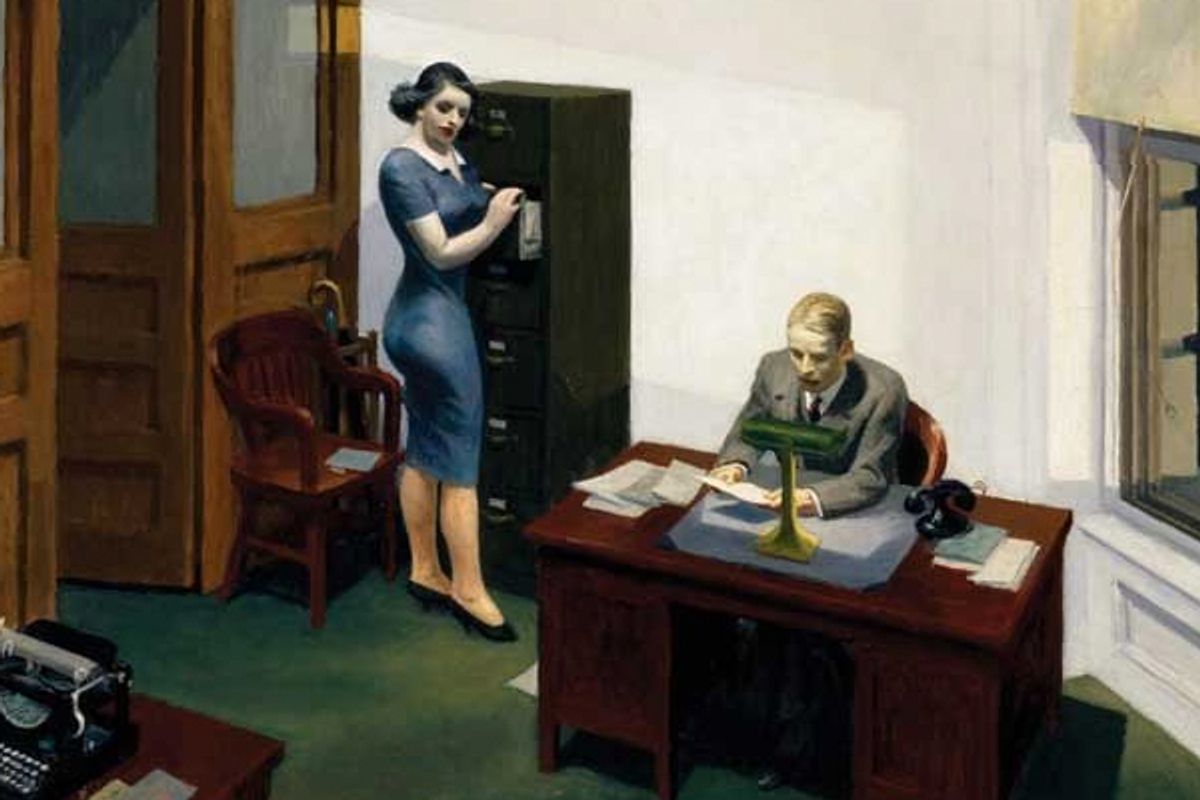

These days, it’s impossible to discuss sex in the office without immediately thinking of sexual harassment. The term shows up everywhere, from the campaign trail to, most likely, your nearest office cubicle. But the concept of inappropriate sexual behavior has evolved dramatically since the 1860s, when women first took jobs as clerks in the U.S. Treasury office. Over the past century and a half, people of both sexes have gradually rethought what is and isn’t appropriate sexual behavior in professional environments -- a transformation that has paralleled dramatic reconfigurations in our conceptions of gender, equality and work itself.

In her new book, “Sex and the Office: A History of Gender, Power, and Desire,” Julie Berebitsky, professor of history and director of the Women’s Studies Program at Sewanee University and author, previously, of “Like Our Very Own: Adoption and the Changing Culture of Motherhood,” explores a vast array of sources, including advertisements, advice guides, archival sources and actual experiences of male and female office workers, to better understand which of our attitudes have changed, and which have stubbornly remained the same. It's a dramatic reminder of the fact that men have claimed to be hardwired for sex -- and women have been accused of being temptresses seeking special favors -- long before Herman Cain and Clarence Thomas.

Salon spoke with Berebitsky over the phone about the evolution of sexual harassment, whether romance in the office is actually allowed, and the future of gender equality in the workplace.

Who coined the term "sexual harassment"? Why was there a need for the term then? How has sexual harassment in the office evolved since the term was coined?

