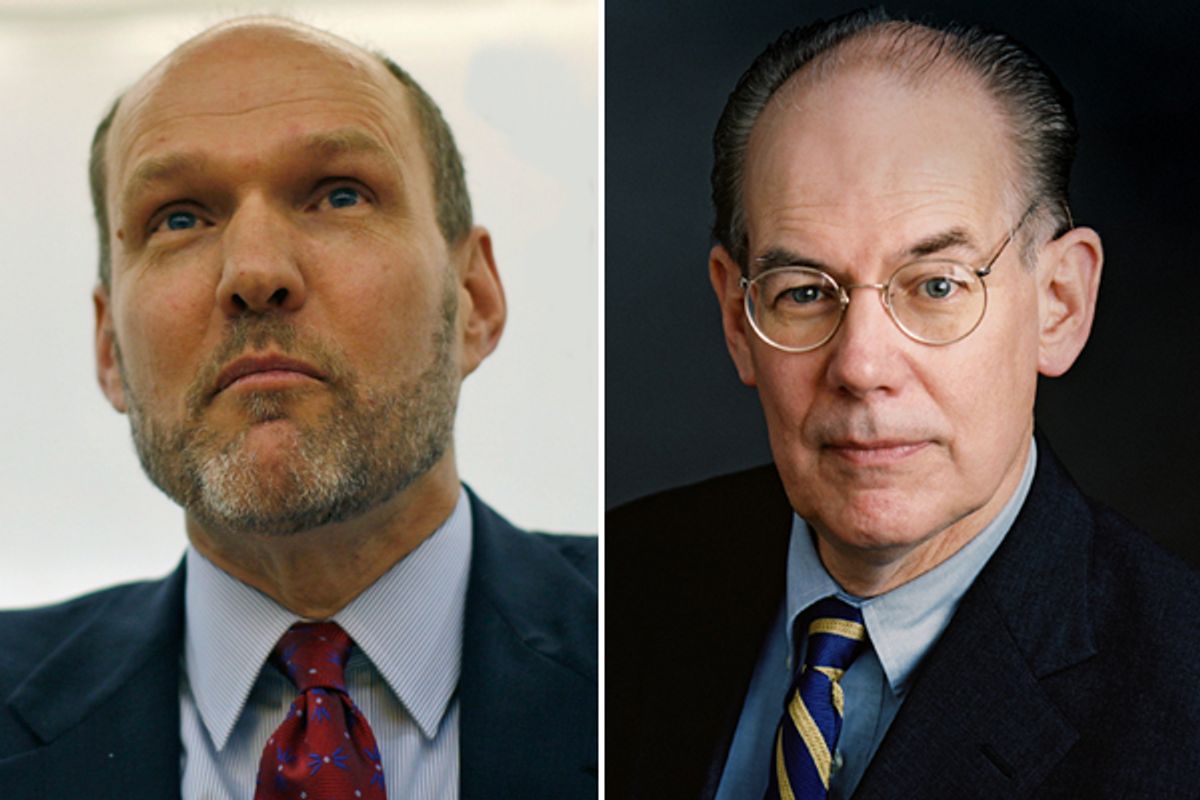

Before they became famous — or infamous, depending on one’s perspective — for their article (later turned into a book) called "The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy," professors Stephen Walt and John Mearsheimer were best known for their prescience about the Iraq War. Right before the U.S. invasion in 2003, they called it “an unnecessary war” and said Saddam Hussein’s “nuclear ambitions -- the ones that concern us most -- are unlikely to be realized in his lifetime.” They even spent $38,000 to place an ad in the New York Times saying that that war would not serve America’s national interests.

But the controversy over their depiction of the Israel lobby overshadowed their foresight about Iraq, unfortunately. Lest anyone think they would avoid the issue in the future, however, Walt and Mearsheimer are back with their first jointly written piece since they responded to critics of their Israel Lobby thesis. On Monday they published an Op-Ed in the Financial Times once again locating Israel at the heart of U.S. foreign policy and and once again seeking to stem a campaign for war, this time in Iran.

“Mr. Obama should continue to rebuff Israel’s efforts to push him into military confrontation with Tehran, while reminding [Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu the true danger to Israel lies in its refusal to allow a viable Palestinian state,” Walt and Mearsheimer write. “If the US and Israel had a normal relationship, Mr. Obama could make his disagreements with Mr. Netanyahu plain, and use the bully pulpit and America’s substantial leverage to help Israel rethink its course.” Alas, they note, the Israel lobby prevents Obama from exerting his authority over what should be a client state.

Walt and Mearsheimer speak for an entire class of long-silenced voices in Washington's policy debates: the realists. These are the men and (a few) women who were prominent in the Eisenhower, Nixon and George H. W. Bush administrations, but who have been marginalized with the GOP’s hard-right turn. They believe the United States should narrowly define its national interests, but they also believe America itself has to be restrained, which makes them opposed to the promiscuous use of force.

Here we have Robert Merry, editor of the National Interest, where many of the realists are housed, warning against a war with Iran. The Washington Post published a full-page advertisement this week, paid for by the National Iranian-American Council (NIAC), which took the form of an open letter to President Obama warning him against war. It was signed by eight former U.S. military and intelligence officials, including Colin Powell’s former chief of staff, Col. Lawrence Wilkerson, and Paul Pillar, a former senior CIA analyst, who amplified his views in the Washington Monthly. If Washington has an antiwar movement opposing an attack on Iran, today, these conservative thinkers are in its vanguard.

