On Tuesday, David Foster Wallace would have turned 50 years old, an occasion that has even inspired conferences. After his death and canonization into what looks like an entire field of academic study, there remains a popular critical notion that Wallace is to be solely known as a writer of fiction. These are typically readers who swear by "Infinite Jest," a work that is indeed Wallace’s crowning achievement, but by no means his only. They acknowledge his other fiction, but refuse to credit him as having also been a skilled nonfiction reporter. Or, they happily acknowledge that there are many readers that go right to Wallace's essays and skip the fiction altogether, but simply consider this a mistake.

There even seems to be a now common agreement in academia that readers who champion Wallace’s essays as their favorite work of his are simply missing something and must be less advanced readers, because his nonfiction couldn’t possibly hold up to his one towering opus. It’s a facile assumption that accessibility signals lack of seriousness.

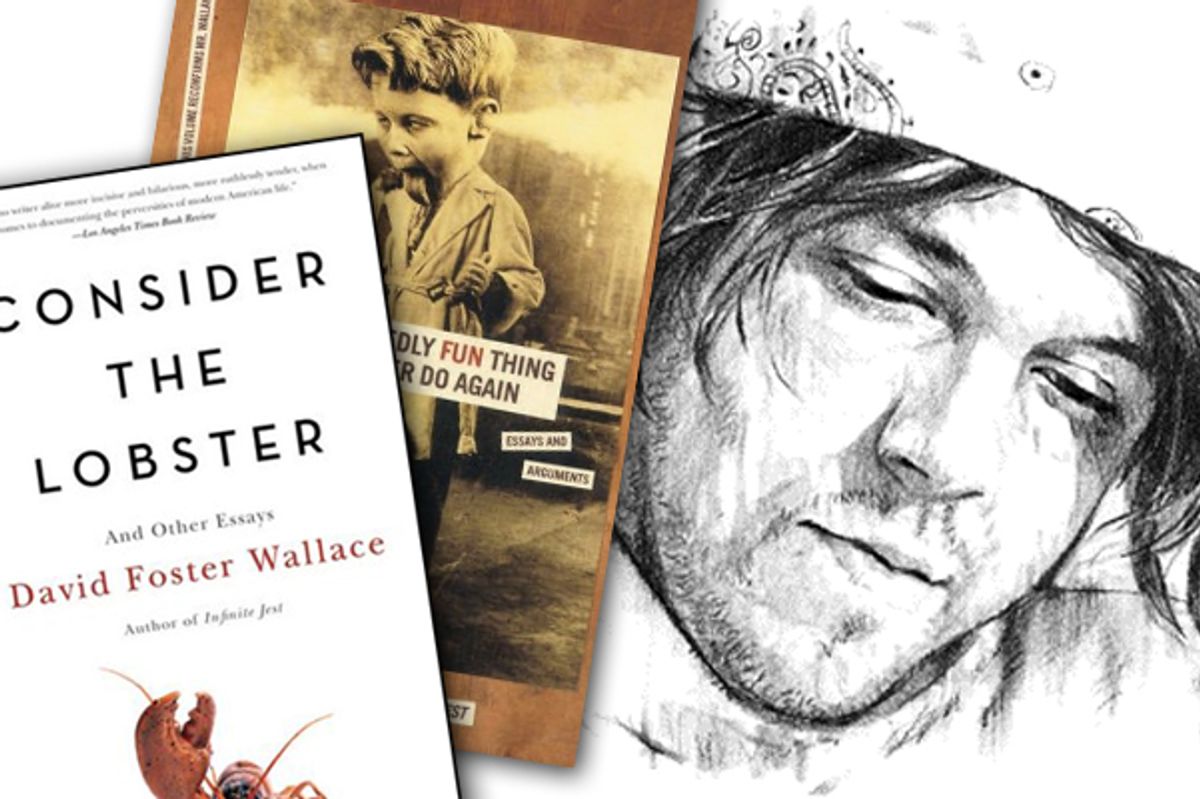

It doesn’t help matters that Wallace himself said, on occasion, that he is no journalist. “I think of myself as a fiction writer,” he told Charlie Rose in 1997, just after the publication of "A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again," a terrific collection of essays. “And I’m not even a particularly experienced fiction writer,” he added, in trademark self-deprecation.

A year ago, on Slate, Tom Scocca stoked the “not a journalist” theme further (those words even composed the article’s headline). Scocca posted the transcript of an interview he did with Wallace in 1998, in which Wallace said, “The weird thing about the nonfiction is, I don't really think, I mean, I'm not a journalist, and I don't pretend to be one … The thing that was fun about a lot of the nonfiction is … it was just mostly like, yeah, I'll try this.”

