Part 1: Dakar, Senegal

Americans will pronounce it hypercorrectly, with the "a" sound too shortened. "D'Car." Sort of the way they say "Khaaan" instead of "Can" when referring to that certain city in France.

The Senegalese say it more forcefully and flatter, both syllables equally stressed: "Dackkar."

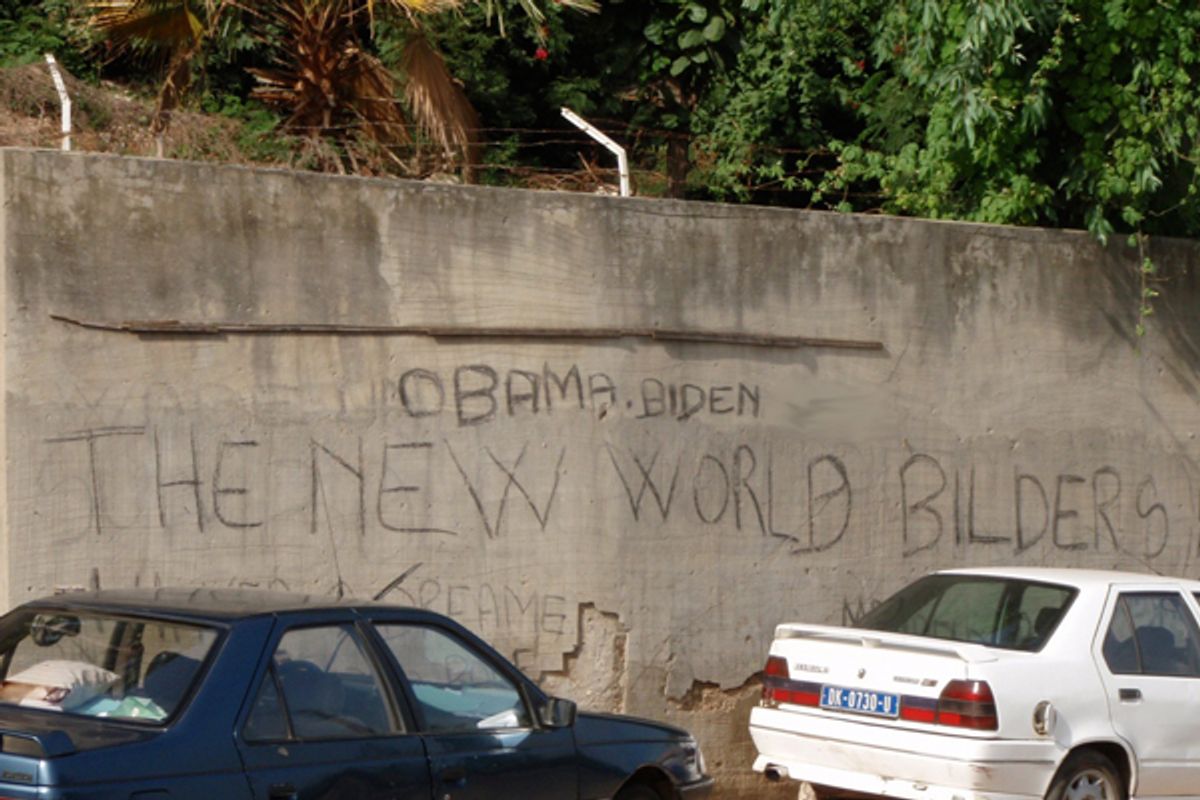

There used to be graffiti here, scratched out in what looked like charcoal, on a concrete wall behind the Pullman Hotel. "OBAMA, BIDEN," it said. "THE NEW WORLD BILDERS [sic]" You can see it above.

This was just before the election in 2008, when so much of the world, it seemed, was looking at America with a renewed sense of optimism and expectation. "Hope" was the big word, if I remember right.

That fever has passed. And the graffiti is gone now, blotted away with gray paint.

I pass that wall on my way to dinner at La Layal, the Lebanese place I'm known to frequent.

It's important, see, not to eat at the Pullman, where the surly poolside waitress might, eventually, bring you the pizza you ordered 90 minutes ago, and where the room service menu offers such delectables as:

Chief Salad

Roasted Beef Joint on Crusty Polenta

The Cash of The Day

Paving Stone of Thiof and Aromatic Virgin Sauce

That last one ... it sounds like the chapter from a fantasy novel. So it's off to La Layal, where once you get past the Testicles With Garlic and Lemon, or the Homos with Chopped Meat, the menu is both coherent and tasty.

