It is a truth pretty generally demonstrable: A shrewd eye for the complexities of human nature does not guarantee its bearer an enviable love life. Still, it does often go hand in hand with the descriptive powers necessary to craft a lasting literary classic.

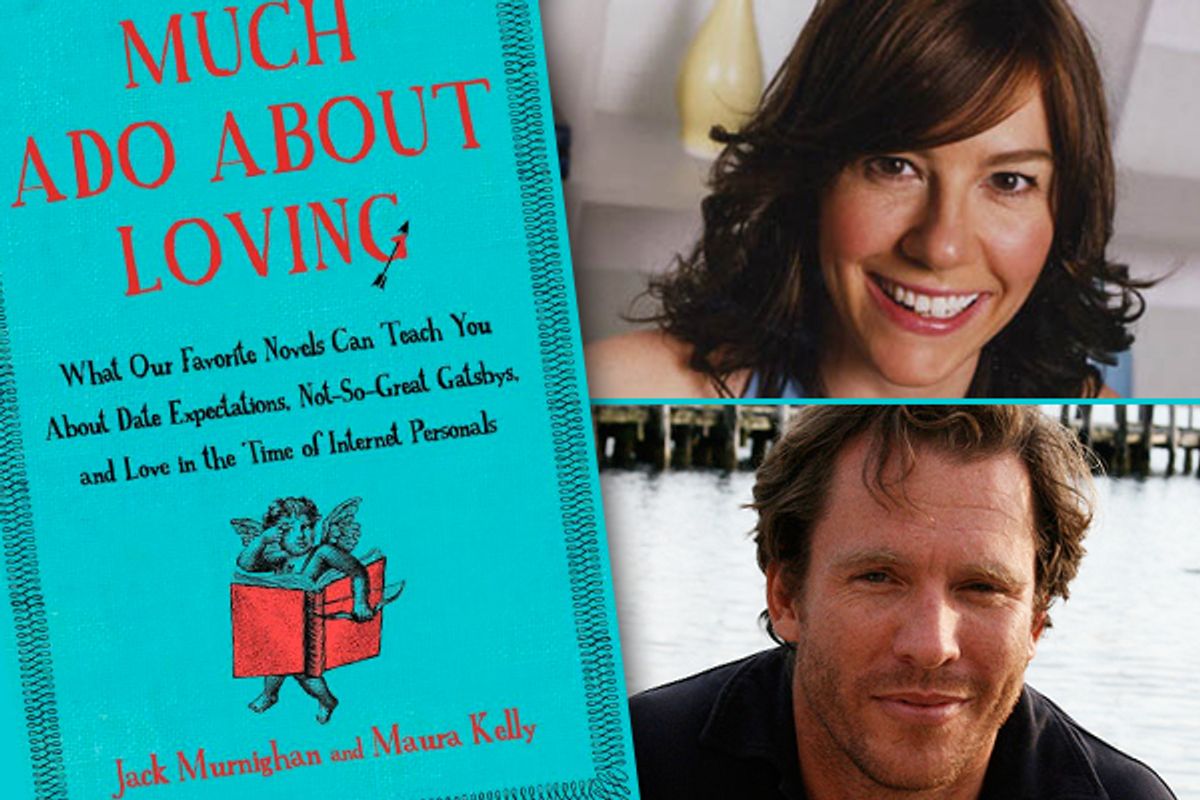

That's one of the ideas addressed by journalist Maura Kelly and writer (and medieval literature scholar) Jack Murnighan in their new book, "Much Ado About Loving," which draws advice on matters of courtship, sex and marriage from authors as diverse as Virgil and Sylvia Plath.

Over email, the pair told Salon about their inspiration for the project -- and some of its most surprising revelations.

How did you two start working together, and how did the idea for this book emerge?

Maura Kelly: Jack and I got to know each other after I wrote a profile of him for the Daily Beast, pegged to the release of his previous book. We became friends, in part because we liked talking about the books we were loving, and the people we were loving -- or trying to love. I was always asking Jack for advice about my dating conundrums. And a lot of times, when we'd be hanging out at his place, he'd start telling me how I should take a lesson from a novel. When I was dating a sourpuss academic, he reminded me of the cautionary tale of "Middlemarch," for example. (In that book, the main character gets married to an arrogant guy who's devoted his life to writing a scholarly work -- and boy, is she miserable.) Eventually, I began to think, I should bottle Jack and begin selling him to all my friends. Then I thought, Hey, we should write a book!

