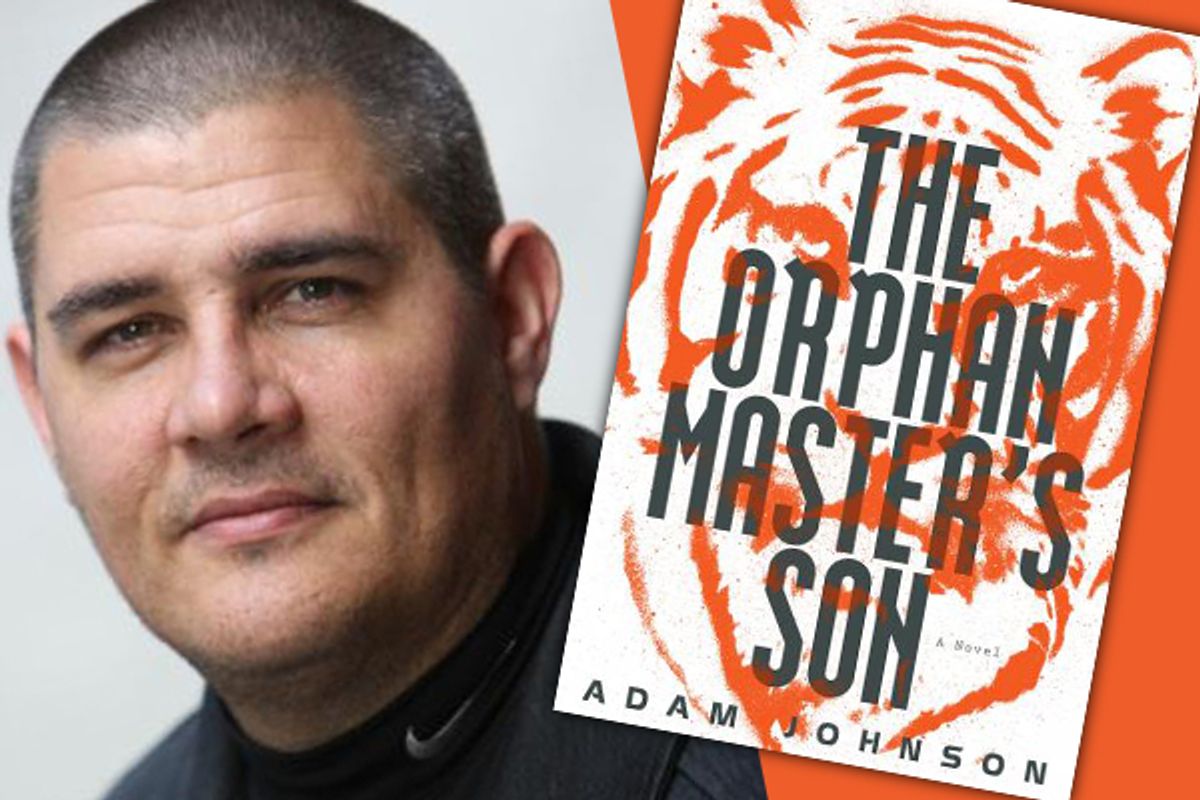

"In North Korea, you weren't born, you were made," muses a character in Adam Johnson's momentous new novel, "The Orphan Master's Son." It's a book that inevitably brings to mind George Orwell's "1984," but while Orwell's novel is as tight and focused as a parable, "The Orphan Master's Son" ranges from the bottom of North Korea's social ladder to its top, with plenty of affecting, wayward and even comic supporting characters. It's the horror and absurdity of life in a totalitarian state as it might have been depicted by Balzac.

