No matter how he fares in South Carolina or Florida or wherever, Ron Paul is going to take his presidential campaign all the way to the Republican convention this summer. He won't be close to the 1,144 needed to claim the nomination, but he does figure to arrive in Tampa with a bloc of several hundred delegates.

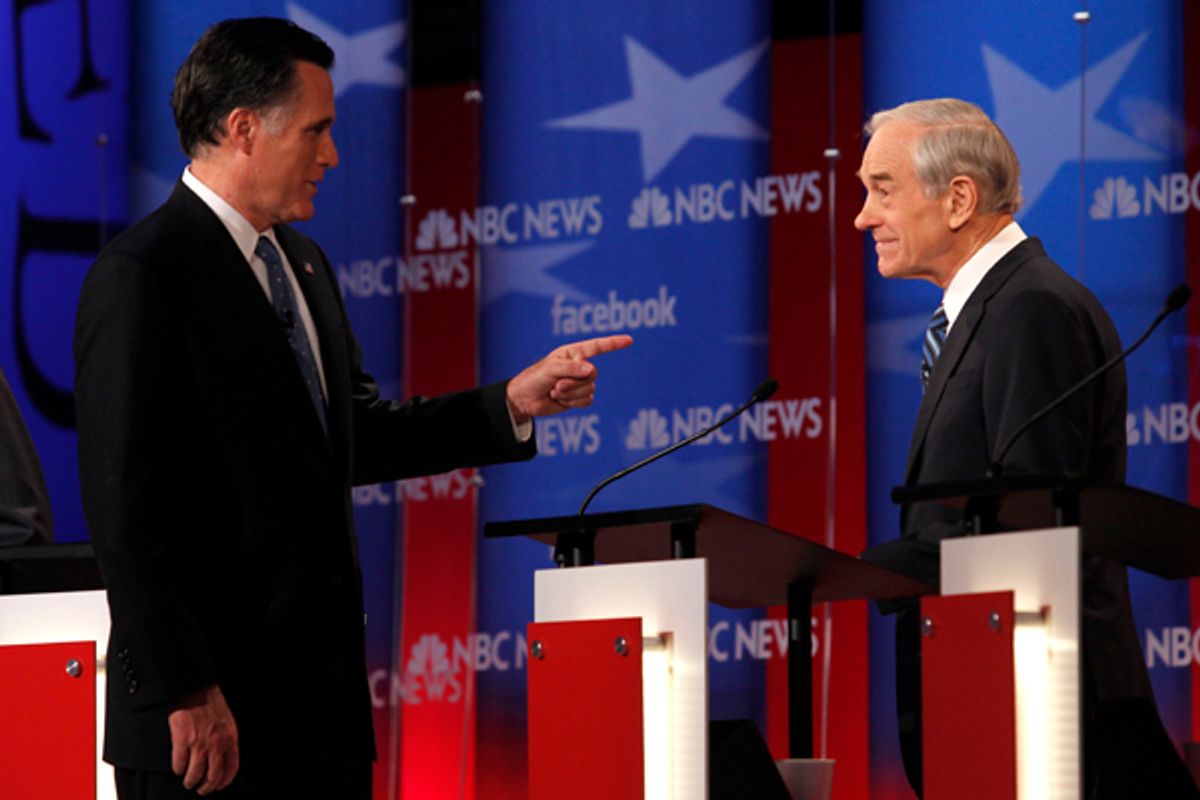

This likelihood is making some who don't share his views apprehensive, a sentiment that the Forward's J.J. Goldberg encourages in a new column. Goldberg argues that Paul, who earned a handful of delegates in Iowa and New Hampshire and could pick up a lot more in a series of small and mid-size state caucuses next month, is poised to use his "unexpected measure of clout" to pull the nominee toward his foreign policy views, particularly on Israel. As Goldberg sees it, Mitt Romney will keep winning primaries and lock down the nomination but will then need to deal with Paul and his delegates (with the added threat of a third-party Paul campaign hanging in the air):

In other words, Romney will need to appease Paul with platform planks and perhaps promises of administration positions for his allies. A stronger Romney could simply ignore Paul’s surge. But Romney isn’t strong.

To be sure, Paul supporters are just as excited about this possibility as Goldberg and others are nervous about it. But the reality is that Paul probably won't end up with anywhere near this level of influence.

There are several reasons for this. The first deals with the mechanics of the convention. As Jonathan Bernstein explained recently, it's very likely that the GOP race will soon produce an "inevitable" nominee (presumably Romney), prompting every other candidate except Paul to withdraw and allowing Romney to skate through the rest of the spring months by racking up lopsided primary victories over Paul. Romney would then arrive at the convention with the vast majority of delegates committed to him and wouldn't actually need Paul's delegates for anything.

Of course, even if he has the votes to keep Paul from shaping the platform, it might be in Romney's interest to deal with him anyway, in an effort to make himself more appealing to Paul's army. But there are limits on what it would be wise for Romney to do. The key is that Romney would not give in on any major issue on which Paul's position is at odds with the party's base.

