BOSTON—If there’s a lonely glimmer of hope in the gloom and doom over money in politics, it was born this week in Boston with the signing of the People’s Pledge agreement to extinguish the onslaught of SuperPac ads polluting the Massachusetts airwaves, ten months before the nation’s most closely watched Senate race comes to an end.

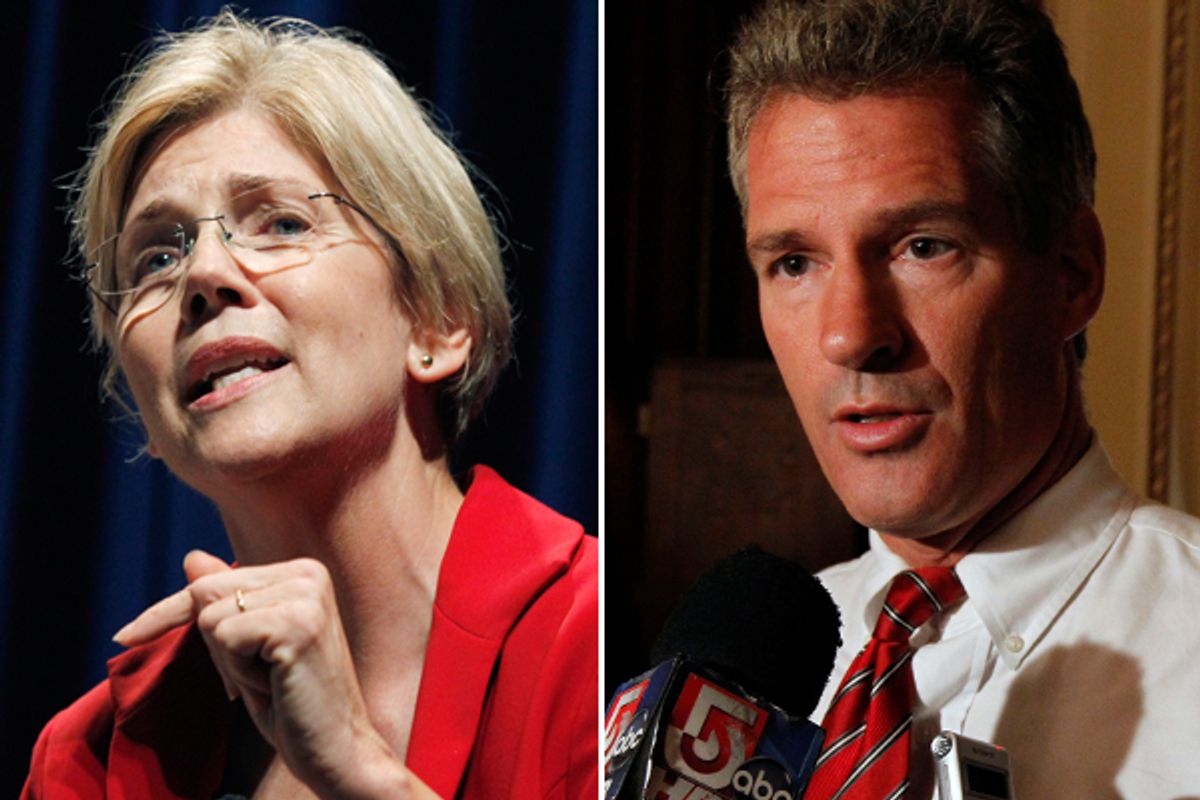

The brainchild of Harvard Professor Elizabeth Warren, the darling of the left—yet prompted by Senator Scott Brown, the Tea Party centerfold who took Ted Kennedy's seat—the key enforcement mechanism is remarkably simple in its conception: the candidate favored in a third-party ad on TV, radio or online must make a contribution worth half of the ad’s costs to the opposing candidate’s charity of choice within three days of broadcast.

