Carl Cameron of Fox News reported Sunday night that Newt Gingrich’s campaign has been engaged in “preliminary ‘what-if conversations’” with Rick Perry’s camp about teaming up as a ticket in advance of this summer’s Republican convention.

The idea, supposedly, is that anointing Perry as his V.P. might help Gingrich corner the market at a deadlocked convention on religious conservatives, Tea Party supporters, and Southerners. An alternate reading, as Cameron notes, is that Gingrich’s side could be floating the rumor as a way of increasing their candidate’s appeal in Tuesday’s Mississippi and Alabama primaries, which Gingrich has admitted are do-or-die tests for him. It’s also possible there’s absolutely nothing to the story. Perry’s spokesman calls it “humbling but premature,” while Gingrich’s swears there’ve been no conversations “at any level” between his camp and Perry’s.

That this kind of story attracts any attention is a consequence of the deadlocked convention talk that won’t quite go away. The odds that the GOP presidential nomination won’t be settled well in advance of the late-August convention in Tampa are slim, but they’re not entirely nonexistent – something we haven’t been able to say at this point in most previous cycles. And if Gingrich manages to win in Dixie this week, it will bolster the most plausible deadlock scenario that now exists – meaning we’ll probably hear a lot more about possible strategically preemptive V.P. selections by the candidates in the weeks ahead.

At least that’s what’s happened in the few modern campaigns where suspense – or the illusion of suspense – has lingered through the primary season:

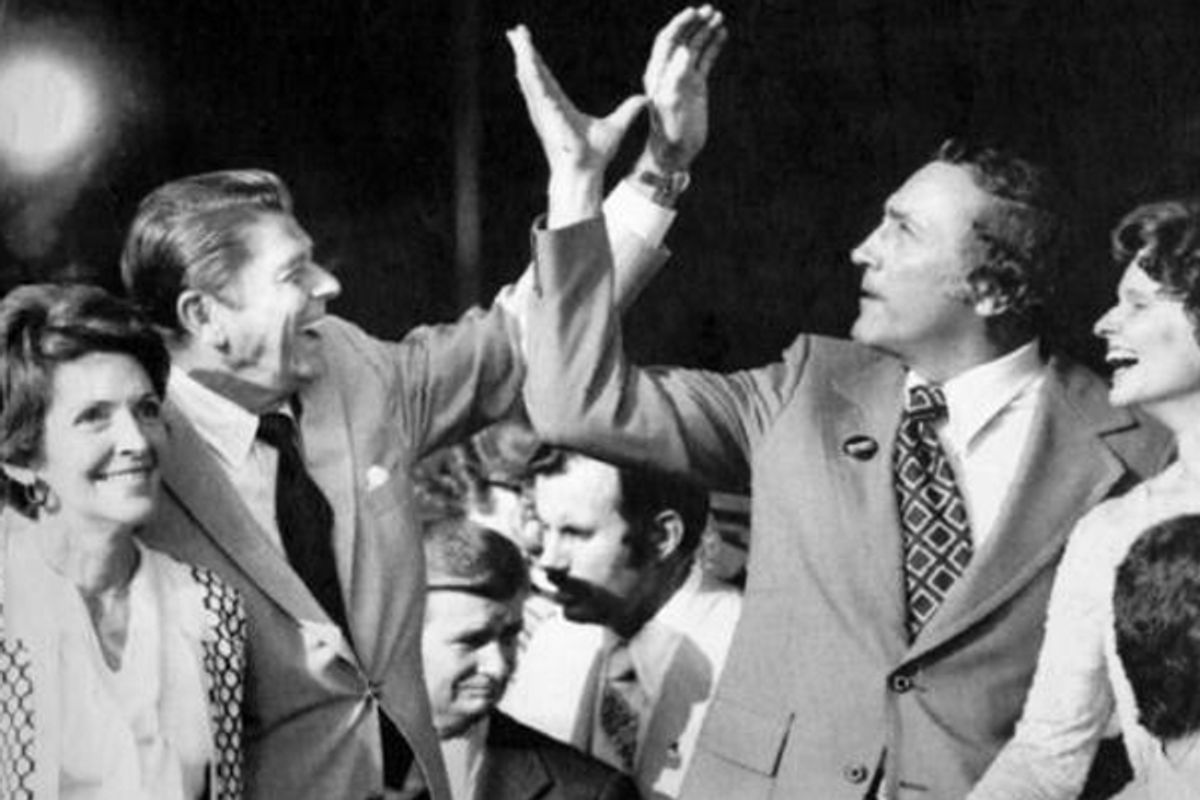

1976

Ronald Reagan fell far behind incumbent President Gerald Ford in the early GOP contests, but turned his campaign round with a surprise win in North Carolina. The primaries ended with each candidate short of an outright delegate majority, and Ford slightly ahead. As the August convention in Kansas City approached, Reagan unexpectedly announced that Richard Schweicker, a moderate senator from Pennsylvania, would be his V.P. choice if nominated. This was supposed to broaden Reagan’s base and win over delegates from the Northeast, but instead it infuriated his core conservative supporters from the South, and gave party leaders in Mississippi a reason to turn on Reagan and align their delegation with Ford. Reagan made no corresponding gains in the Northeast to make-up for the Southern defections, and Ford won on the first ballot 1,187 to 1,070.