The character who takes the reader on this wrenching journey and gives the book its title, Jun Do, is not an orphan despite having grown up in an orphanage in the provincial town of Chongjin. His mother -- a beautiful singer who, like all beautiful women, we are told, got "shipped off to Pyongyang" -- is simply gone, leaving his father, the Orphan Master, a devastated and none-to-compassionate man. The orphans, like the beautiful women, are little more than a commodity (if a far less valuable one), and are sold off to work at hazardous factory jobs. The resourceful Jun Do survives this Dickensian situation and lands in the army. First, he learns to fight in the pitch-dark tunnels under the border with South Korea. Then he becomes part of a seagoing team of military kidnappers who specialize in abducting foreigners with desirable talents from beaches and piers.

In the course of the novel's first half, Jun Do will go from unwanted urchin to ad hoc envoy by way of a surveillance station concealed on a fishing boat. He even finds himself in Texas for a few days, acting as translator for a government minister (who's actually a driver pretending to be the minister). But wherever he is, Jun Do's fate is precarious. At any moment, anybody's life can take a catastrophic turn. If your shipmate defects, the rest of the crew gets sent to prison camps. If your boat gets boarded by a bunch of frisky American soldiers and they make off with your obligatory photograph of Dear Leader Kim Jong Il as a souvenir, you get sent to a prison camp. If you fail in the daft diplomatic mission to which you have been detailed, you get sent to a prison camp. If you manage to avoid the prison camps long enough to grow old, the regime will supposedly send you to a retirement village on a famously beautiful beach, but when Jun Do's ship cruises past the area one day, its white sands are ominously empty.

You can probably guess where Jun Do ends up, and then, roughly in the novel's middle, the book switches from a straightforward, third-person narrative to a braid of very different voices. There's a variation on the jingoistic broadcasts every North Korean citizen is forced to listen to from dawn to dusk and the first-person recollections of a nameless interrogator trying to crack a particularly tough case. The interrogator's subject has brazenly impersonated a celebrated national hero (and possible rival of the Dear Leader) to the extent of moving in with the man's wife, North Korea's most beloved movie star.

The impostor is Jun Do -- and he isn't. "For us," a seasoned operator tells Jun Do before his transformation, "the story is more important than the person. If a man and his story are in conflict, it is the man who must change." Since the Dear Leader chooses to behave as if the impostor really is Commander Ga, then, for the time being, that's who he is. The novel itself becomes a maze of false fronts and hidden truths -- the very stuff of survival in a society based on deprivation, arbitrary cruelty and lies.

"There is a talk that every father has with his son," explains the interrogator, "in which he brings the child to understand that there are ways we must act, things we must say, but inside, we are still us, we are family ... We must act alone on the outside, while on the inside, we would be holding hands." If I ever have to denounce you or you have to denounce me, the man is saying, remember that it's not the real you or me who does this.

The forlorn hope that love can persist in such circumstances is belied by the interrogator's own parents, who fear him and never speak an unguarded word in his presence. He becomes fascinated with "Commander Ga," who seems to have found genuine love with the actress. Meanwhile, the loudspeaker voice carries on, spinning yet another version of the novel's events, full of all the preposterous propaganda of a dictatorship built around a cult of personality. Is it even possible to possess an identity -- let alone to know intimacy -- in such a world, where everyone is desperately pretending to be what everyone else knows they are not? A world where, with the slightest misstep, the people you love can be swallowed up by the gulag, disappearing forever? The first time Jun Do sees an American telephone book he's dumbstruck at the realization that "you could look up anyone and seek them out."

Although "The Orphan Master's Son" spins itself into a web of uncertainties, the novel never scatters, meanders or lapses into arty opacity. Johnson makes a story about the instability of stories into an impressively coherent and arresting narrative. The main character, whoever he is, moves ever closer to true selfhood, which is, for him, the equivalent of doom; yet it's a joyful doom, as strange as that may sound. From peripheral sources, it's clear that Johnson spent years on the research for this novel -- which extended to a trip to North Korea itself -- and this shows in the fine texture of his observation. But the real marvel of "The Orphan Master's Son" is its imaginative depth and breadth, something that absolutely can't be faked. Which may be why there are no real novelists in North Korea.

Shares