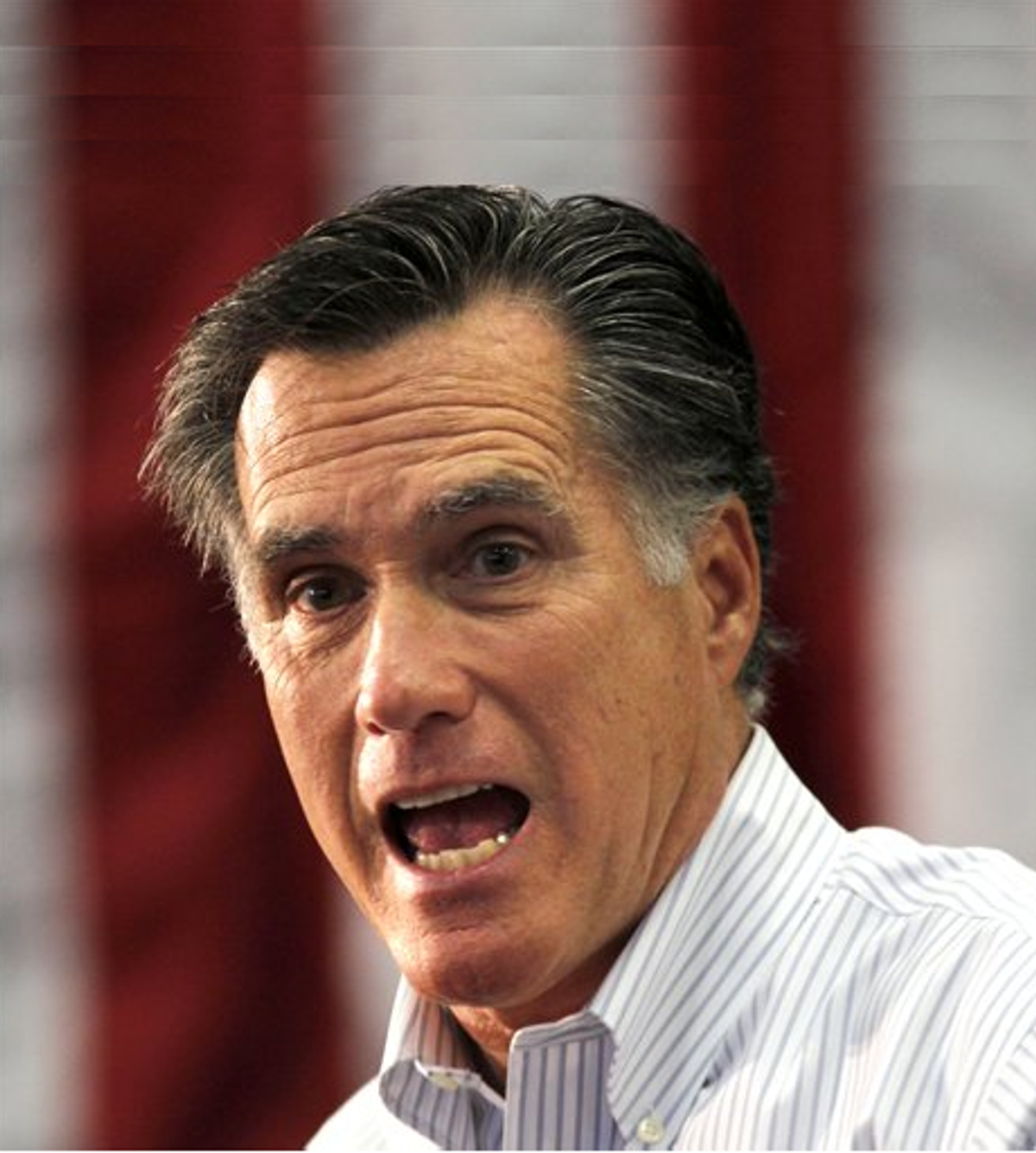

According to his own version of events, Mitt Romney “simply misunderstood” an Ohio television reporter who asked him Wednesday afternoon about the Blunt amendment, the vehicle by which Senate Republicans hope to override the Obama administration’s new rules on contraception coverage.