Sexual harassment, the term, was coined in 1975 by a group of feminists at Cornell University who were working in the human relations office. They encountered a woman who had been sexually harassed in one of the science departments by her boss. He was doing things like putting his hand up her dress at office parties and trying to corner her. She was so distressed that she ultimately quit her job. When she couldn't find another job she tried to apply for unemployment insurance but was turned down because they said she hadn't quit for cause, she should have put up with her boss’s behavior. She complained to human affairs at Cornell where there were a number of feminists working. They had the first speak-out against sexual harassment in 1975 and the coin was termed. It became a term that activists and women could unite around and turn into a social movement. I argue that one of the reasons why it didn't become a social issue before the 1970s is that it was too difficult for women who occupied a marginal place in the labor force to come forward.

How has it changed since then? How has sexual harassment in the office evolved since the 1970s when the term became something defined and a movement?

Laws have changed things dramatically. In 1986 the Supreme Court in Meritor v. Vinson declared quid pro quo sexual harassment and hostile environment sexual harassment to be a violation of Title 7. Certainly things have changed dramatically since then, especially in terms of quid pro quo sexual harassment, which is where bosses give favors or wield power in return for something sexual. That type of sexual harassment has dropped dramatically as companies have instituted various policies and awareness programs. Things have changed less in what's referred to as hostile environment sexual harassment. Here, there’s a certain discourse that women are overly sensitive, that women are making things up, that sometimes women are using an accusation of sexual harassment to get back at a man. Overall there's still a good deal of distrust towards women. After Herman Cain, the Washington Post did a survey where men were asked, "Are you worried about a false accusation of sexual harassment?” Fully one-quarter of men that were questioned said yes. So there's still this belief that women lie.

You wrote that “Sex and the Office” isn’t so much a history of sex and the workplace but an attempt to answer the question: Who really needs protection from the predatory intentions of the opposite sex—women or men? This is the question that Americans have been debating since the early 19th century. What’s the answer?

I believe sexual harassment is about power. And I believe that sexual harassment is a form of discrimination because the way it works keeps women out of certain positions. It's a given that men occupy powerful positions in the workplace. I think women are in more need of protection. I don't deny that women can harass. And certainly there's real harassment against gays and lesbians which is a whole other part of the problem—that anyone who doesn’t fit our gender norms can find him or herself under attack—so I think that we need to keep thinking about how our cultural values and a distrust of women in sexual matters work together to keep women down. For example, this whole notion of women as sexual temptresses existed from the minute women first entered the office to the present. Lots of successful women talk about how they have to worry if they're promoted too quickly or if there's a hint that have any sort of relationship with the man in charge, they're going to get tagged that they slept their way to the top. We believe men are sexual creatures and that their sexual behavior, even when inappropriate, is natural. “The Male Brain” by Louann Brizendine M.D., has a chapter titled, "The Brain Below the Belt," in which she says that men are hardwired in this sexual way. I think on one hand we have a cultural stereotype that women use their sexuality to take advantage of men's sexual vulnerability. On the other hand we have: Men, that's just the way they are sexually. I think those two cultural discourses hurt women more than they hurt men.

Why did you choose to focus on harassment of women working in white collar offices as opposed to institutions like schools, factories, hospitals, and private homes that have a longer history of employing women?

One of the things that makes the office so different is that it was widely understood that women and men who worked in the office were middle class. Already in the late 19th century people were saying: "Factory owners are coarse men, they might try to extort sex from the women who work under them, but middle class businessmen wouldn't." I thought that was an interesting issue to examine. By the 1950s, a majority of American women who worked outside the home were employed in white collar jobs. I was interested in looking at cultural representations of behaviors that we would now define as sexual harassment. There are so many films about the white collar workplace, so many pieces of fiction about it, that it really allowed me to expand beyond the study of a more factual "this is what happens to women" approach, and also to talk about cultural representation. People always saw unwanted behaviors as the flip side of wanted behaviors. So we see sexual harassment as something distinct, but historically Americans haven't made such a rigid distinction. It was just all part of the culture of the office.

Do women take the majority of the blame during instances of sexual harassment at work? If so, why do you think that is?

Before the 1970s, the only time that there had been widespread concern about sexual harassment was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries when many people were saying middle class women were without sexual desire. So here we had these passionless women working in offices in one-on-one situations with men: Will those men take advantage of those women?

Even as some reformers were talking about that, we already had a kind of counter discourse that said, "No, these office women are lust pirates who will destroy a businessman's marriage. Women use their power over men to get a day off or easier workload." By the 1920s, that desire to protect women completely vanished. What we see happen historically is that in the 1920s society started to acknowledge that women have sexual desire. At that point it became expected that the modern working girl in an office would know how to handle a man's attention. If you look at guidebooks in the '20s and '30s designed for women workers they say: “It's likely you'll encounter a Felix the Feeler, but it’s your job as a modern woman to know how to handle him.” They also advise: "if you can't deal with Felix the Feeler on your own, you're going to have to quit because men are the valued employees." In addition, you see the rise of psychiatry, which diagnoses these men as suffering from a midlife crisis. The problem with that is it says: "This is temporary behavior; we as a society don't need to see it as a social problem. This man is going through a midlife crisis, eventually he'll come out of it, and meanwhile the modern girl should be able to handle it." It absolves the man for any responsibility and says it's up to the woman to handle his behavior.

