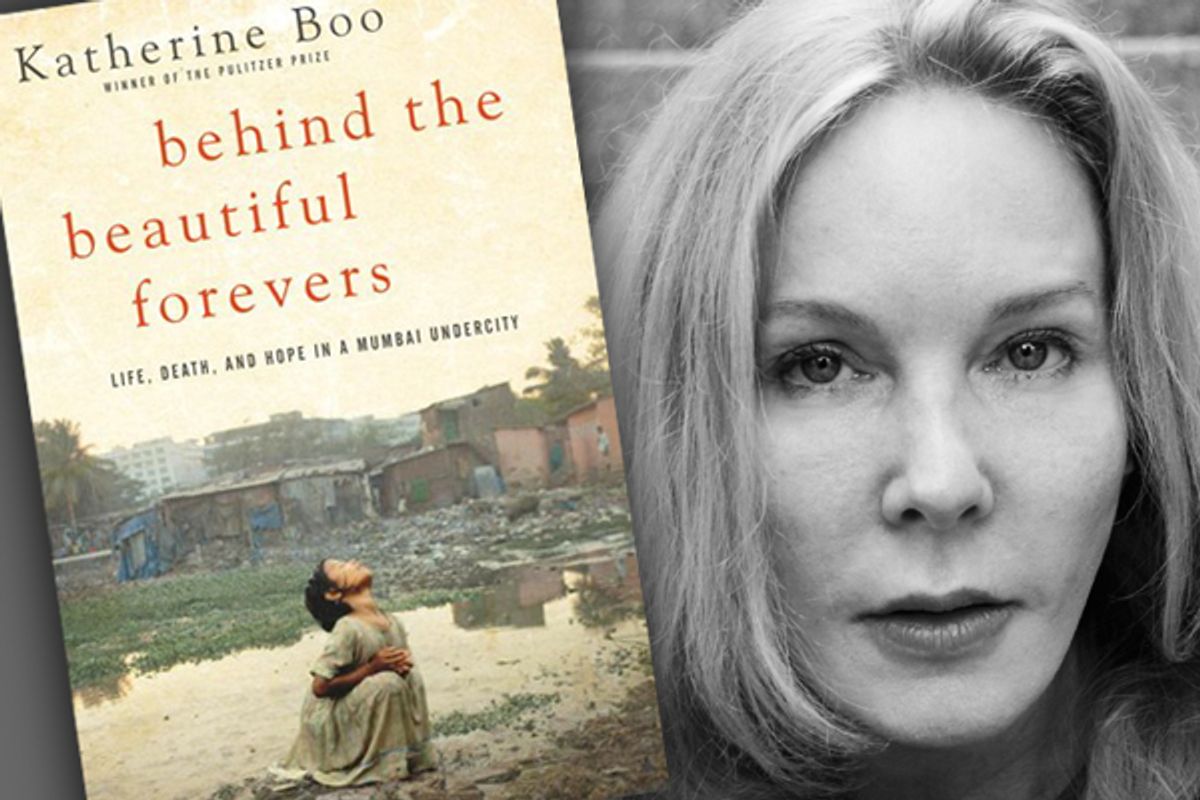

There are cult filmmakers and cult novelists, but Katherine Boo may be the world's only cult journalist. Although a recipient of the Pulitzer Prize and a MacArthur Fellowship, she's not a marquee name in her profession. Yet those discerning readers who have latched onto her work -- particularly her articles for the New Yorker -- are obsessed with it. (The TV and movie producer J.J. Abrams, of all people, once interrupted an interview to rhapsodize for 10 minutes about Boo. "Do you know her?" he asked reverently.) And now, at last, Boo has published her first book.

"Behind the Beautiful Forevers" is the result of intensive, immersive observation over the course of four years in the life of a Mumbai shantytown called Annawadi. Boo's technique is as exhaustive as it is self-effacing. She conducts countless hours of interviews with her key "characters," interviews that, to judge by the results, can be as searching as therapy sessions. She backs these up with documentary research and shoe leather reporting. To establish what actually happened during a crucial event -- the self-immolation of a one-legged woman following a dispute with one of the book's central families -- she interviewed 168 people, many of them more than once. She never mentions herself.

