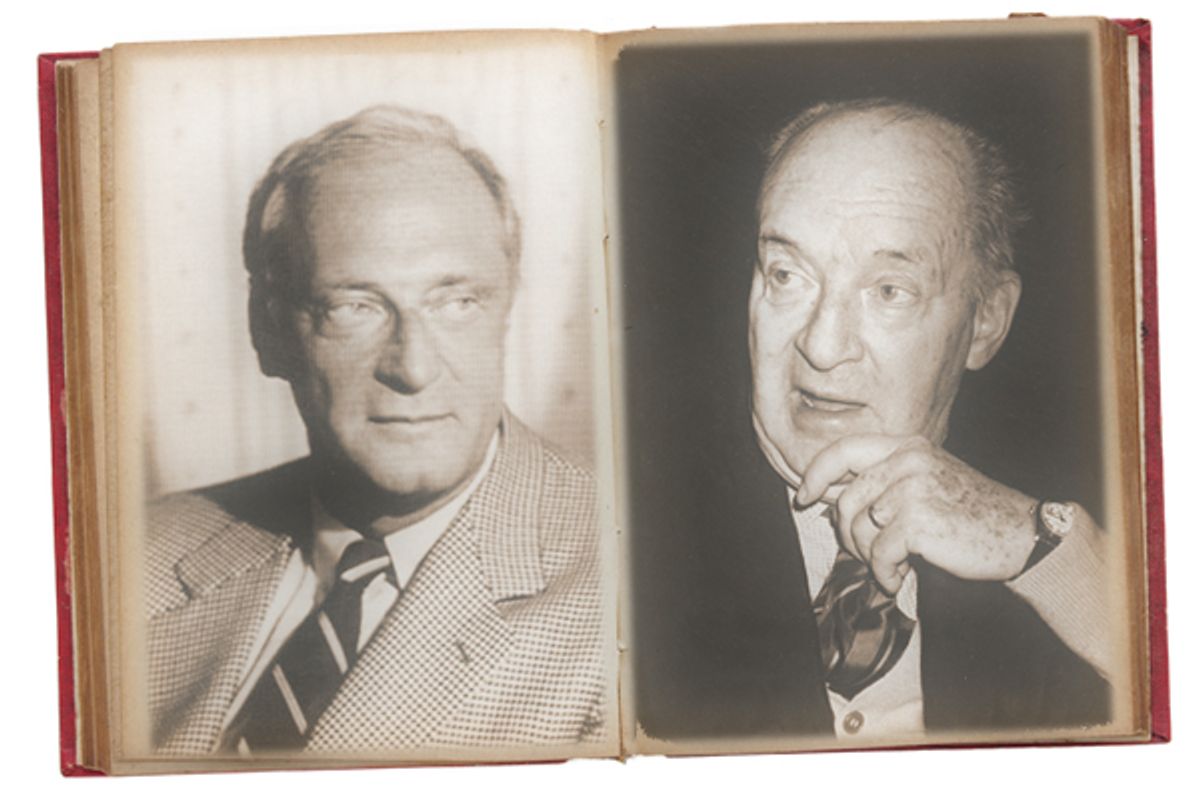

According to his obituaries, Dmitri Nabokov, who died in Switzerland last week, was a race-car driver, a basso profundo opera singer and a bon vivant. Above all, though, he was a literary executor, one of the most formidable of our time. That's saying a lot. We live in an age of some very daunting keepers of the flame.

Dmitri, who translated and edited his father Vladimir's work, was renowned for slapping down critics or biographers who dared to "misinterpret" that work or the man who produced it. Relatives who serve as the agents or the executors of a late author's estate usually control the rights to reprint excerpts from the author's published works and access to unpublished material. Appeasing them often becomes the most ticklish challenge facing anyone who wants to write about -- or even merely celebrate -- the author or the books.

Some executors are more aggressive than others; in 1998, Dmitri Nabokov's threats of legal action for copyright infringement against the English translation of an Italian novel, "Lo's Diary" by Pia Pera, caused the book's American publisher to withdraw it. The novel was later brought out by a small press headed by Barney Rossett -- a legendary maverick publisher who also died recently -- according to an agreement with Dmitri Nabokov. He compelled them to include a preface to Pera's novel in which he disparaged it as a "derivative" work by a "would-be plagiarist." (The novel retells the story of "Lolita" from the title character's perspective.) To make it clear that his objections were based on principle rather than profit, Dmitri Nabokov demanded a cut of the proceeds from "Lo's Diary" and then donated it to the global writers' association, International PEN.

Perhaps the most notorious literary executor alive is Stephen Joyce. Grandson of James, Stephen's reign over the writings of the great modernist has been "ferociously prohibitive," according to the British newspaper the Independent. For example, he filed suit against the Irish government over a 2004 festival that had scheduled live readings of excerpts from "Ulysses" on Bloomsday (the date, June 16, during which the novel takes place). This hypervigilance was reputedly fueled by his indignation at seeing sexually explicit letters written by James Joyce to his wife, Nora, published by Joyce biographer Richard Ellman in 1975. In 1995, Stephen Joyce announced that he would cease granting permission to quote from his grandfather's work entirely.