It would be weak to take Wallace’s tongue-in-cheek humility as definitive evidence of what he was or wasn’t as a writer. Wallace was likely aware, even in his more self-doubting moments, that he was a skilled reporter (he certainly enjoyed it, at least). Yet even if he didn’t realize the rich tradition into which his style of nonfiction fit perfectly — even if, as he let on, he bought into the idea that he was merely pretending — it should not preclude the literary establishment from considering his talents in this second, less showy role to be equal to the studied brilliance of "Infinite Jest" and his other fiction. “I’ll try this” can certainly be the mantra of someone who nonetheless succeeds immensely in a new form, whether they’re fully aware of the success or not.

In his nonfiction, Wallace most closely resembled another writer before him, a man who was also considered something other than a journalist: Hunter S. Thompson. Both writers took reportage a step further than the literary techniques of Gay Talese, Joan Didion and the New Journalism. Yes, both Thompson and Wallace shirked objectivity, happily injecting their own commentary and asides into factual reportage, but today scores of journalists reject objectivity (Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi, Esquire’s Tom Junod or, to a lesser extent, Jon Krakauer, who certainly makes his own views clear by the end of "Where Men Win Glory").

What Thompson did differently that Wallace emulated (consciously or not) is more about a slippery definition of honesty and truth. An essay Wallace wrote about attending the Adult Video News (AVN) Awards opened the collection "Consider the Lobster." It’s a rollicking tour in which the author plays representative for the reader’s disgust and fascination (when a girl meets Wallace and brags about small valves in her new breast implants that allow her to adjust the size of the breasts by adding or draining fluid, she raises her arms to show him and Wallace can only write, “There really are what appear to be valves”).

But the essay, it seems, stretched the truth of what happened to Wallace at the AVN Awards. Evan Wright, author of "Generation Kill," was also at the 1998 event and spent some time guiding Wallace around. He appears in the essay as “Harold Hecuba” and as many people have noted, his own account of the events differs from Wallace’s. Notably, he tells Wallace a brief anecdote about meeting a cop who professed to be a porn fan. Wallace expanded the story into a much larger chunk and seems to have added to the quotes relayed to him by Wright, embellishing them a bit. Blogger Annlee Ellingson has a more detailed side-by-side comparison of the story as relayed by Wallace in “Consider the Lobster” and then by Wright in an L.A. Weekly piece, but aptly concludes that Wallace, “writing about somebody else’s anecdote, in a footnote, no less … gives a much more complete picture of the entire scenario” and uses it “to expound on the entire adult-entertainment industry.” Nevertheless, this may be the reason Wallace called his nonfiction stories “essays” and not “journalism,” but from a perception point of view, it almost shouldn’t matter.

The same goes for his massaging of the facts in other essays. In October, during a New Yorker Festival event, Jonathan Franzen stirred up some drama when he told David Remnick that "David and I disagreed on," as Remnick raised it, a "view of fact and fiction" and the "dividing line" between the two. Remnick, aghast, asked if Wallace "said it was OK to make up dialogue on a cruise ship" and Franzen confirmed that, indeed, he did. Pushing aside for a moment the question of why Franzen even felt the need to randomly interject about Wallace (and the jealous, complicated feelings Franzen has demonstrated publicly for his friend), the idea that Wallace's occasional use of invented dialogue makes him, by definition, not a journalist is a laughable one.

As Michelle Dean aptly noted in a piece for the Awl, "It's very hard to say whether Franzen's charge is (a) true ... or (b) new information." It certainly wasn't new information for most Wallace devotees, and as for whether it's true to contend that Wallace made up dialogue, the evidence says otherwise. This is a person who, as the Awl piece points out, felt extremely bad about his portrayal, in the cruise-ship piece "Shipping Out," of two of the people he met on the cruise. And yet even as he described his shame over insulting this couple who had befriended him, he reaffirmed the accuracy of the meaner parts of his portrayal, describing the wife as "a terrific, really nice, and not unattractive lady who did happen to look just like Jackie Gleason in drag."

If he did on occasion tweak direct quotes, it didn't affect the truth of the situations, and if anything likely got closer to a representation of truth, at least the personal, first-person narrator sort of truth that the cruise-ship piece and others like it aimed to convey. The cruise piece, among many others, delivers an extremely satisfying, complete representation of Wallace's own personal experience (a very bad one) on the cruise, and if altering dialogue served to better crystalize and define that experience, then it's still truthful, no matter what David Remnick or his fact-checkers would say. (For more on this ever-raging debate, read John D'Agata's new book "The Lifespan of a Fact," though D'Agata strays much further off the rails of allegiance to fact than Wallace ever did.)