Romney caused a stir when he replied that “I’m not for the bill,” a position that would put him at odds with literally every social conservative activist in America on what has become a defining issue for the right. It would also represent a jarring shift by Romney, who has loudly joined the chorus of Republicans decrying Obama’s supposed “attack on religious conscience, attack on religious freedom.”

So when the reporter who asked him the question, Jim Heath of the Ohio News Network, incredulously tweeted out Romney’s reply, the political world took immediate notice and a brief frenzy ensued – at which point Romney said that “the way the question asked was confusing” and pronounced his full, enthusiastic support for the amendment.

“Of course I support the Blunt amendment,” Romney insisted. “I thought he was talking about some state law that prevented people from getting contraception. So I was simply – misunderstood the question, and of course I support the Blunt amendment.”

To be fair, Romney probably was confused, although not in the purely innocent way he claims.

After all, how could he not have recognized “Blunt” and “Rubio” as the names of two Republican members of the U.S. Senate? And Heath did provide a succinct explanation of the Blunt amendment, saying that it “deals with allowing employers to ban providing female contraception.” But instead of seeking clarification, Romney immediately replied:

“I’m not for the bill. But, look, the idea of presidential candidates getting into questions about contraception within a relationship between a man and a woman, husband and wife, I’m not going there.”

The story here, as Adam Serwer of Mother Jones pointed out, seems to be that Romney had never heard of the Blunt amendment before – that he’s been mouthing the words the right wants to hear about Obama’s war on religious liberty without actually knowing (or maybe even caring) what the precise issue is and what Republicans actually want to do about it.

This underscores the popular impression of Romney as someone who doesn’t really believe much of what he’s been saying in his quest for the Republican nomination – and the degree to which the process is compelling him to stake out positions that will haunt him in November. In this instance, the effect is heightened by the venue, Ohio, a state that is suddenly critical to Romney’s nomination hopes (its primary is next Tuesday) and that will also (as always) be a premier swing state in the fall.

Romney is running from behind in the GOP primary, trailing Rick Santorum by double digits according to a poll released earlier this week, which explains why he was so quick and emphatic in clarifying his Blunt amendment position. To say anything else would be to commit political suicide next Tuesday.

But the Blunt amendment, with its open-ended language allowing any employer to refuse coverage of any benefit simply by asserting a moral objection, represents the sort of cultural overreach that has been hurting the GOP as it’s plunged into the contraception/religious liberty fight in the past month. In his initial response to Heath, Romney demonstrated an instinctive understanding of this, expressing broad, reassuring sentiments on contraception that seemed designed for a general election audience. But when he was made aware of the question’s primary season significance, he was forced to bite the bullet.

This isn’t the first time something like this has happened with Romney in Ohio. Just two weeks before last fall’s election, he paid a visit to a Republican campaign office in Cincinnati. Volunteers were making calls urging voters to uphold SB-5, the law curbing public employees’ collective bargaining rights that Gov. John Kasich and Republican legislators had enacted earlier in the year. Their work was clearly going to be in vain; the law was massively unpopular and polls showed it would be overwhelmingly repealed. And Kasich’s approval rating was in the toilet.

Romney’s campaign seemed to grasp the danger; the press wasn’t given a heads-up and Kasich didn’t accompany Romney. And Romney seemed to grasp the danger too, awkwardly refusing to tell reporters who were there whether he supported SB-5. National conservatives reacted with swift condemnation – declawing public sector unions is one of their top priorities – leading Romney to insist he was an ardent SB-5 backer and to apologize for any confusion.

SB-5 and contraception typify the politically poisonous direction that the GOP has moved in the Tea Party era. Republicans had it easy in 2010, with rampant economic anxiety amplifying the electorate’s normal midterm tendency to vote against the White House party. But since then, the GOP has used its new power in Washington and in statehouses across the country to pursue the agenda of its Tea Party base, putting the party on the wrong side of public opinion on a host of sensitive subjects.

This is the real reason it’s such bad news for Romney that the primary season is dragging on. He’s still very likely to win the nomination, but until he does, he’s going to have to keep taking positions that will give his general election opponents real ammunition.

Shares