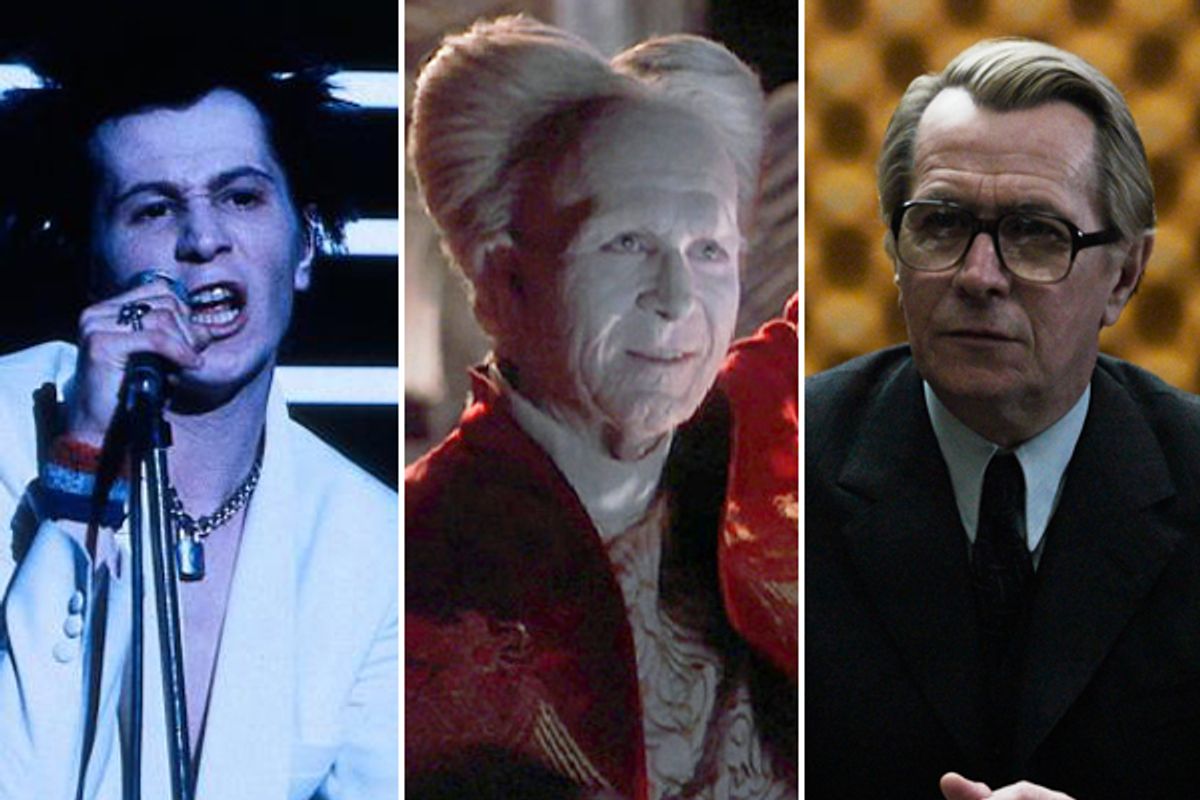

A woman in the audience gets up to ask Gary Oldman a question. He's finally been nominated for an Academy Award, 26 years after his breakthrough performance in "Sid and Nancy," she says, but it's for the quietest and most subdued role of his entire career. He has played Beethoven and Dracula and Lee Harvey Oswald, as well as Sid Vicious; does he regret that "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy" didn't allow him to show more emotional range?

Oldman is a reflective, soft-spoken fellow who considers questions carefully before answering them, but he doesn't have to think about this one. "It was greatly liberating, powerfully liberating, to play George Smiley," he says. If he plays a character who's called upon to cry, Oldman explains, "Those are Gary's tears. They have to be real. I've had to feel that grief or that anger, and then the performance is contaminated by that emotion." With Smiley, he goes on, he didn't have to display that emotion on the outside; the character is a profoundly melancholy, even tragic figure, but all that emotion is bottled up inside, in the classic English style.

Oldman recently made a brief visit to New York, to talk about the first Oscar nomination of a circuitous acting career that has taken him from the British indie fringe of the mid-'80s to major Hollywood roles and video games. (He is most famous among the schoolmates of his teenage sons, he says, for supplying the voice of Sgt. Reznov in the "Call of Duty" series.) I got to spend some time with him in two different settings: First as the moderator of a question-and-answer session at Manhattan's Sunshine Cinema, following a screening of "Tinker Tailor," and then the next morning over coffee at Oldman's Upper East Side hotel.

