Barring a stunning turnaround in the next 24 hours, Newt Gingrich is going to lose the Florida primary, potentially by a very wide margin. Polls released over the weekend showed him falling behind Mitt Romney by margins of eight, 11, 15 and 16 points, suggesting that Gingrich’s slide in the middle of last week accelerated in the wake of his dismal Thursday night debate performance.

Not surprisingly, the former House speaker is already trying to spin away the significance of a lopsided Tuesday defeat. He’s vowing to stay in the race through the convention and playing up his lead – and Romney’s modest level of support – in national tracking polls.

“You just had two national polls that show me ahead,” Gingrich said over the weekend. “Why don't you ask Governor Romney what he will do if he loses since he is behind in both national polls?'

His statement is true enough. As of Sunday afternoon, Gallup’s daily numbers gave him a 28 to 26 percent edge over Romney, and other national surveys over the past week have put him up even more. But Gingrich is suggesting that this means the national momentum is on his side (“We are pulling away from him,” he said Sunday) and that taking a hit in Florida won’t slow him down, and here there’s reason to be very skeptical.

For one thing, Gallup’s Sunday data actually indicated that Gingrich’s lead had slipped by four points over the previous 24 hours (he was up 32-26 percent on Saturday) – not that he was “pulling away” from Romney. It’s likely that the abuse Gingrich has taken from the Romney forces and from many opinion-shaping Republican voices over the past week is taking a toll at the national level, too – just not as dramatically as in Florida, where the abuse is also being doled out in 30-second attacks ads. Within a few days, Gingrich may not have a national lead to brag about.

This is especially true when you consider the likely impact of a clear Romney win in Florida, which would dominate political headlines and re-establish a Romney-as-inevitable-nominee press narrative. We saw this happen earlier this month, when Romney posted a microscopic victory in Iowa* and a solid victory in what is essentially his home state – two feats that might not have seemed very impressive but that nonetheless sent his national support soaring to new heights. Romney’s supposed 25 percent national ceiling was a dominant theme for all of 2011, but by the middle of this month Gallup had him nearing 40 percent, and opening a 23-point lead over his nearest foes. Expect something similar if the story coming of Tuesday night is: Romney wins big.

Granted, Gingrich can draw hope from what happened after Iowa and New Hampshire, when he caught fire in South Carolina, recaptured the right’s imagination, and parlayed the momentum into the national lead he’s now pointing to. It’s been a zany enough GOP race that the possibility of Gingrich retrenching in a post-Florida state and recreating this magic can’t be excluded, especially with most of the Old Confederacy yet to vote. (For that matter, there’s also the possibility that he’ll defy the current trends and fare much better in Florida than everyone now expects.) And the fact that so many national Republican voters were so quick to abandon Romney when Gingrich made his South Carolina move is yet another reminder of what a weak front-runner Romney has been throughout this entire campaign.

