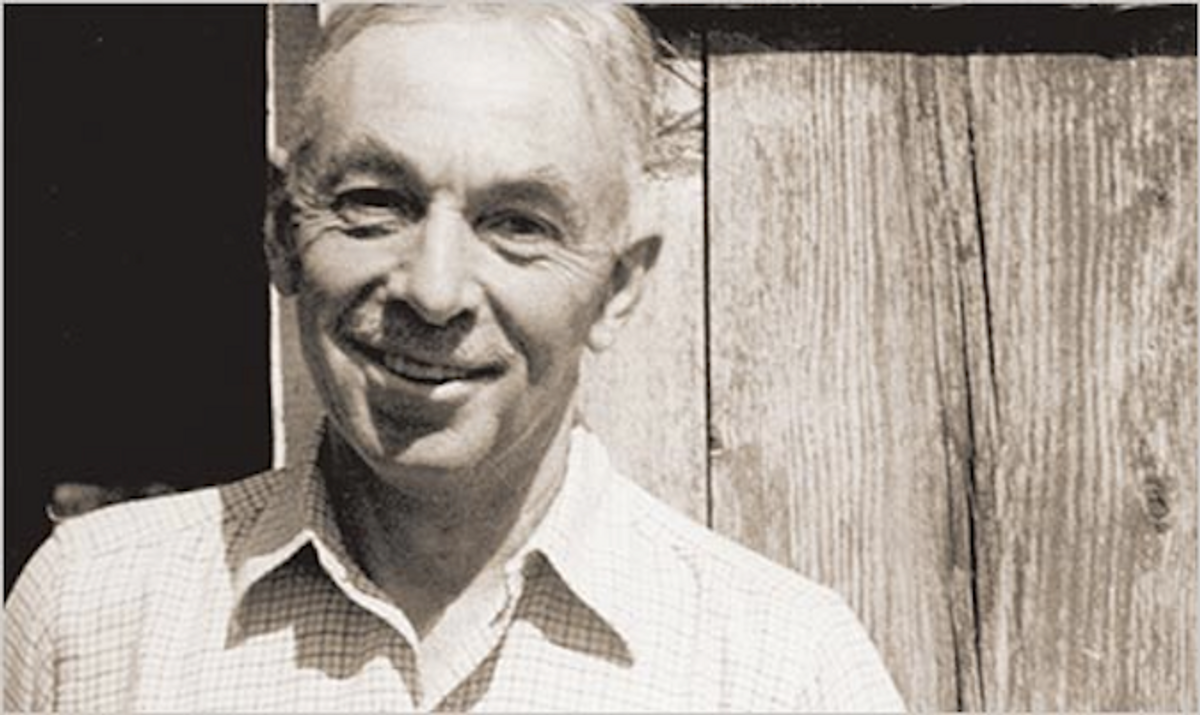

E.B. White is one of those writers you are liable to meet again and again in the course of a reading life, each time wearing a different expression. To children, he is the author of the classic animal tales "Charlotte's Web" and "Stuart Little"; to college students, he is half of Strunk and White, the authoritative guides behind "The Elements of Style." Later on, he may turn up as the urbane humorist who helped define the voice of the early New Yorker, or the Maine farmer who learned about enduring values from tending his chickens and pigs, or the earnest liberal who upheld free speech during the McCarthy period.

Now all those Whites have been brought together in the pages of "In the Words of E. B. White: Quotations From America's Most Companionable of Writers," an anthology of quotations edited by his granddaughter Martha White. Appropriately, the book is published by Cornell University Press: Cornell was White's alma mater, the place where he got his first newspaper experience and picked up his lifelong nickname, Andy (after the university's founder, Andrew Dickson White). In her introduction, Martha White offers an affectionate sketch of her grandfather's career, including her own memories of the "lifelong sense of wonder" he brought to all his endeavors.

Now all those Whites have been brought together in the pages of "In the Words of E. B. White: Quotations From America's Most Companionable of Writers," an anthology of quotations edited by his granddaughter Martha White. Appropriately, the book is published by Cornell University Press: Cornell was White's alma mater, the place where he got his first newspaper experience and picked up his lifelong nickname, Andy (after the university's founder, Andrew Dickson White). In her introduction, Martha White offers an affectionate sketch of her grandfather's career, including her own memories of the "lifelong sense of wonder" he brought to all his endeavors.

It's not hard to see why she chose the word "companionable" to describe White's writing. In person, he was famously shy -- James Thurber, his fellow New Yorker writer, described the way White would slip out of his office by the fire escape rather than receive visitors. But on the page, White was indeed an easy companion, never intimidating the reader with erudition or experiment. He exemplified the virtues he tried to teach in "The Elements of Style":

Young writers often suppose that style is a garnish for the meat of prose, a sauce by which a dull dish. Style has no such separate entity.... The beginner should approach style warily, realizing that it is himself he is approaching, no other; and he should begin by turning resolutely away from all devices that are popularly believed to indicate style -- all mannerisms, tricks, adornments. The approach to style is by way of plainness, simplicity, orderliness, sincerity.

But unlike Ernest Hemingway, whom White famously parodied in "Across the Street and Into the Grill," there is nothing austere about White's plainness. It is, rather, a vehicle for straight-faced, self-deprecating humor. "Writers ... who take their literary selves with great seriousness are at considerable pains never to associate their name with anything funny or flippant or nonsensical or 'light,'" he writes. "They suspect it would hurt their reputation, and they are right." White himself had no such fears, and he often appears in his own work as a comic figure, especially when he writes about his unlikely career as a farmer. "In the minds of my friends and neighbors who really know what they are about and whose clothes really fit them, much of my activity has the quality of a little girl playing house. My routine is that of a husbandman, but my demeanor is that of a high-school boy in a soft-drink parlor."

But this smiling demeanor shouldn't be mistaken for flippancy. Just underneath the surface, White writes as an earnest upholder of American values, a writer in the libertarian tradition of Thoreau. "Walden" was his favorite book -- "the only book I own, although there are some others unclaimed on my shelves" -- and he sees his own farm as a similar experiment in independence and authenticity. Like Thoreau, too, White stood up for the rights of the individual against the pressure to conform: "one of the noblest attributes of democracy is that it contains no one who can truthfully say, of two pots, which is the cracked, which is the whole." In all these ways, "In the Words of E. B. White" offers a perfect introduction, or reintroduction, to a writer truly in the American grain.

Shares