It's tempting to compare the resulting narrative, seamless and intimate, to a novel, but since the reading public appears to be allergic to fiction about people like the Annawadians -- poor, foreign and dark-skinned -- that would hardly do it justice. This is a scrupulously true story, and therefore comes to us with an added luster of authenticity. But unlike most reporting on the poor, foreign and dark-skinned, "Behind the Beautiful Forevers" mightily resists the urge to treat any of the half-dozen principle characters as examples of their class. The whole point of the book, as Boo states in an interview with her editor included as an afterword, "is to portray these individuals in their complexity -- allow them not to be Representative Poor Persons."

Who are they? Most of them are members of two families, each led by an indefatigable but flawed matriarch saddled with a weak spouse. The Husains are Muslims, migrants from northern India, who have built some modest security for themselves in the trash-picking trade, largely through the sharp eyes and diligence of the oldest son, Abdul. The other clan is Hindu and led by the formidable Asha, a ruthless fixer who aims to make herself the "slumlord" of Annawadi via her connection to the Hindu nationalist political party, Shiv Sena (a sort of Hindu Tea Party). Supporting characters include the bright and curious Sunil, a boy of indeterminate age, who sells his scavengings to Abdul.

Abdul is the quintessential head-down striver, while his brother Mirchi -- in whose education the family has sunk a lot of its resources -- dreams of "wearing a starched uniform and reporting to work at a luxury hotel" like the ones attached to the nearby international airport. For her part, Asha has raised a beautiful daughter, Manju, who promises to be the first female college graduate from Annawadi, though she's too tender-hearted for her mother's tastes and dreads being married off, as planned, to a boy from Asha's home village. Still, Manju's lucky compared to her spirited best friend, Meena, whose Dalit (untouchable) family beats her every time she presumes to question their orders or plans for her.

The Husains' fate takes a turn for the worse when they decide to spend some of their new disposable income on a tile floor for their shack. (The "Beautiful Forevers" of the book's title refers to a repeating ad for similar tiles, posted on the wall that screens off the slum from the airport road.) Their neighbor -- the one-legged, man-crazy and quarrelsome Fatima -- virulently objects to the noise, and the ensuing dispute ends with Fatima setting herself on fire after promising to "put you in a trap." In the hospital, she accuses the Husains: first of burning her, and then of compelling her to burn herself. The case plunges the family into the nightmare world of Indian law enforcement and jurisprudence.

The charge is ridiculous, but this system, which for several years consumes much of the family's time and nearly all of its money, is less a method of controlling crime and enacting justice than a vast bribe factory for the officials within it. Corruption and cronyism run and shape the world of Annawadi, from the thugs who extort protection money from rag pickers like Sunil to the nun who takes expired food donated to her orphanage and resells it to street merchants. In one of the book's most eloquent ironies, Manju has to give up teaching the makeshift English classes she's been offering to the local children because she's too busy helping her mother administer an entirely fictional network of kindergartens funded by a Western nonprofit.

Boo mostly refrains from generalizing commentary; that's part of what allows "Behind the Beautiful Forevers" to hug its subjects as closely as their monsoon-drenched hand-me-downs. But when she does choose to pull back a bit, it's to comment on how magical thinking and conspiracy theory flourish in a world this arbitrary and unjust, a place that so glaringly lacks "a link between effort and result." A string of deaths in Annawadi are attributed to a curse prosecuted by Fatima's ghost, and above all, "powerless individuals blamed other powerless individuals for what they lacked ... Poor people didn't unite; they competed ferociously with one another for spoils."

You can see why some of the people Boo writes about give up, but what's more striking are the ones who don't. Abdul in particular makes for an arresting figure, a man struggling to work out the pattern of a virtuous life in an immoral world. Little Sunil cases the city outside Annawadi with an eye to unexploited opportunities. Manju joins a civil defense network so she can study the manners of its middle-class members. By the time "Behind the Beautiful Forevers" winds to a close, it seems almost unbearable not to know whether any of them will succeed. We can't. What happens next can't be told because it's still happening, right now.

Shares