Jack Murnighan: Ha ha. Yes, after many attempts to fit inside a bottle, I concluded that writing a book would be much easier.

In the introduction, Maura notes that while several of the great writers you discuss -- specifically Austen, Dickens and Tolstoy -- were sharp social observers, they had messy (or, in Austen's case, uneventful) love lives themselves. How (if at all) should this color our interpretation of their characters' romances?

MK: It's a do as I say, not as I do kind of thing. Those authors weren't saying, "Live as I live." They were saying, "We are great amateur psychologists and great observers of life, and we have observed great lives -- and failed, unhappy lives -- and here's what they look like." Turns out, they didn't look all that much like the lives of the authors!

JM: I can speak from experience that one learns a lot more from failure than from success. Maura and I are both pretty sanguine that our various checkered dating pasts helped give us a lot of the perspective that we share in the book.

What do you think readers might consider the most surprising example in the book?

JM: I was quite taken with Maura’s conclusion in the first chapter (based on Sylvia Plath’s "The Bell Jar") that if you don’t find any guy good enough, it might actually be your problem. I also tend to get pretty surprised looks when I say that one can find the formula for how to be attractive to everyone in "War and Peace." Not exactly most people’s idea of the go-to book for dating advice!

Of all the authors whose work you cover, whose romantic observations do you think are the most consistently true to life?

MK: My money might be on Tolstoy -- in all those pages, he had the time (and, of course, the writerly skill) to create relationships that so much resemble the ones we encounter in the real world. But I feel a real emotional kinship with Dostoevsky and Dickens, I guess.

JM: I would agree with Maura’s list and also add both Gabriel García Márquez and D.H. Lawrence. I think they had extremely deep understandings of both psychology and human passion.

Do you think 21st-century readers who devour the classics run the risk of measuring themselves against unrealistic romantic examples -- since in so many cases, ideals and realities were very different for men and women in past centuries? (E.g., will a female Austen-worshiper venture into the world of romance with unrealistic expectations of what she is likely to find?) Or do you think most of these books offer more abstract, timeless lessons?

MK: A big part of the reason why we did this book is because we found the love lessons in the great books so timeless. I write about Virgil's "Aeneid," and the relationship between Aeneas and Dido -- which was basically a friendship with benefits, or at least Aeneas thought it was, whereas Dido was a lot more invested. Rereading her story as I was working on the book, I was reminded of how amazingly contemporary it felt. And even with Jane Austen -- even with books written during an era when courtship was so much more formal -- there's a lot of philandering and a lot of wondering about where relationships are going that feels familiar. Maybe even more, with Austen, there are questions about finding the person who will help you become your true self, and your best self -- about self-realization -- which feel very relevant.

JM: Yeah, once you start talking about all-time classic books, they almost invariably have a level of depth and nuance that goes way beyond mere idealization. In fact, quite a few of the novels we cover dramatize the dangers of having rose-colored glasses on ("Great Expectations," "The Magic Mountain," "Remembrance of Things Past," etc.), so I’d say great literature actually helps you keep from living only in dreams.

Roughly how many of the lessons you discuss represent genuine revelations you had while reading particular books -- and how many represent the recognition of particular phenomena from your own life (or your friends') in great novels?

MK: In my case, just about all of them, really! That was another big impetus for the book; so many of the novels that Jack and I love had stories that resembled the ones we were hearing about from our friends, or the stories we've personally lived. When we were working on the book, my editor called me to say she'd been counseling a friend through a breakup -- and that she'd given the friend my chapter on "Revolutionary Road" because it was exactly what she needed to hear. It's about how to deal when you're dating a person who thinks he's meant for much better things -- but he's never had the courage to see if he can achieve those things. So he marinates himself in a bitter juice of self-importance, protecting himself from the truth about his own insignificance by telling himself how much better he is than everyone around him. "Howards End" also really spoke to me personally -- a book about what you should do if you're dating someone whose political views you don't agree with!

JM: Yeah, I confess to having sent draft chapters of mine and Maura’s to friends in the last few months just so I wouldn’t have to tell them the whole argument in person. And, as I express in a number of my chapters, I’m still trying to implement in my own life lessons from the books (like not over-idealizing at the beginning), so I’m thinking about the various books and scenes all the time.

Shares