The negative air war that was predicted two years ago as a consequence of the Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling could very well be thwarted in this one key race. It’s the little engine that could, nationally, but if the Massachusetts experiment in self-punishment proves enforceable here, it could catch on elsewhere, sort of like the Pledge of Allegiance against dirty politics, a yardstick that blunts the worst consequences of the high court’s decision.

Or it may prove to be a campaign game changer only in a blue state like Massachusetts where an incumbent Republican is covering his left flank with a clean-money pledge. In red states where there’s a Democratic incumbent, say, the People’s Pledge is much less likely to take root.

Warren, the less-well-known newcomer who needs to do more flesh-pressing to win over undecided voters, may benefit more from the pact than Brown, who took the late great lion of the Senate’s seat in a stunning upset runoff election in 2010. It was Brown's camp that came up with the idea, and Warren, personally, who gave it teeth, essential enforcement mechanisms being a forte that would seem to separate this woman from the boys on Capitol Hill, should she take back Brown’s Senate seat for the Democrats.

The People's Pledge is most likely to rise or fall with her political fortunes, which is to say its potential is every bit as promising as the smart money’s long-shot favorite to be our first female president. A regular on the Daily Show With Jon Stewart, where she re-appeared last night as her apple-cheeked, all-American self, looking professorial, but without the affected demeanor, Warren comes across as the down-to-earth daughter of, as she told Stuart, “a guy who sold fencing.” Warren went on to give a little history lesson about the 1940s, when she was born, when the government went to bat for the middle class, the same government that today goes to bat almost exclusively for the 35,000 lobbyists that swarm the halls of power

The deal, signed by both candidates, will be watched by none more closely than the shadowy, big-money SuperPacs that have hijacked the 2012 election season. Above all else that means Karl Rove and the Koch brothers who back his billionaire front group, the American Crossroads GPS think tank, which has already sunk more than $1 million into the Brown-Warren contest.

Rove may be pleased to know that not one Boston radio or television outlet has agreed to comply—it’s business after all and, as Ronald Reagan said, the politics of America is business—though they will feel nearly irresistible pressure to do so over the next few days as both campaigns mail a co-letter asking media outlets to forgo what amounts to a nice chunk of change for the local market.

The liberal League of Conservation Voters, which just bought a $2 million ad buy against Brown, said it would honor the deal Still there was a muted response in the blogosphere, a place normally divided over the wisdom of grotesque sums being spent on vulgar attack ads. The truce was noted widely if dispassionately. Daily Kos merely observed that the campaigns had swapped letters about the sums being spent already. The site noted that Brown had called on Warren to condemn the ads, and the Warren had responded last Friday with her idea to stand together beyond mere words. Brown accepted, the Daily Kos noted generously, even though the U.S. Chamber of Commerce had said it would become “significantly involved” in defeating his opponent.

Similarly, Talking Points Memo ran with a straight-up “we intend to comply” story quoting a Massachusetts Democratic Party official.

The muted response may be a consequence of the hardened skepticism about plugging the flow of SuperPac money. Sending letters to TV stations and advocacy groups asking them to curb the ads amounts to “an interesting and commendable effort,” said Paul Ryan, a lawyer for the Campaign Legal Center, which works on behalf of tighter campaign funding laws. “But I’m not entirely convinced it will be effective.”

Ryan said that issue ads, traditionally used to dodge limits on direct candidate advocacy, may blur the lines, complicating compliance.

Though no other group has come out against the pledge, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee and National Republican Senatorial Committee have not yet said if they’ll try to call off the dogs in their own parties.

All that can be said for sure is that populist politics appears ready to trump the billion-dollar campaign industry in at least one race in the cradle of liberty. But if the People’s Pledge really takes off in Massachusetts, putting your money where your SuperPac mouth is may be the only way to avoid wearing the dirty-money badge of shame. Best case scenario: In the era of Citizens United, the People's Pledge could yet become an unavoidable rite of American politics.

Shares