A performer of tremendous, almost chameleonic flexibility, and something of a cult figure for many younger actors and film fans, Oldman has never been in exactly the right spot for an Oscar to land on top of him. As the star of "Sid and Nancy" and "Prick Up Your Ears," he was too edgy and too English. As a memorable character actor in Hollywood movies like "JFK" and "True Romance," he perhaps seemed too damaged and disturbing. (Oldman explains that he settled on a key detail of the "True Romance" character after interviewing a Brooklyn teenager, who told him to replace the word "titties" with "breasteses.") His '90s roles as a leading man ("Immortal Beloved," "The Scarlet Letter," "Lost in Space") never clicked in quite the right way, although we should make an exception for Francis Ford Coppola's flawed but gorgeous 1992 "Dracula."

Now, at age 53, Oldman finds himself -- as he ruefully puts it -- almost an "elder statesman" of the film business. On "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy," he says, he got to work with both John Hurt, an actor he has long idolized, and Tom Hardy, a younger actor who idolizes him. "I might like to think of Tom as a peer and a contemporary, but I've got almost 20 years on him," Oldman says. "He'll say to me, 'Gary, I watched all your films when I was a kid.'"

As Oldman told the Sunshine audience, getting to play John le Carré's legendary spymaster was an amazing opportunity, but one he approached with trepidation and nearly refused. He was "absolutely petrified" about taking a role so strongly identified with Alec Guinness, who played Smiley in the legendary BBC miniseries of the early '80s. "You've got a knight of the realm, one of the most famous and most beloved British actors in our history. And if you asked almost anyone in the U.K., or at least anyone over a certain age, 'Who is George Smiley?' they'd say, 'Oh, right, that's Alec Guinness.'"

But just as director Tomas Alfredson's chilly, modernist take on le Carré's novel feels entirely different from the boxy claustrophobia of the TV series, Oldman's Smiley is quite a different creation from Guinness'. "No doubt there are parts of the character where I wind up in the same place as Alec Guinness," Oldman says, "but I'd like to think there are things in Smiley he didn't find. Ultimately, I think his Smiley might be a bit more huggable. I think there's a coldness, even a sadism to the character as I play him."

Across these two conversations, I found Oldman to be an exceptionally thoughtful and gentlemanly person, much closer in manner to the quiet but deadly Smiley than to the unstable, violent or passionate characters he was known for in his youth. Oldman's working-class London accent has been softened by nearly two decades in Los Angeles; he actually worked with an accent coach to make sure his performance as Smiley carried the correct upper-class Oxonian overtones. ("I was casting about a little bit to find his voice. And then I got to meet John le Carré, and said, 'Thank you very much. I'll take that.'")

If anything, Oldman comes across as an intensely private person who isn't terribly comfortable with the glare of celebrity, which may partly account for the fact that his leading-man career never quite took off and he's never previously been nominated by the Academy. He talks about film, theater and literature with obvious passion and knowledge, and never seems to give rehearsed answers. For instance, he says he's enjoyed playing Sirius Black in the "Harry Potter" series and Commissioner Gordon in the "Dark Knight" films, but also makes clear that those roles have been personally and financially beneficial. In the 2000s, he found himself raising two sons after a divorce, and didn't want to be an absentee dad. "I didn't want to be away from home all the time, and then I also didn't want to be the kind of father who dragged them all over the world. Doing those kinds of roles in those kinds of movies, you're making the most amount of money for the least amount of time."

Oldman is a genuine movie lover, a connoisseur of cinematography, costuming and music -- which makes him a particularly gratifying interview subject. While we were standing backstage waiting for the closing credits of "Tinker Tailor" to wind up, he talked about the piano theme, spreading his fingers on an imaginary keyboard: "Listen to that, so lovely. Then it goes all Russian!" When I meet him for coffee the next morning, we begin talking about the American movies of the 1970s that he likes best, starting with Roman Polanski's "Chinatown."

You were talking last night about your relationship with Los Angeles, and it struck me that you don't view the city as an outsider or a visitor, at least not anymore. It sounds like you love the place, and have complicated feelings toward it.

It's a shame about California, and particularly about L.A., where they've demolished so many landmarks. It's a bit of a disease there, where if anything is over 30 years old, they sort of knock it down and replace it. It's a strange town, it's this sprawling suburb, and then there's a city, the old town. It's as if someone wanted to build a New York or a Chicago, they got only so far and they gave up. They just abandoned it. I've lived there for 17 years, and I've grown rather fond of the place.