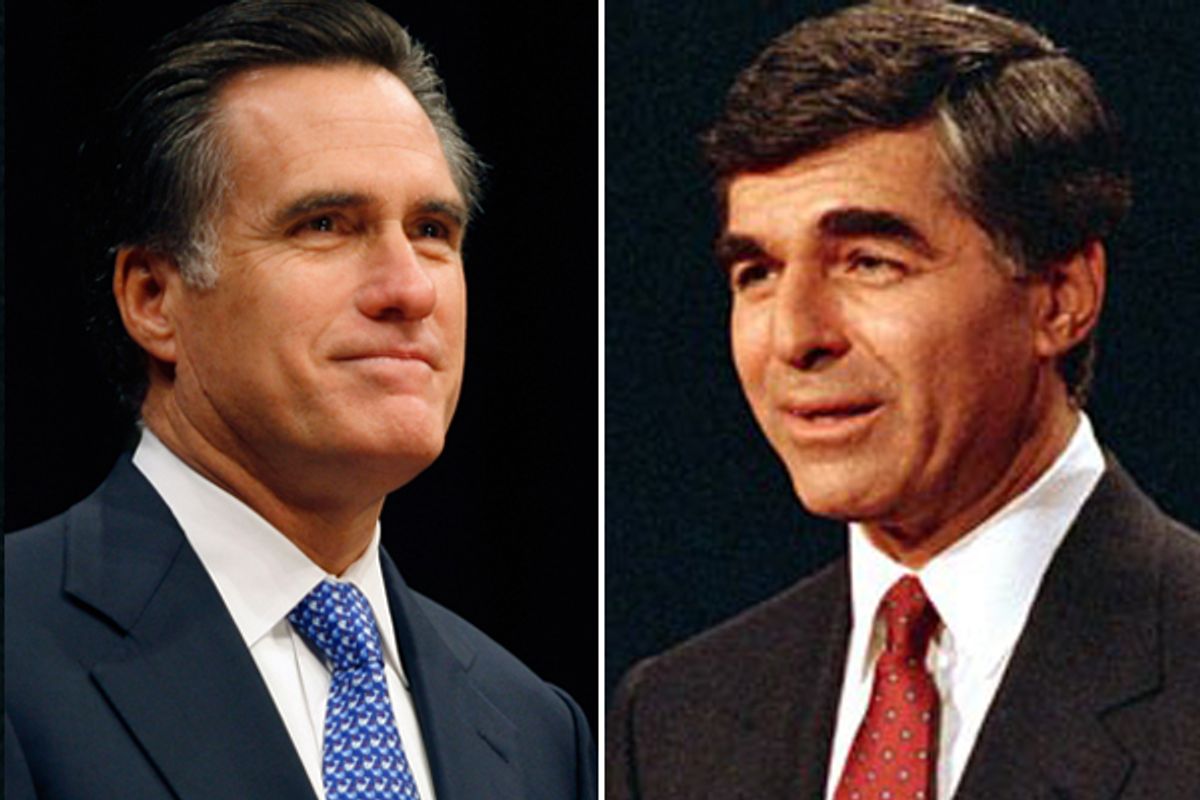

But the longer this process goes on, the more Romney’s struggles call to mind those faced by another major party nominee from his home state: Michael Dukakis. Obviously, this isn’t a comparison the Romney campaign would care to embrace, but Dukakis’ slow and painful march to his party’s 1988 nomination should be a source of some optimism for them.

Like Romney, Dukakis was an unusually vulnerable front-runner in a race defined by some wild polling fluctuations. Even when he broke through with some early successes, Dukakis had an excruciating time running away with the race. He endured several shocking and embarrassing setbacks in key primary tests, results that cast doubt on his viability and stoked the kind of deadlocked convention talk we’re now hearing in connection with the GOP race. Well after Iowa and New Hampshire, he found himself polling under 30 percent in the national horserace.

Dukakis’ problems stemmed from his status as an accidental frontrunner. The campaign began with Gary Hart as the overwhelming favorite, but Hart quickly crashed in a sex scandal. Dukakis caught another break when Joe Biden, who demonstrated real potential in the spring and summer of 1987, dropped out in another scandal (in which Dukakis’ campaign manager played a crucial role). By the end of ’87, Dukakis was generally seen as the party’s most likely nominee, but his national support lagged. He then finished respectably in Iowa, prevailed easily in New Hampshire, and won some big states (Texas and Florida) on Super Tuesday. This was enough to put him in first place nationally, but with only 29 percent.

And then the bottom almost fell out, when Dukakis finished a distant third in Illinois (behind favorite son Paul Simon and Jesse Jackson) and was crushed by Jackson in Michigan. The latter result gave Jackson a slight lead in the national delegate race – and sent the party’s establishment into a panic. They closed ranks behind Dukakis and worked to marginalize Jackson, and it paid off with clear Dukakis victories in Wisconsin, Connecticut and New York. That vaulted Dukakis into the clear national lead that had eluded him, and he was never seriously challenged the rest of the way.

There were two keys to this for Dukakis. One was that he was always a broadly acceptable nominee for his party: Polls consistently gave him high favorable scores among Democratic voters, who also indicated to pollsters that they didn’t consider Dukakis uniquely objectionable among their primary season choices. The other was Jackson’s emergence as his chief rival and a (seemingly) serious threat to win the nomination, which gave party leaders and opinion-shapers an urgent reason to rally around Dukakis.

Those two factors seem to be at work in the current GOP race. For all of the talk of the party base’s resistance to Romney, he’s consistently racked up strong favorable and “acceptability” scores among Republican voters. And as his post-Iowa/New Hampshire bounce showed, there are circumstances under which national Republicans will move his way in big numbers; the 25 percent ceiling doesn't really exist. Romney may not be the dream choice of the average Republican, but he can be an acceptable choice. And Gingrich clearly unnerves GOP elites, who have tended to react to his South Carolina victory with the same panic that marked the Democratic response to Jackson’s Michigan landslide 24 years ago.

The GOP calendar seems to set up favorably for Romney after Florida, with a series of winnable contests in February followed by Super Tuesday in early March. This race has been wild enough that another Gingrich surge remains possible, even if he does lose Florida badly. But it's also a good bet that the GOP elites who've been bashing him for the past week won't let up this time (like they did after Iowa and New Hampshire). And the more successive victories Romney posts, the more inevitable his nomination will seem.

So while it’s true that his national support isn’t much to write home about now, Romney may actually be in position for the same kind of nomination-clinching roll that Dukakis enjoyed just after his candidacy hit bottom.

Shares