Stephen Joyce's iron grip was forcibly loosened earlier this year, when his grandfather's published works entered the public domain in the European Union. (Different rules apply to published and unpublished works, and the duration of copyright varies from nation to nation.) Perhaps foreseeing such an eventuality, Stephen Joyce announced in 1988 that he had destroyed a cache of letters he'd received from his aunt Lucia, James Joyce's schizophrenic daughter, explaining to the New York Times that "there is a part of every man or woman's life, no matter how famous he or she may be, that should remain private." However, in 2007, an American professor, Carol Loeb Shloss, won the legal right to publish material the Joyce estate had forced her to remove from her book "Lucia Joyce: To Dance in the Wake." Two years later, the estate agreed to reimburse her for a quarter of a million dollars in legal fees.

These are by no means the only cases in which scholars and biographers have locked horns with literary heirs. George Orwell's widow tried unsuccessfully to withdraw her waiver of copyright when she discovered that the biography she'd authorized (by Bernard Crick) did not tell the story as she saw it. T.S. Eliot's widow (still alive!) has bestowed and withdrawn permission to various parties for similar reasons and delayed the publication of a volume of his letters for decades.

But perhaps the most bizarre case of zealous literary executorship surrounds the work of Sylvia Plath. As with Joyce, the poet's writing is significantly autobiographical, but Plath's personal story has become particularly entangled with her literary legacy. When she committed suicide in 1963, she was separated from her husband of six years, Ted Hughes, who had left her and her two children for another woman. As the mystique surrounding her death grew, many observers came to regard Hughes as the villain in a drama epitomizing 20th-century marriage and its discontents. Others simply noted that Plath's widower had an interest in how the story of their relationship and her suicide would be told.

Hughes inherited Plath's literary estate. When he oversaw the publication of her journals in 1982, he caused an uproar by explaining, in the book's foreword, that he had destroyed one of the journals and lost another. These two volumes just happened to cover the period leading up to her death, when their marriage had fallen apart and Plath was writing the poems that would make her reputation. Hughes' stated reason for destroying one of the notebooks -- "because I did not want her children to have to read it" -- failed to persuade many of his critics.

The situation was further complicated when Hughes appointed his sister, Olwyn, to act as the literary agent for Plath's estate. Olwyn disliked Plath and was enraged by any attempt to portray her brother as culpable in the tragedy of his wife's death. While most literary executors want to make their author seem a better -- or at least a more decorous -- person than he or she actually was, Plath was in the odd position of having the raw material of her posthumous reputation fall into the hands of a woman who preferred to make her look bad. This, naturally, clashed with the rising tide of Platholatry, and Olwyn Hughes harried a series of Plath biographers, most of whom eventually threw up their hands and went the unauthorized route. The one biographer who submitted to the dictates of both Hughes siblings, Anne Stevenson, was widely condemned for whitewashing Ted.

The awkward, even perverse dynamic between literary heirs and the scholars seeking access to their riches has inspired one great novella: Henry James' "The Aspern Papers," in which a researcher pretends romantic interest in the niece of an old woman who may possess some highly desirable letters. The Plath estate, in turn, provided the occasion for a great work of nonfiction: Janet Malcolm's "The Silent Woman," an investigation of the poet's feuding biographers and family members. Like all of Malcolm's work, this is a book full of scouring observations about self-delusion and human nature: "The organs of publicity that have proliferated in our time are only an extension and a magnification of society's fundamental and incorrigible nosiness;" "Relatives are the biographer's natural enemies; they are like the hostile tribes an explorer encounters and must ruthlessly subdue to claim his territory"; "The pleasure of hearing ill of the dead is not a negligible one, but it pales before the pleasure of hearing ill of the living."

Malcolm is so constitutionally incapable of idealizing anyone that she comes to seem the only reliable guide through the crazed hall of mirrors that is the Plath industry and its equally fiery opponents. As miserable as some of these people are made by their squabbling, you can't help being glad that it produced such a book.

We can also honor some executors for less indirect gifts to literature. Dmitri Nabokov dithered for years before finally publishing an unfinished novel, "The Original of Laura," that his father had instructed him to burn. The manuscript turned out to be relatively uninteresting to anyone besides Nabokov buffs, and it provoked a lot of agonizing about an executor's responsibility to the dead.

To justify his decision, Dmitri Nabokov pointed to his father's approval of the greatest act of executor disobedience ever: Max Brod's refusal to destroy the life work of his friend, Franz Kafka, after Kafka's death in 1924. The world would be a much poorer place had he not defied Kafka's will and published the work. There remain, in fact, some Kafka papers that have not yet been published, although what, exactly, they are remains a mystery. Brod's heirs have them, and they're not sharing.

Further reading

New York Times obituary for Dmitri Nabokov

Martin Garbus for the New York Times on the legal dispute over Pia Pera's "Lo's Diary"

Dmitri Nabokov's preface to "Lo's Diary"

D.T. Max for the New Yorker on Stephen James Joyce and his grandfather's estate

The Independent on the passing of James Joyce's works into the public domain

Salon's Kate Moses on the controversy over Sylvia Plath's journals

Elif Batuman for the New York Times Magazine on the battle over Franz Kafka's papers

Shares