I'm guessing you must like "Chinatown," both because it's your kind of movie and also because it captures so much of that urge to destroy and rebuild.

Oh, yeah, "Chinatown." Sometimes it takes an outsider. If you look at Schlesinger's "Midnight Cowboy," it's such a microcosm of New York life at that time. He captured something about New York that was extraordinary. Polanski did much the same. Or a native can do it, a real native -- Scorsese or Woody Allen with New York, P.T. Anderson with L.A. and the Valley.

Here's another thing: These films, like "Chinatown" -- these movies were mainstream! You try to say to a younger generation, who are watching these movies on DVD, and getting their sense of history through that: "The Conversation," "Dog Day Afternoon," "Network," "Chinatown," "All the President's Men," "Marathon Man," "Taxi Driver." They were the movies you went to see at the cinema! They weren't particularly art-house movies. They played everywhere.

Sure. I went to see "Taxi Driver" with my dad at the mall, in suburban California. It's a little bit hard to imagine that particular movie playing there now.

Yeah, that's right. It's "Puss in Boots."

I feel like the early part of your career, from the late '80s to the early '90s, almost belongs to that era of movie history. I can't imagine Coppola's "Dracula" being made now, or not the way you did it.

Well, I certainly think that -- "Dracula," for instance, it's such a romantic movie. If you made it now, it would be a whole different animal. First of all, you're competing against the market that has movies like "Paranormal Activity." You'd have to deal with the scare factor. It was such a romantic take on the genre, and the book. This sort of tragic love story. I don't know if people would want that now.

They could turn it into a "Twilight" movie. You guys were a couple of decades ahead of the curve on that one!

Right. I mean the people that write checks might not want it. I'm not talking about an audience. And then there was that slump in my career. People say to me, "Oh, there was a while where you disappeared." There were many factors. I took a bit of a back seat, I had kids and I wanted to focus on them. There's that period in the late '90s, the early 2000s, where I didn't do a great deal. People say, "Oh, you had a slump in your career." And I say, "Really? Name me a movie. Name me a great movie from those years that I'd have wanted to be in." That was a real strange seismic shift in the industry. That was when it all really started to change.

A great deal of it was being exported, suddenly, and the kind of movies that they were making was very different. I was lucky -- I caught the very tail end of the indie thing, coming out of the late '70s and going into the '80s. With "Sid and Nancy" and "Prick Up Your Ears," those were the last of that. Then there was the Merchant-Ivory phenomenon, that happened for a while. And then Tarantino, with that voice, that great marriage of action and dialogue, the like of which we'd never seen before.

But if you go back to those '70s movies, you can't imagine those being made today. I watched "Network" recently, funnily enough -- I was on an Air New Zealand flight. Do you know there's not a note of music in that film? Not a note. And it holds up. It just works. Those stunning performances from people, especially Robert Duvall, who is marvelous in it. You think of Finch, of course, and Faye Dunaway. But for me it was Robert Duvall and, of course, Ned Beatty. You remember him? When he gets him into the office, and they do that scene down that long table, gives him that speech?

I'm sure we could talk about '70s films for a couple of hours, but why don't you tell me about the moment when you found out you'd been nominated for the Oscar.

I was in Berlin, rather fittingly. I was in the middle of what I thought would be my last interview for "Tinker Tailor." We were opening the movie there, and it was around 2:30 in the afternoon. My manager was watching the announcements in the hotel bar, and he came in looking flustered and a little teary-eyed, and said, "You're an Academy Award nominee."

We were already having anticipatory disappointment and anger. "Let's just get angry early" -- you know what I mean? Before we heard, I asked him, "Are you all right?" And he said, oh, he was just getting pissed off in advance. Tomas Alfredson, the director, went out for a walk. He couldn't take it. So he was out walking around at the Brandenburg Gate. If one had taken the temperature for the last month, with the SAG Awards and the Globes, we weren't part of it. So I wasn't expecting anything. It was quite a shock.

I think I said this last night: You can let it overwhelm you and stress you out, give you anxiety. You can be cynical about it, or you can be, I think, overly modest -- "I am not worthy," that kind of thing. Or you can enjoy it. And I'm just having a great, great time, riding in the front cabin. It's nice up there!

People in my position spend a lot of time fretting about whether the Oscars still mean anything to the culture at large, whether they mean what they used to, and so on. I wonder how that question looks to you. Do you feel like you've finally been accepted as a son and brother in Hollywood, after all these years?