They've gotten around, those Lebanese. Is there a city in the world, I wonder, that doesn't have a decent Lebanese restaurant or a Lebanese-run hotel?

The national dish of Senegal, though, is yassa poulet -- lemon chicken and onions served over rice. You can find it pretty much anywhere for hardly a few francs.

The beer here is called Flag. It's your basic warm-climate lager, drinkable and entirely unexceptional, though I prefer the Ghanaian version, Star.

I'm dining alone. My colleague on this trip is one of those pilots who tends to feel uneasy in certain parts of the world. He brings his own food -- bags of trail mix and cans of soup -- and stays in his room.

I enjoy the flight into Dakar. The way the Cap Vert peninsula appears on the radar screen, perfectly contoured like some great rocky fish hook -- the western-most tip of the continent, and the sense of arrival and discovery it evokes. There it is! Africa!

And in the evenings, the raptors, hundreds at a time in immense black flocks, spiraling over the concrete high-rises.

Yet it's also true that the more time I've spent in Senegal, the less I've come to like it. The country has a way of beating you down, sucking your faith away. The heat, the garbage, the pickpockets and hustlers.

Everybody hitting you up for something. Nobody smiling.

This is one of those places where you will see, right there in front of you, how the world is falling to pieces, its resources ravaged, the landscapes strewn with plastic. And there is little that you, as the Western observer, with or without your good conscience, are going to do about it.

They're spending billions on a new airport while the literacy rate hovers near 30 percent.

I come out of Layal tonight and give my leftovers to one of the city's uncountable urchins. The kid is 6 or 7, barefoot, begging with a tomato can. "Talibe," these vagrant boys are called.

He takes the bag without looking at me. No acknowledgment; not a glimmer of thanks. He grabs it the way a stray dog might grab a pork chop out of your hand.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Part 2

The bus leaves the hotel at 3 o'clock in the morning.

Somebody brought tuna for the airport cat, but nothing for the kids demanding money and ballpoint pens. Cadeau? Cadeau?

A truck follows us to the runway, to keep any stowaways from clambering into the gear wells.

The runway is long but poorly lit. There's something almost scary about it; turning into position and staring into those two skinny miles of oily blackness. Funny this was once a stop for the Air France Concorde.

Eastbound over Senegal, crossing into Mali. Predawn plumb-light, then sunrise. A hot red sphere balanced perfectly on a razor-straight horizon; the River Niger like a mirrored snake casting itself across the sahel.

Over the sewer-gutter town of Mopti, where I spent two days in 2002 on the way to Timbuktu. It looks so placid from 33,000 feet. I remember the riverfront trash, the shattered boats and the heaps of firewood raided from the forest. Naked children splashing in the greasy water.

The Bandiagara Escarpment is next. Home of the Dogon people, though you can't see them from a 767. I was there, too. We camped out.

The land below is the exact texture of 40-grade sandpaper, splattered with gray-green turds that turn out to be small villages. Each is a tiny star with red clay roads radiating outward.

I remember a New Year's Eve, on this same run, and midnight over the capital city of Bamako. The fireworks erupting below. Tiny points of light like fireflies. Tens of thousands of homemade incendiaries. Bamako's party looked like war.

Burkina Faso now. "Upper Volta" they used to call it, a name we found hilarious in seventh grade.

I wanted to be a pilot then.

Into northern Ghana. The controllers are friendly and polite, their instructions calm and measured.

The same can't be said for Kano, welcome to Nigeria. Say again? Repeat, please, Kano? Please? Say again? Over? Their voices are so angry and uncooperative that you want to turn around and fly home, like a dog retreating from a scolding.

The drive into town takes an hour.

The topography is vaguely prehistoric -- everything rendered a deep, almost putrefied green, with insanely jutting karsts reminiscent of Vietnam or the south of Thailand. The trees are clumped and gnarled. Goats, no dinosaurs.

The man sitting next to the driver has an AK-47 and a Kevlar vest. He turns around and smiles.

We tip him well.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

For more from West Africa, see Patrick Smith's Senegal YouTube video from Senegal, parts one and two.

Shares