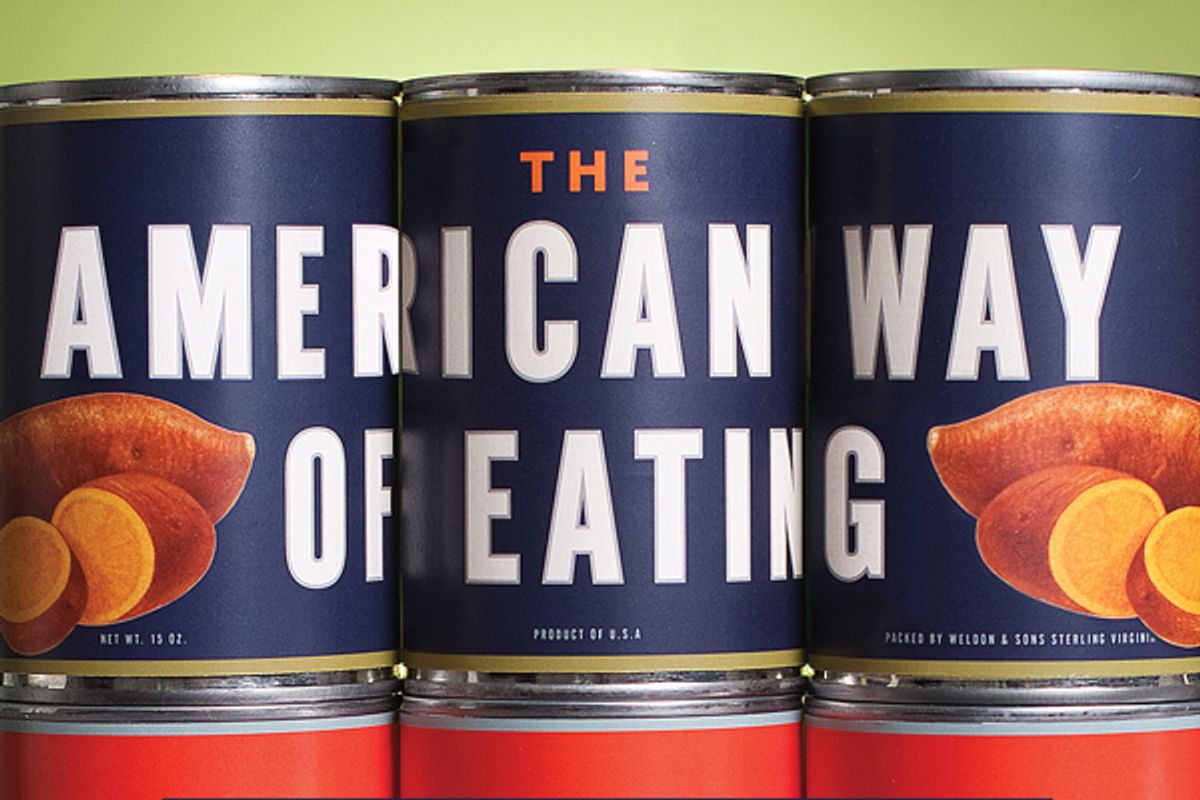

You may not be truly shocked by any single statistic in Tracie McMillan's new book, "The American Way of Eating: Undercover at Walmart, Applebee's, Farm Fields and the Dinner Table" -- but by the time you finish reading, you'll definitely feel the impact of her cumulative case.

McMillan spent months exploring the American food system from three different angles: picking produce in California fields, working in two Michigan Walmarts, and expediting (organizing the flow of food from the kitchen to the dining room) at a Brooklyn, N.Y., Applebee's. By turns analytical and anecdotal, her book marshals first-person experience, history and current research to paint a picture of America's 21st-century food reality.

McMillan asks why the distribution of good, healthy food -- easy access to which she considers a human right -- is so often left to private companies, begging us to change the conversation from one about what people eat (she thinks that given the choice, people will eat relatively healthily) to one about healthy food's accessibility.

Over the phone, McMillan explained her project's goals, and shared insights from her experiences as an embedded food journalist.

One of the arguments you make throughout the book is that food is a "social good" and a human right. You sometimes even cite the Founding Fathers and their desires in the course of your argument. What's the basis for that? Do you think everyone would agree that healthy food is a right the Founding Fathers thought all Americans deserved?

That's more of a rhetorical flourish, I think, than anything that's enshrined in the Constitution or any founding documents. But it refers to a very different time in America's history. The Founding Fathers weren't living at a time when you could possibly have thought that food would be this weird stuff that came in boxes and you pulled off shelves, the way you do now. That model didn't exist -- supermarkets didn't exist until 1930. So I think the idea that getting fresh, fairly healthy food would be difficult or unusual anywhere would not have occurred to them.

Obviously, diet has always correlated somewhat with social class. I have a quote in the book somewhere, from Jefferson, about how there's less fresh food in the diet of the poor than that of the rich. He says that this is bad (but he says it in a much more beautiful and thoughtful way than that). I think when you have Founding Fathers talking about [that state of affairs] being unconscionable, and not being what they're going for when they're building the founding premises for the nation, and when you look at how our food system has changed over time, it's reasonable to say that none of them would be particularly happy with the fact that, in a country that's as rich as the U.S., fresh and healthy food is seen as a luxury, as opposed to something that everybody has a right to and has access to.

To the extent that any of us accept government, we accept that government has a responsibility to ensure really basic parts of human existence to its citizens. Water, roads, electricity -- we spend time and energy and money on the part of public entities to make sure that everybody has access to these things. And yet we've left food entirely to the private market. We have lots of food in lots of places, but there's very little fresh and healthy food in some places, and that's mostly because supermarkets have one set of incentives to succeed, and they don't always line up with making sure we all have really healthy food. When we expand cities, we put in water lines and electricity lines -- and the government will make sure that that happens and it's not too expensive -- but when it comes to food, we say, "Oh, whatever, we'll just see what shows up." And often what shows up is not great.

