The 2012 presidential campaign is shaping up into a clash of economic visions. In response to the escalating GOP criticisms of his fiscal policies, Barack Obama has recently dialed up his own rhetoric, defending programs from financial reform to the auto bailout and the stimulus, and castigating conservatives for their “you’re-on-your-own” economics. In this conservative vision, markets are seen as the best guarantors of freedom, and the most effective means of organizing society. State interference is deemed corrupt, ineffective and a threat to personal freedom. This framework has driven successive conservative attacks on financial reform, workers’ rights and efforts to expand the social safety net.

But as the earlier essays in this series have shown, this right-wing view has also influenced progressive policies. In recent years, progressives have been more inclined to support privatization of state functions like prison management, to view equal opportunity in terms of a market-competition for increasingly scarce jobs, underinvesting in worker rights, and using a rhetoric overly friendly to financial interests. If progressives want to affect substantive change these areas, they need to do more than come up with policy ideas. They need to reclaim the language of freedom.

Despite conservative rhetoric to the contrary, freedom is more than individual freedom from state interference, or the freedom to transact on the market. Throughout history, successful progressive reformers have espoused a much more robust view of freedom: one that combats not only the arbitrary power of the state, but also the threats posed by powerful private actors like big corporations, and by the inequities and insecurities caused by market fluctuations. In this vision, the government is not an obstacle to freedom that must be dismantled; rather it is a vital tool that can help expand individual freedom against the dangers posed by big private interests or economic insecurity. This progressive view of freedom is also a deeply democratic one: We are free when we can act as politically empowered citizens, holding government accountable, and pushing the state to create a more just economy.

This progressive view of freedom was most clearly articulated by a disparate set of reformers around the turn of the 20th century. Their world was shaped by the nation’s radical transformation in the wake of the Industrial Revolution. The stunning growth of corporations created powerful new companies like the Standard Oil Trust and financial giants like J.P. Morgan. Meanwhile increasing urbanization, poverty and social displacement combined with recurring boom and bust economic cycles to create a new level of economic insecurity.

The anxieties caused by this emergence of the modern industrial market economy fueled an explosion of reformist political activity. From the rural Populist Farmers Alliance to urban reformers, antitrusters and a new cadre of professional lawyers and economists, the period from 1880 to 1920 marked one of the most vibrant and active areas of reform and innovative thinking about the basic structure of the economy and American politics. Although the Progressive movement was multifaceted and diverse, these reformers shared a common set of responses to the challenges of the new economy – views that are crucial to consider in today’s debates over state regulation, economic revival and democratic reform.

Progressive reformers faced three major obstacles. First, there was the problem of concentrated private power: large corporations, trusts and monopolies. The vast sums of money and market dominance of railroads, financial firms and industrial factories made it obvious that these corporations could use their power arbitrarily or self-interestedly, to the detriment of individual citizens and the public good. What chance did a small businessman have for fair credit, or a farmer for good prices, or a worker for fair wages in an economy dominated by powerful and largely unaccountable firms like J.P. Morgan and the railroad monopolies?

Second, even apart from these various monopolies, the new economy itself created enormous instability. Fluctuations in commodity prices affected both producers and consumers, and wages were similarly volatile. Individuals found themselves in a more precarious position than ever, increasingly dependent on wage income, yet increasingly susceptible to ill health from pollution or workplace accidents.

These problems were magnified by the third challenge facing of Progressive Era reformers: political corruption. At precisely the time when citizens were mobilizing in favor of policies to protect workers’ health, safety and economic opportunity, it was becoming increasingly clear that the state was incapable of responding to these needs. Muckraking accounts of legislative corruption highlighted how big business had captured state and federal legislatures. Meanwhile, a conservative Supreme Court struck down reform efforts such as the workday regulations revoked in the infamous 1905 case of Lochner v. New York.

So these economic challenges became political ones: The prospects for reform depended on overcoming political constraints of corruption, disparities in political power, and the conservative Supreme Court. As a result, Progressive Era reformers developed a rich array of social and political innovations designed to expand the political influence of ordinary citizens. First, reformers coordinated through a wide range of associations. The period from 1880 to 1920 saw a rise of farmers cooperatives, women’s leagues, trade unions, manufacturers organizations and professional associations. Such associations helped educate ordinary citizens about issues of the day, which in turn made them more adept at asserting their own political interests against wealthier and more established groups. In addition, many reformers tried to expand the powers of local governments, in the hopes of creating an alternative space in which to experiment with new social policies. These efforts helped give rise to the Home Rule movement, which aimed to grant municipal governments basic powers to make social policy without state approval.

Progressives were also the driving force behind early regulation experiments, supporting the creation of state agencies to oversee industries such as the railroads and other trusts. At the federal level, these debates led to the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission and later the Federal Trade Commission. Although both agencies faced stiff opposition from the Supreme Court which routinely narrowed the scope of regulatory power on antitrust issues, these efforts helped set the stage for the New Deal. At the state level, rate commissions and other forms of regulatory oversight of the economy became more common. Finally, at the local level, progressives engaged in a spirited effort to develop systems of public utilities. From transportation systems to water provision, reformers argued that private monopolies in these necessity-providing industries undermined the public good. Through unique municipal oversight, and in some cases outright public ownership, progressives tried to deploy the powers of the states to ensure that basic necessities were provided effectively and fairly.