Can you talk a little bit about what happens to a woman in the workplace once she's accused a co-worker of sexual harassment?

I'm a historian, not an attorney, so this is a place where I'm not quite as confident in my analysis. If an employee accuses a co-worker of sexual harassment, she can take it to her employer and see what he would like to do. If she signed a contract that said: "If I have any problems I agree to solve it through confidential arbitration," then it would become an in-house process decided through arbitration and she would have to live with the results. This came up with Herman Cain, the arbitration and confidential settlement. If she hadn't signed that contract she could file a claim with the EEOC (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) which is the central agency that is charged with enforcing Title 7, which makes sexual harassment illegal. About 12,000 claims are filed each year. The majority of those EEOC cases are settled out of court through arbitration. And then the other option would be to file a private civil case. A lot of men and women still quit.

You mentioned Herman Cain. Presidents Kennedy and Clinton have been accused of sleeping with interns. Do you think that the political office is more prone to sexual harassment?

No, not at all. I think that those cases get a lot of publicity. It's an understanding that powerful manhood includes sexual access to women. That version of masculinity encourages sexual harassment in some ways. In the 1950s, there was a big scandal where General Electric and other businesses -- Edward R. Murrow did an expose of this -- were using prostitutes to close deals. And it was just what it meant to be a white collar man. My argument in part is that our cultural understanding of masculinity for businessmen and politicians, that realm, is all about sexual success with women. Sex is part of our understanding of successful men.

In addition to gender in the workplace, you write about race. African-American women were prominent in the first efforts to use the new sexual harassment laws. Why was this group on the forefront?

Most scholars argue that African-American women, because of their experiences of racism and the long history of African-American women sexual assaults from slavery to the present, were more sensitized to the issue and saw it as something that was about power and discrimination before many white women did.

How are other industrialized countries dealing with unwanted sexual attention at work?

France has a different attitude towards sexual attention. It's not handled legally in the same way, it's not considered discrimination. All industrialized nations are tackling the problem in some way, and in the last couple of years people have been talking about sexual harassment in India as more and more women enter the labor force there. I think all industrialized nations have certainly acknowledged sexual harassment. Going back to the notion of culture, sex is treated differently in every place. The French, for example, think the U.S. treatment of sexual harassment is crazy, that of course there are going to be romantic relationships in the workplace, that's just the way things are. Certainly there are prohibitions against sexual harassment in France, but they think we've taken it too far.

How do you respond to critics of sexual harassment laws, like Katie Roiphe who wrote in the New York Times, “In our effort to create a wholly unhostile work environment, have we simply created an environment that is hostile in a different way?”

I don't think she takes it very seriously. Roiphe and others are not really critical of hostile environment sexual harassment. The people who dismiss it always return to the idea of women being overly sensitive or that women just can't take a joke. In fact, the examples of hostile environment sexual harassment that I've found are not minor incidents. The thing to remember is that it's actually quite difficult to make a sexual harassment claim. At most, 5 to 15 percent of women who experience sexual harassment legally do anything about it. And of those 12,000 cases that the EEOC investigates each year, only about 50 percent are found to have any cause. There’s this unfounded notion that we’re all living in fear of sexual harassment and feminists are making mountains out molehills. These instances are not trivial. One incident in the early 1970s was when a secretary has a co-worker who keeps asking her out. She tells her employer he's hassling her, the employer tells the man to cool it. But he really doesn't. It goes on for a number of months, six or eight, until she comes back to her desk after lunch and finds a glass soft drink bottle covered in vaseline, dead flowers in it, and a rambling completely discombobulated note. I think most women would assume that as a threat of rape. In my opinion, men should not be allowed to do that in the workplace. A way to ensure they don't is to make it illegal. I’ve seen evidence from the late 19th century to the present of bosses who call in their secretary to take dictation and dictate sexually explicit material that has nothing to do with the business at hand, just to watch the woman squirm, to get a thrill. I found a couple of examples where the boss calls the secretary into the office, and he drops his pants in front of her. It's so bizarre, but it happens. It happened historically, it happens now. We need to take it seriously.

What does the future look like for sex and the office? Will there ever be gender equality in the workplace?

Yes. Someday there will be gender equality in the workplace. The thing to know about sexual harassment is that feminists are not anti-sex. What they are trying to do is create a workplace in which consensual sexual relations are possible, but all of the coercive ones are gone. Where a power element didn't color relationships in the office. Feminists are not really against consensual sex, they're skeptical about relationships in which there's a distinct power differentiation. But the idea is for men and women to be able to work together as equals who are able to enter into romantic and sexual relationships as equals. We just need to get rid of the unwanted and unwelcome relationships that work against gender equality.

Shares