I spoke with Walt and Mearsheimer, separately, about why they decided to reenter perhaps the most delicate ring in the American political debate. The Op-Ed came about because the British-based FT asked the two political scientists to write it.

“I think it is extremely unlikely that the New York Times would ask us to write such a piece,” Mearsheimer said. “It’s hardly surprising that a newspaper outside the United States asked us to write on Netanyahu’s visit, and an American newspaper like the Times or the Washington Post did not.”

Indeed, though Mearsheimer was a frequent guest on the Op-Ed pages of those papers before "The Israel Lobby" was published, he has not appeared since. There has not been a complete media freeze-out, though, as Walt writes a popular blog for Foreign Policy, and Mearsheimer was just the subject of a positive profile in the Atlantic recently. Walt was recently asked to write a piece for the Post’s Outlook section (though, notably, not for its more conservative Op-Ed pages).

Walt and Mearsheimer say the current debate in Washington over Iran is entirely wrong-headed. They think the world would be better off without an Iran buttressed by nuclear weapons, but they believe both that Iran has not made the decision to become a nuclear weapons state and that a nuclear-armed Iran would not be a serious security threat to either the United States or Israel.

“It doesn’t tell you very much to say that Iran is a national security threat to the United States -- the question is how serious a threat is it?” said Mearsheimer. “The answer is that it’s not a serious threat. Even if Iran did have a nuclear weapons capability, they could not use that to blackmail the United States or to attack; the United States has a retaliatory capability, so Iran is a minor threat at best.”

A nuclear-armed Iran would not even be a serious threat to Israel, he argues: “For all good sorts of security reasons, Israel wants to remain the only nuclear power in the Middle East, but a nuclear-armed Iran could not attack or credibly threaten to attack Israel, any more than it could the United States, because it has a retaliatory capability.”

Here Mearsheimer is relying on his long-held belief that nuclear weapons are usually a stabilizing force in world affairs. In 1990, he wrote that nukes are “more useful for self-defense than for aggression. If both sides’ nuclear arsenals are secure from attack, creating an arrangement of mutual assured destruction, neither side can employ these weapons to gain a meaningful military advantage.” A nuclear-armed Iran, Israel and the United States would all be subservient to the logic of mutually assured destruction, which successfully kept the peace in the Cold War (though there were many dangerous close calls, which call that theory into serious question).

Interestingly, Walt and Mearsheimer believe that Israel will not attack Iran, and that the United States will not, either. “Israel’s air force capabilities can’t do enough damage to destroy Iran’s nuclear program; they can slow it down but they can’t stop it,” says Walt. “Neither can we, although we can do a lot more damage.” Additionally, Israel has consistently gotten a message from the United States saying it is opposed to a war, and it would be wary of doing something America has explicitly told them not to do. “They would like to keep rattling sabers on the issue to focus attention on the issue, bring the United States into it, and get backing from the Europeans on sanctions, but at the end of the day, I don’t think they will do it.”

Here Walt and Mearsheimer may be guilty of naiveté. Countries routinely take actions that seem illogical and senseless to others. The widely predicted futility of invading and occupying Iraq did not stop the United States from doing it; from trying to rebuild medieval Afghanistan, or from trying to destroy Vietnamese nationalism in the 1960s, for that matter. Nor did the foreseen impossibility of destroying Hezbollah prevent Israel from making war on Lebanon in 2006.

If Iran fails to back down from its nuclear program — and only miraculous diplomacy could achieve such a thing — Israel may simply decide that trying and failing to militarily stop Iran’s nuclear program is better than not trying at all. Netanyahu’s frequent references to Iran as potentially being a second Nazi state may be saber-rattling, but it may also reflect a worldview that a second Holocaust, however remote a possibility it appears to others, cannot be risked.

For Walt and Mearsheimer, diplomacy still offers the best hope for peace in the standoff. “I could make a good argument that it would be in Iran’s interests not to have nuclear weapons, but not if they are constantly being threatened with an attack or occupation or regime change,” says Walt. Threatening to attack Iran, paradoxically, is the one thing that would convince them that they need nuclear weapons — to protect them from the very attack that is designed to prevent them from getting nuclear weapons.

“This dispute could be resolved through diplomacy, and I think it would involve the United States agreeing that Iran could have a nuclear enrichment capability, under the terms of the non-proliferation treaty, with robust inspections; and Iran would be pledging not to have nuclear weapons, and we can work on addressing the other issues,” says Walt. If diplomacy is given time to work, that is how such a thing would play out.

There was a great missed opportunity for diplomacy with Iran at the outset of the Obama administration, Walt and Mearsheimer believe. “The administration barely outstretched a hand,” Mearsheimer says. They argue that real diplomacy takes a long time, and that the administration was not sufficiently committed to the program to give it time to work. Here they echo National Iranian-American Council president Trita Parsi’s recent book "A Single Roll of the Dice," which argues that the Obama administration rushed its diplomacy and made important mistakes (although Parsi blames Iran for similar miscalculations). Notably, however, Parsi believes only that there are elements within the Iranian government that want a deal with the United States — other elements do not.

Even if diplomacy didn’t produce a grand bargain, however, Walt and Mearsheimer believe a military strike would be disastrous for the United States, and what’s worse, it wouldn’t be successful. “Even if we somehow destroyed all of Iran’s nuclear capability, they will simply rebuild it, in locations that are harder to find and harder to destroy,” says Mearsheimer. “At best, even a successful strike buys you a few years. It only delays the problem. There is no military solution to this problem."

Shares