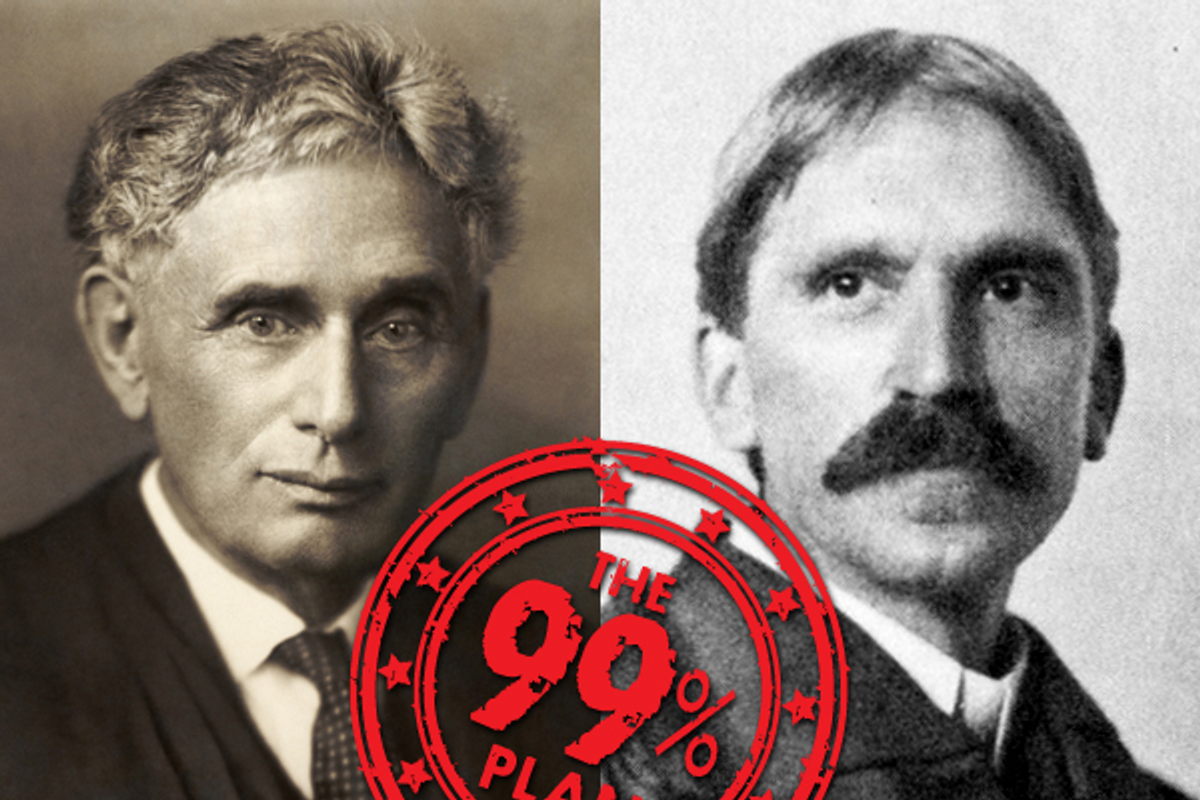

The common thread running through these disparate reform efforts was a distinctly progressive view of freedom that contrasted with the free-market views of conservatives. This vision was most clearly articulated by Progressive Era thinkers such as the philosopher and activist John Dewey, and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis.

For both Dewey and Brandeis, freedom meant more than just individual autonomy and free market exchange. Instead, freedom was achieved when citizens were able to live meaningful lives. In the modern economy, creating this sort of freedom meant enacting public policies that would protect individuals from extreme insecurity and exploitation.

First, this required a robust welfare state, providing social insurance so that, in Brandeis’ words, citizens “may live and not merely exist.” Freedom was threatened by unrestrained competition that created unacceptable risks for individual incomes and basic well-being. To protect freedom, then, required social insurance and minimum standards for wages, health and safety.

Second, there had to be regulations and oversight to place checks on the power of large corporations, for such powerful private actors could dominate workers, extract unfair profits from consumers, and corrupt the political process itself.

Third, these freedom-enhancing policies had to be paired with greater political freedom in the form of direct citizen participation. For both Dewey and Brandeis, freedom meant that citizens were empowered to participate in politics, hold government officials accountable, and help drive new policies. As a result, both thinkers emphasized the mobilization of citizens in associations like labor unions, and the importance of policymaking at the local level where citizens could engage directly with the political process and hold the government accountable.

In today’s world where most citizens are increasingly disempowered—at the mercy of big corporations, the vagaries of the market economy, and the corruption of public officials—freedom has to be more than just the conservative view of freedom from the state and freedom to transact in the market. Instead, the progressive view of freedom expands the power of individuals themselves, by protecting them from private interests and insecurity, while giving them a more direct voice in government. This vision requires a different rhetoric than what is commonly used by progressives in politics today. But it also requires policies that go further in expanding the social safety net, overseeing big corporations from Wall Street to BP, and expanding the opportunities for direct citizen participation in government. This election offers an opportunity for progressives to revive this view of freedom—and in so doing, to catalyze a longer-term movement for a more just economy.

Shares