Most thrillers do not send me hustling off to Wikipedia for a refresher course in the Stoic philosophy of the first century A.D. Greek sage Epictetus. But that's where I found myself before commencing this review of "The Fear Index," by Robert Harris. I wanted to be sure I was properly grounded before straying into treacherous territory: the nature of being in our phantasmagorical high-finance, high-tech era.

I certainly had no time to brush up while actually reading the novel. "The Fear Index" is a perfect exemplar of the species "taut thriller." It's a book whose pages cannot be turned fast enough; a mystery with just a dash of science fiction and plot twists ripped from the business news headlines of the past year. Beware taking this book to bed with you, because you will stay up too late. (And your dreams will be queasy.)

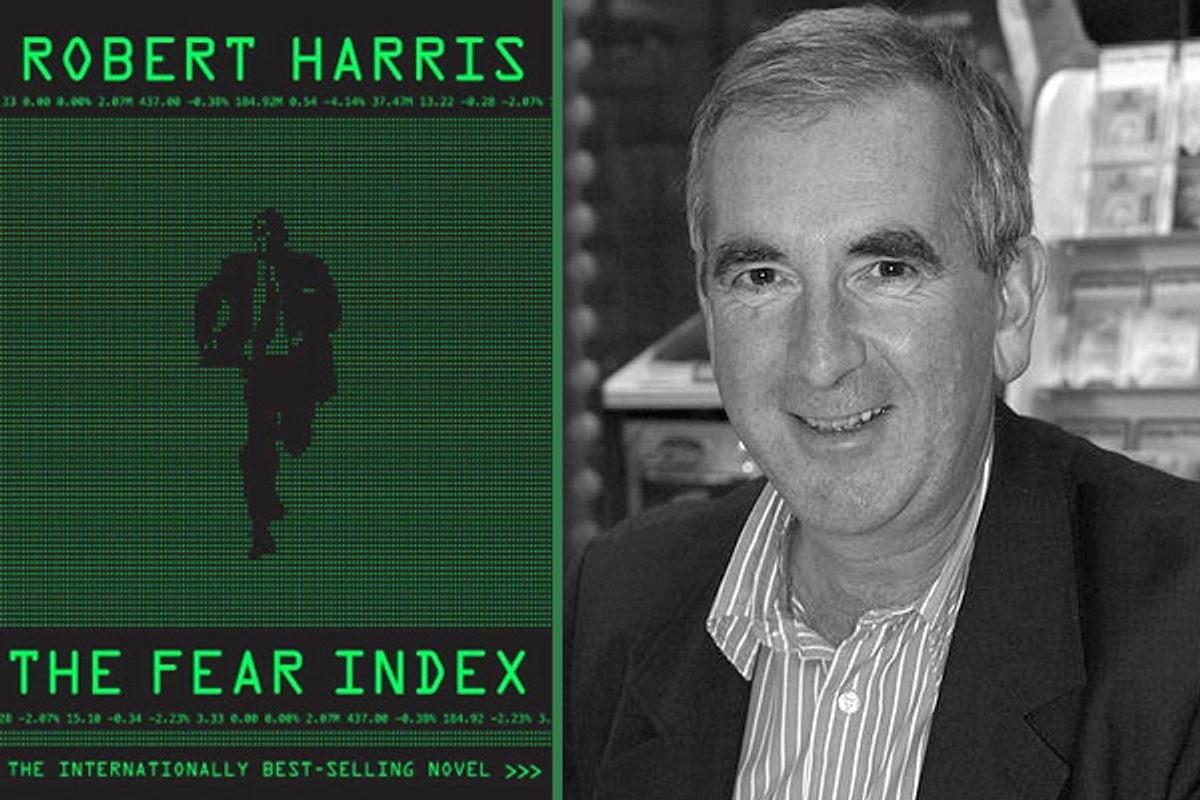

But in the haste to turn those pages lies a danger: the chance that you might miss how surprisingly profound "The Fear Index" is, in its contemplation of modern financial markets and the "digitalization" of modern life. With his previous novelistic excursions to ancient Rome ("Pompeii," "Imperium"), and reimaginings of history ("Fatherland" -- set in a Germany where Hitler won World War II), Robert Harris long ago proved himself capable of mixing high intelligence with action and a swiftly moving movie-script-ready plot. "The Fear Index" takes his game to the next level: It is a riveting meditation on the reality of now, complete with a trail of bodies and streaks of madness -- both algorithmic and human.

Which brings us back to Epictetus. The heart of "The Fear Index" is the story of how a hedge fund's attempts to generate unprecedentedly huge financial returns from stock market bets executed by a super-smart computer program go horribly wrong. (Sound familiar? Didn't we just live through that?) The program is the brainchild of physicist Alexander Hoffmann, and the key to its successful operation is its ability to sniff out traces of fear in the markets. Where there's fear, there's volatility, and where's there volatility, there is the opportunity to cash in.

About a third of the way through the novel, Hoffmann explains to a group of prospective investors (the 1 percent of the global 1 percent!) that the times are ripe for a trading strategy based on fear, because contemporary society has never been so fearful, a fact for which we can blame our online, networked lives.

"Our conclusion is that digitalization itself is creating an epidemic of fear, and that Epictetus had it right: we live in a world not of real things but of opinion and fantasy. The rise in market volatility, in our opinion, is a function of digitalization, which is exaggerating human mood swings by the unprecedented dissemination of information via the Internet."

Epictetus nailed it. The mood-swingingness of our universe is a truth apparent to anyone who follows the zigs and zags of modern financial markets (or the Republican primary race, for that matter). Computer-driven trading strategies are not reacting to fundamental economic realities; they're bouncing out buy and sell orders every nanosecond based on price shifts that are themselves generated by emotional reactions to news headlines. A German foreign minister says something nasty about Greece, and markets plunge as London, New York and Shanghai all freak out. Moments later, a soothing press from a central banker sends prices skyrocketing again.

It's a crazy way to run an economy. And it's not fiction. Harris underlines this point by interpolating into the plot actual testimony before Congress by current Securities Exchange Commission Chairwoman Mary Schapiro explaining the notorious "Flash Crash" of May 2010. On May 6, the Dow Jones industrial average fell 1,000 points in a matter of minutes before suddenly rebounding. Computers were largely to blame. More such shenanigans are on the way! It's a sign of how murky our digitally mediated markets are now, how inscrutable to human understanding, that science fiction offers just about as good an explanation of what is going on at the New York Stock Exchange as do the most highly paid market analysts.

Epictetus had it easy. We are no longer capable of understanding what we have wrought. That's a job only the algorithm can do.

More from Hoffmann:

"When Hugo and I started this fund, the data we used was entirely digitalized financial statistics: there was almost nothing else. But over the past couple of years a whole new galaxy of information has come within our reach. Pretty soon all the information in the world -- every tiny scrap of knowledge that humans possess, every little thought we've ever had that's been considered worth preserving over thousands of years -- all of it will be available digitally. Every road on earth has been mapped. Every building photographed. Everywhere we humans go, whatever we buy, whatever websites we look at, we leave a digital trail as clear as slug slime. And this data can be read, searched, and analyzed by computers and value extracted from it in ways we cannot even begin to conceive."

The most terrifying part of "The Fear Index" is the sinking sensation, as you turn the last page, that we haven't seen anything yet. We are incapable of comprehending the totality of the data we produce. We'll design ever more complex computer programs to do that for us. And they're going to make a big mess.

Shares