You make another, similar point in the book: that we make sure kids know how to read, but we don't make sure they know how to cook.

Well, obviously, I think literacy is really, really important in terms of books ...

But it doesn't help you survive on the most basic level.

Right. Traditionally, we've thought the point of a school is to create a workforce. So we teach people all these workforce skills. That model evolved at a time when it was pretty common, at least for middle-class families, for women to stay home. Women would spend time and energy in the kitchen, cooking -- and could then teach kids how to cook. Now, that's not the norm. There are all these competing social and work pressures that make it really hard for folks to cook at home and to spend a lot of time on it; also, as there's more and more academic pressure on kids to do all this stuff after school, there's just less time for that kind of learning. If you're going to start building a society where that stuff can't very easily be taken care of at home, you need to start looking for [alternatives].

To me, cooking seems like one of those really basic skills that everybody should have; that's part of literacy in terms of a broader sense of human existence. If we want people to eat healthfully and be engaged with their diets, the easiest way to do that is [by teaching them to cook], right? And then people can really be empowered to make decisions for themselves.

If you're talking about a socioeconomic situation where people don't have a lot of time to cook, and don't necessarily have a lot of cooking knowledge, and you're telling them they should be spending more time cooking, that's not really fair. But if you're creating a social fabric where there is lots of time and energy, that's different. I draw some comparisons with the way industrialized nations in Europe structure their work and social time and vacation time. If I had five weeks' guaranteed vacation every year, I'd be a lot more into canning the stuff out of my garden.

In each of the three places you lived and worked for the book, how representative would you say your experiences were?

It's important for me to be very clear that, obviously, in a major sense, these experiences are only representative of what happens when I go and do what I did. Because, particularly in the farm work, I'm a white girl with papers -- there's no way the experience I had is entirely typical. I also write about this in the Applebee's section: People were really excited and curious about having a white girl in the kitchen. There's all this interesting stuff about being a white woman. It prompts exploitation, on some levels, but also a lot of protection and affection and curiosity ... I do think that in communities where monetary resources are tight, people do a lot more for each other in terms of in-kind resources.

One point you make several times seems key to the discussion of healthy eating choices: When you're working very hard, and you're working a job that's tiring, there's an apathy that takes over and ultimately dictates the food you choose to eat. I think people in almost all circumstances will recognize that exhaustion and overwork leads them to be less careful with their diet. Is there an easy way of combating this?

I think you're right that you'll find this with everybody. Most people have been exhausted from working, no matter how rich they are. [When they hit that point,] they just think, "I don't care what I eat."

I do think that there's a special quality to these very working-class jobs, though. I experienced this the most at Walmart, where you feel like you have so little control over anything in your life that it just seems ridiculous to say, "I'm going to be really positive and work really hard on my diet."

This sounds a little touchy-feely, but one of the things that you need to have to eat well is a real drive to do it: a real sense that what you do matters, and your circumstances will change. When you're working in these jobs where actually, you can work really, really, really hard, and your circumstances do not change, that sense of "I will work hard and nothing gets any better" pervades everything. You feel a kind of hopelessness setting in about everything in your life.

This is part of a larger argument that you're making -- that we can't just change our attitude to food directly; we have to address all these other concerns before we get to the point where people choose what they're going to eat.

Right. The deeper I got into doing this project, the more I began to believe that we shouldn't just focus on talking about what we should be eating. My grandmother has been telling me since I was a kid, "Eat your vegetables." I've found a lot of sustainable food stuff really inspiring and really exciting, but I really think that people already know about it. What we need to think about is, Why aren't people doing it?

We've developed this approach to nutrition in the U.S. where we think that if you just tell people things in the right way, they'll change their minds -- that we need to persuade people to eat well. I don't think that that's the case. I think that you get a lot further by making it easy for people to make good decisions ... If you make it easy for people to eat well, people mostly are going to do that. People are not running around saying, "I think diabetes is awesome and I want it." Right now, it's really easy to eat crappy food. So, why not make it easier not to?

Lastly, what would you say are the most surprising things -- either alarming or encouraging -- that you learned over the course of your experience?

There were two things that freaked me out the most. One was how totally unregulated farm labor is on the ground. I remember thinking, "Nobody is minding the shop here. Absolutely nobody." I was getting paid completely illegal wages, and they were giving me paychecks that I could completely disprove if I felt like arguing about them. But even if anyone bothers to complain, the fines are really small -- no one really cares.

The other alarming thing was the sense I got of the power of Walmart -- how powerful a single company is in terms of our food system. They're not just the ones selling the food; they're the gatekeepers between farm and plate. They're controlling the whole thing. It's how they've brought prices down: not so much by pushing down producers' prices, which they've done on manufactured goods a lot ... more of the food price drop over time has been a drop in the price after the farm gate. We talk about the fact that banks are "too big to fail" -- and that's awful. But it scares me even more when we're talking about food.

On the other hand, there were a bunch of things that I found really inspiring. I thought the generosity among the people that I worked and lived with everywhere was really amazing. There seems to be this myth -- and this might be part of the way that I grew up -- that everybody's out there on their own: We're individuals, and we just take care of our own stuff. But actually, people -- particularly of limited means -- are incredibly generous and kind, for the most part.

I came out of all of this feeling really hopeful. We can actually do this. This isn't some huge monolith that's impossible -- we just have to decide that we want to take on the less sexy things. Let's talk about food as part of infrastructure. If we could get people as excited about food infrastructure as they are about farmers' markets, we'd get really far really fast.

Shares