In this way, Romney would actually be a very strong nominee, because while many key leaders on the right aren't wild about him, they do care deeply about (for instance) preventing Paul's Middle East views from becoming party orthodoxy. They'd have Romney's back in any showdown with Paul -- and they'd be bitterly disappointed if Romney gave an inch. So while appeasing Paul on any of the issues that separate him from the GOP mainstream might help Romney win him over for the fall, it would also set back Romney's efforts to energize the much broader conservative GOP base. Maybe Paul will get a tough anti-Fed plank in the platform, but when it comes to Israel, Iran, foreign policy in general, the drug war and civil liberties any platform fight wouldn't just be between Paul and Romney -- it would be between Paul and the rest of the GOP.

Perhaps a more interesting question is what kind of speaking role Paul will receive. Will he be showcased in prime time, forced into an early evening slot that only C-Span will show, or snubbed altogether? I wrote earlier this week that his campaign is akin to those of Pat Buchanan, Jesse Jackson and other "cause" candidates who built devoted followings and won significant numbers of delegates while being unacceptable to the majority of their party. Their convention treatments varied:

Jesse Jackson, 1984 and 1988: Jackson, the first African-American to wage a full-scale nationwide campaign, was given a prime-time convention speaking role after both of his campaigns. His mesmerizing '84 address in San Francisco ("God is not finished with me yet") built excitement for his follow-up campaign four years later, when he doubled his vote total and briefly seemed to have a chance of winning the nomination (at which point party elites undermined and marginalized him). At the end of that '88 race, in which Jackson won 7 million votes, he argued that he had earned the No. 2 slot on the ticket with Michael Dukakis, but Dukakis never seriously considered him for the role. Because Jackson established himself as the face of a hugely important demographic group within the party, it was impossible for party leaders to snub him at both conventions, even if negotiations beforehand were ugly.

Pat Robertson, 1988: He suspended his campaign in May 1988, as George H.W. Bush was rolling to the nomination, but held onto his delegates in a bid for convention leverage. But the Bush campaign was in an accommodating mood. To gain the nomination, Bush had spent the previous eight years refashioning himself as a Reagan-style conservative, after running as a moderate (pro-choice, pro-ERA, anti-supply side) against Reagan in the 1980 primaries. The right remained suspicious (just like today with Romney) and the Bush campaign wanted no problems at the New Orleans convention, where Robertson was given a major speaking slot and where a platform just as conservative as Reagan's from 1984 was ratified without incident.

Jerry Brown, 1992: After disappearing for most of the 1980s, Brown reemerged in late 1991 to launch a third presidential bid, this time running as populist insurgent who refused checks of more than $100 and relentlessly bashed the influence of Wall Street, big business and wealthy donors in Democratic politics. In the early contest, Brown struggled to stand out and Bill Clinton emerged as the seemingly inevitable nominee. But then, with the rest of the field cleared, Brown pulled off a shocking upset in the Connecticut primary, kicking off a bitter two-week campaign in New York, with party leaders hinting they'd draft a new candidate into the race if Clinton lost again. Clinton survived, though, and then won lopsided victories in every remaining contest, but Brown stuck around and arrived at the New York convention with about 600 delegates. He demanded a prime-time speaking slot and was told he'd need to endorse Clinton first. Brown refused and instead had his delegates (who spent much of the convention chanting, "Let Jerry speak!") place his name into nomination, a move that forced convention organizers to give Brown 20 minutes at the podium. It wasn't a complete victory for either side: Brown got to speak (and didn't mention Clinton), but he delivered his remarks well before prime time.

Pat Buchanan, 1992: George H.W. Bush was even more desperate to appease the right in '92 than he had been in '88 -- a result of the GOP civil war triggered by his decision to go back on his "Read my lips!" anti-tax pledge. That, along with several other breaks with conservative orthodoxy, convinced many conservatives that they'd been conned in '88 and that Bush was, at heart, the moderate Yankee Republican he'd run as in '80. This gave rise to a primary challenge from Pat Buchanan, who humiliated Bush with a strong showing in the lead-off New Hampshire primary. Buchanan never performed as well in any other state, but he did accumulate more than 3 million votes and arrived at the convention with about 150 delegates. Technically, this didn't give him much clout, but Bush was desperate to unite the party, so Buchanan was handed the featured speaking slot on the first night and used it to deliver his infamous "culture war" speech -- and to knock Ronald Reagan, who followed him at the podium, out of prime time.

Pat Buchanan, 1996: The hostile reaction to the "culture war" speech (and to the right-wing tone of the '92 convention in general) convinced party leaders that they'd gone too far in appeasing the right and had scared off swing voters. So even though Buchanan did even better in his '96 campaign (even winning New Hampshire) and brought a bigger "Buchanan brigade" to San Diego, Bob Dole's campaign refused to give him a formal speaking slot, not even in a non-prime-time hour. They wanted the television coverage to be dominated by moderate, swing voter-friendly faces (Colin Powell, for instance) and offered Buchanan only a chance to appear with all of the other defeated primary candidates in a pre-taped video that would air during the convention. He refused, rented his own hall across town, and delivered a speech there instead. But he didn't bolt the party (that would happen three years later) and his delegates didn't go through with a threatened walkout during Dole's acceptance speech.

Shares