I mean, I've never felt excluded, exactly. I am a participating member of the Academy and all that. But I think the answer is yes. You become an elder statesman, don't you? A veteran. I've put the years in, I've got quite a body of work. And it's particularly nice for me that it happened with this film and this character. I know some people who've been in this situation who have not had a good time. They get nominated, and they didn't have a particularly good time on the movie, or they might not like the director. That's got to be bittersweet, because you're excited for yourself that you've been acknowledged, and yet you have a taste in your mouth from the experience.

This was a Rolls-Royce from the beginning, with Tim Bevan and Working Title, Robyn Slovo, the producer, Tomas Alfredson, the director -- and this cast of actors! You know? So I'm very happy that it happened with this one. And we'll see, who knows. It's an achievement to make the top five.

And then, what you mentioned about the Oscar -- where it is culturally, does it still mean the same thing, all of that. It certainly feels like it does from the inside, that's for sure. It's a big deal from where I'm sitting. What it means to the public -- it's a question I've never really asked anyone, you know? It's never really come up. As an insider, you can take it or leave it, you can be cynical, you can dismiss it. It's easy to be on the outside and criticize it. To me, the Golden Globes -- that one is a puzzlement. There's not one journalist I've spoken to who hasn't had a comment or made a remark. Or rolled their eyes, as you are doing now. [Laughter.]

As you say, you've got quite a body of work, but this role feels quite distinct. Smiley is so quiet and calm, and you have a reputation for playing exaggerated, emotional characters. So much of the film is you being impassive, or at least seemingly impassive, underreacting rather than overreacting.

I'm excited and happy about the nomination precisely because of that. It's not so showy, so extroverted. There's a lot going on, but it's like a simmer, isn't it? It's a small flame. It's ironic, I suppose. There have been a few in the repertoire that have been more bombastic and showy, but I have to say this feels right. I don't know -- does that make sense? It's a more mature piece of work.

I agree. I get such a powerful sense of depression or melancholy from Smiley. From the whole movie, actually, but especially from this tremendously still and quiet performance you give at the center of the movie. It's like all the anxiety and sadness of post-war England compressed into one guy.

Well, he's a romantic. A disenchanted romantic, one of the last. And he's having to deal with these people, these new people in this new war, where it's God versus Marx. There are suddenly all these questions, all these philosophies to deal with. I thought when I was working on it, "What would a psychiatrist, a therapist, say to Smiley in this day and age?" Look at that relationship [with his constantly unfaithful wife], it's very dysfunctional, it's very inappropriate. Someone might say to him, "Why don't you feel that you deserve more than Ann? Why are you happy with scraps from the table, and not a full meal?" Those are the questions I asked myself; that's what I was playing. That sadness that he carries around. I think, also, that he knows that the mole is Bill Hadon [played by Colin Firth] before I let you know it's Hadon. So there's this double betrayal.

When he talks about meeting Karla [the legendary KGB spymaster], and I have that monologue ...

Yeah, about meeting Karla and figuring out his weakness. Which is such a great scene.

Smiley feels a little bit responsible for creating Karla, because he was the one person Smiley couldn't crack, and he got away. And subsequently Karla became Karla -- you see, I'm not being cuckolded by Bill Hadon, I'm being cuckolded by a man who's thousands of miles away, this is how clever he is. But Smiley invites Peter Gwillam [Benedict Cumberbatch] up and they have whiskey, and then Smiley says to him, indirectly, don't have a relationship. You want to be successful in this business? Don't be involved. It's his way of saying, I let him go, you see? Maybe you should tidy up your own affairs. [Long pause.] It's fucking brutal, it gets me every time. The casualties of it.

I also found it chilling when Smiley says he has found Karla's weakness, and that's the fact that he's a zealot, a true believer. Which raises the question of what Smiley believes in, or if he believes in anything. It's the great mystery of the character.

Well, he's become cynical, and the cynicism is there in the writing. I think it's there in great writing. I think Arthur Miller has it, Tennessee Williams has it. I don't even think great writers are even conscious of it, but there is that thing: Are we any better than you, when we think about it? Aren't we really the same? What's it all about?

Now we're lucky. We look back at that period and we wonder: Should we have been as paranoid as we were? Perhaps not. What was all that about? But at the time, you know, it all felt very different. It's an extraordinary piece of writing, a terrific creation. I'm very fortunate to have gotten to play it.

Shares