As for Hunter S. Thompson, the man is certainly revered today — movies are made of his books, like "The Rum Diary"; documentaries present him to wider audiences — but his career is continually diminished by the term “gonzo journalism.” Those who use it, to this day, do so to point out his craziness, lies and unreliability. Yet “gonzo,” with its negative connotations, fails to reflect Thompson’s passion for truth and devotion to accuracy. What makes his writing so engaging is that no matter how far off the rails he allows himself to stray (he titled his eulogy of Richard Nixon “He Was a Crook”), he maintains investigative honesty. In most of his work, Thompson plays a sort of intimate, dunderheaded guide, walking the reader through whatever event he may be chronicling. The same goes for Wallace, a Virgil guiding us as he traverses hell, whether that's a porn convention or an old woman’s house as she watched 9/11 unfold on television. Wallace said as much to David Lipsky in "Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself: A Road Trip With David Foster Wallace": “In those essays … there’s a certain persona created, that’s a little stupider and schmuckier than I am.” This confession also stands as a sort of mantra for Wallace’s journalism.

In his article “Seething Static: Notes on Wallace and Journalism,” Christoph Ribbat of the University of Liverpool writes that “there is nothing particularly ‘bold’ about Wallace’s nonfiction, at least not the kind of boldness that Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson and Mailer developed to establish themselves as maverick heroes.” But that’s the point: Wallace didn’t want to establish himself as a maverick hero; instead, he echoed Thompson’s techniques in order to create something more accessible.

Some of the same tricks Wallace used in “Big Red Son,” Thompson enacted before him, particularly in "Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72" and in “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,” an assignment for the now-defunct sports rag Scanlan’s Monthly. Thompson was asked to write a story on the famed race, but instead wrote about the drunk, drugged-out crowd that attends it, Thompson and his illustrator Ralph Steadman included.

“Big Red Son” has one scene that, whether by coincidence (possible) or intentional tribute (more likely), directly mirrors a scene from "Campaign Trail." Wallace writes: “A strange and traumatic experience … consists of standing at a men’s room urinal between [porn stars] Alex Sanders and Dave Hardman … The urge to look over/down at their penises is powerful and the motives behind this urge so complex … Be informed that male porn stars create around themselves the exact same opaque affective privacy-bubble that all men at urinals everywhere create.” Yes, he’s going for shock factor, but he’s also telling you something, and above all else, he’s playing the wide-eyed Average Joe.

The similar moment in "Campaign Trail" happens when Thompson cleverly (if inappropriately) takes advantage of a vulnerable moment to speak to George McGovern, whose campaign he is covering: “By chance, I found George downstairs in the Men’s Room, hovering into a urinal and staring straight ahead at the grey marble tiles.” Thompson proceeds to interrogate McGovern on a touchy subject — McGovern’s reaction after his good friend Harold Hughes endorsed a different candidate — and carefully observes his body language at this moment of weakness: “He flinched and quickly zipped his pants up… I could see that he didn’t want to talk about it.” This is what Thompson and Wallace do; they take every potential opportunity, no matter how unusual or taboo, and mine it for information and storytelling value. And the same blend of intrigue, humor and discomfort that Thompson achieves with the urinal scene is present throughout “Big Red Son,” like when Wallace brazenly notes that a porn director forced a starlet to stick a pen “up her asshole.” He then, in his essay, doesn’t just include the actual phrase she scribbled down, but copies the phrase into his text in the same jagged handwriting with which she originally wrote it in the director’s notebook. The result: that messy, unsettling feeling in the reader, the same Thompson often embraced, a feeling that signals fearless journalism.

“Consider the Lobster,” the title essay of Wallace’s collection, is itself another piece of evidence linking Wallace to Thompson. When the food and travel magazine Gourmet assigned Wallace to write an article on the annual Maine Lobster Festival, he ended up musing about the ethical dilemma that cooking a lobster alive presents to eaters. Implementing facts and figures along with his own judgments, Wallace reaches no final conclusion but rather poses the question directly to Gourmet readers, asking them, “Do you think much about the (possible) moral status and (probable) suffering of the animals [that you eat]? If you do, what ethical convictions have you worked out that permit you not just to eat but to savor and enjoy flesh-based viands?” This essay in particular makes it a shock that he’s rarely remembered as a journalist; just look at what he was doing with the form. Thompson took a similar avenue with "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas": “Cover the story. Never lose sight of the primary responsibility. But what was the story? Nobody had bothered to say. So we would have to drum it up on our own.”

When the Atlantic’s Matthew Hahn asked in 1997 if he thought any younger writer was approaching nonfiction in the same style as he did, Thompson answered: “I don't think that my kind of journalism has ever been universally popular. It's lonely out here.” But Wallace, in myriad ways, was that heir. (He also burst onto the nonfiction scene right around the time of Thompson’s interview with Hahn.) Like Thompson, he killed himself (though at a far younger age) and dealt with depression. Of course, it’s the writing that counts, and the writing irrefutably reflects Thompson’s influence.

In 1997, Wallace told Charlie Rose, regarding his nonfiction essays: “If there’s a shtick, the shtick is, Oh gosh, look at me, not a journalist, who’s been sent to do all these journalistic things.” Whether or not Wallace fully believed in the shtick he created, the evidence — his outstanding reportage — speaks for itself.

Shares