1980

Like Reagan in ’76, Ted Kennedy fell far behind President Jimmy Carter early in the Democratic race, but closed with a kick. Still, when the final primaries ended in June, Kennedy was about 600 delegates behind and Carter seemed to have the majority he needed. But Kennedy refused to quit, believing that Carter’s sinking poll numbers – the bounces from the November ’79 Iranian embassy siege and the ill-fated April ’80 hostage rescue effort were finally wearing off – would give Democrats reason to dump him at the New York convention.

So Kennedy spent the summer months asking delegates to overturn the party’s “faithful delegate” rule, thereby freeing them from their first-ballot pledges and allowing them to vote their consciences. Mindful of Reagan’s miscalculation, he played the V.P. game slightly differently, releasing a list of running-mate he said he’d consider: Henry “Scoop” Jackson, a hawkish Washington senator; Tom Bradley, the Los Angeles mayor who was then one of America’s most prominent black politicians; Reubin Askew, an anti-abortion Florida governor; L. Richardson Preyer, a racially progressive North Carolina congressman; Adlai Stevenson, an Illinois senator and the bearer of a famously liberal name; Shirley Hufstedler, Carter’s education secretary; and Lindy Boggs, a Louisiana congresswoman with deep ties to Capitol Hill (her husband Hale, who’d died in 1972, had been the House majority leader).

Kennedy’s gambit may have been too risk-averse. By including a name with resonance to virtually every Democratic coalition group, he seemed to be straining to keep everyone happy and prevent the backlash that Reagan had provoked four years earlier. In any event, it didn’t work, and when delegates convened in Madison Square Garden they rejected Kennedy’s proposed rules change, ending the contest on the spot.

1984

Walter Mondale declared the Democratic race over the morning after the final primaries in June, when he dialed up some superdelegates – then a new breed in Democratic politics – and won enough commitments to hit the magic number. But superdelegate commitments weren’t (and still aren’t) ironclad; they can change their minds anytime they want, and aren’t bound on the first ballot. So Gary Hart refused to concede the race to Mondale, and used the pre-convention period to make the case that he would be more electable against Ronald Reagan.

Hart’s supporters briefly saw an opening when the National Organization of Women adopted a resolution calling for a convention floor fight if Mondale failed to pick a woman as his running-mate. Mondale balked at the threat, and Pat Schroeder, then a Colorado congresswoman and Hart supporter, then publicly suggested that Hart pick a woman himself (She suggested Alice Rivlin, then the CBO director). But many feminist leaders spoke out against the NOW resolution, Hart himself refused to play the V.P. game, and Mondale soon made it all moot by tapping Geraldine Ferraro for the No. 2 slot. The superdelegates didn’t budge, and he and his running-mate were nominated with ease.

1992

Jerry Brown probably never had a shot at the Democratic nomination, but he did have an opportunity to derail Bill Clinton’s campaign. It came in the April 7 New York primary, which became an unexpected make-or-break test for Clinton when he was upset by Brown in the March 24 Connecticut primary. At the time, Clinton was seen as a weak potential nominee after numerous scandals had hit his campaign, and talk was rampant that a New York loss would push him out of the race and prompt party leaders to recruit a white knight candidate.

In what may have been an effort to win support from the state’s large bloc of black voters, Brown began the New York campaign by promising to make Jesse Jackson his running-mate. Jackson, of course, had infamously referred to New York City as “Hymietown” in his 1984 campaign, a remark that created lasting suspicion among Jewish voters, who also accounted for a significant share of the Democratic electorate. When Brown then appeared at a forum sponsored by a New York Jewish group, he was confronted with intense, unrelenting criticism of his Jackson pledge, all as the cameras rolled. As the New York Times reported:

Mr. Brown tried to get back on track by saying the questions over Mr. Jackson were "a graphic demonstration of the split within this community, within this society."

But many in the audience called out, "No," murmuring that there was not a split between Jews and blacks; there was a split between Jews and Mr. Jackson.

Brown ended up finishing third in New York, well behind Bill Clinton (who won with 44 percent) and also in back of Paul Tsongas, who had suspended his campaign but remained on the ballot. Among Jewish voters, the split was: Clinton 55 percent, Tsongas 34, Brown 9. Clinton’s New York victory cemented him as the party’s presumptive nominee.

2008

Since Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama were the only two candidates accumulating delegates, there wasn’t much talk of a deadlocked convention. But as the race dragged on, the V.P. topic was impossible to avoid. In fact, it was just before the Mississippi primary that Clinton, who had fallen behind Obama in the delegate race, seemed to suggest that she’d like Obama to be her running-mate – an offer that Obama was quick to reject. “With all due respect, I’ve won twice as many states as Senator Clinton,” he said. “I’ve won more of the popular vote than Senator Clinton. I have more delegates than Senator Clinton.”

Shares