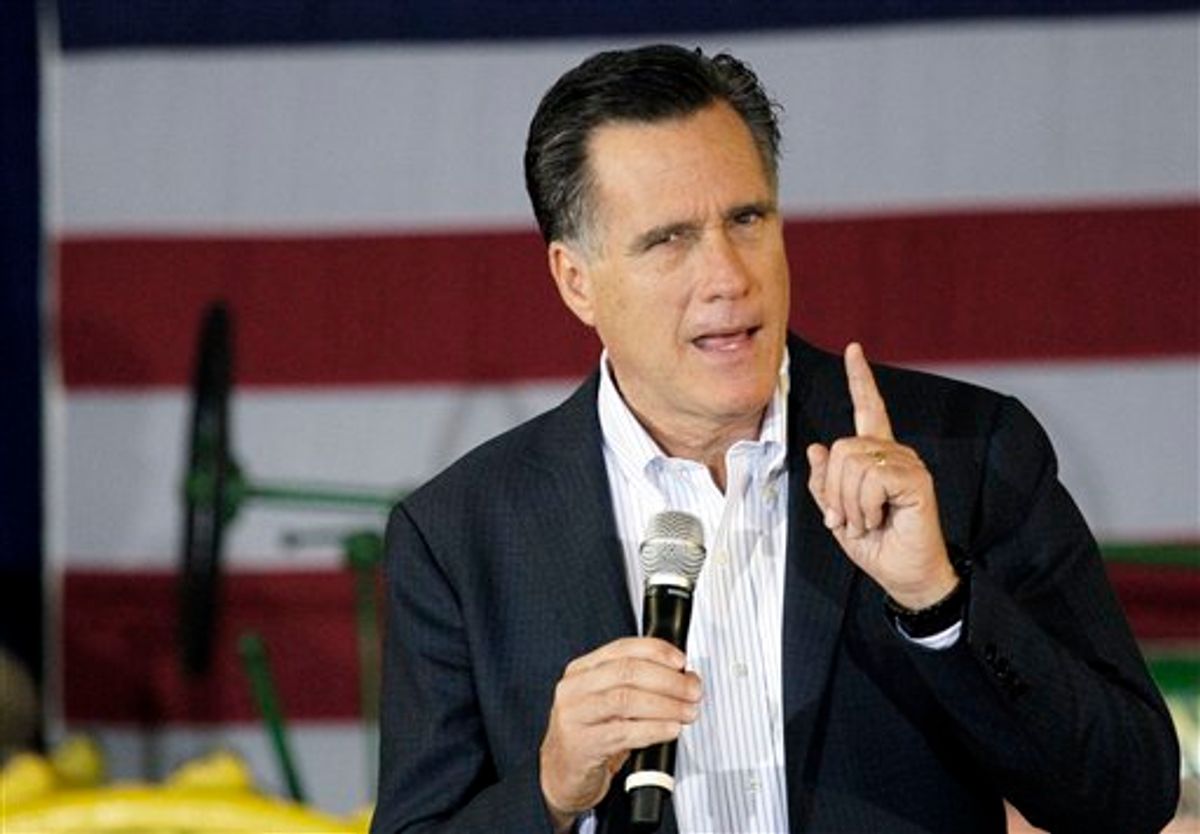

This weekend demonstrated why Mitt Romney’s journey to the Republican nomination is probably as inevitable as it is unsightly.

In the highest-profile contest, Kansas’ caucuses, he was crushed by Rick Santorum, 51 to 21 percent. But because he also scored easy, under-the-radar victories in Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, the Northern Marianas and Wyoming’s county conventions, Romney actually increased his delegate lead over the other candidates.

There’s a view that Romney’s likely emergence as the GOP’s 2012 standard-bearer invalidates the notion that the party’s base has cracked up in the Obama era, or at least proves it’s wildly overstated. After all, would a party driven by rabid ideologues who value purity over electability really choose a former Massachusetts governor with such suspect conservative credentials as its candidate?

In a piece titled "Not-so-crazy Republicans," Ross Douthat made this case in Sunday’s New York Times, arguing that GOP primary voters in resisting the various Romney alternatives have “acquitted themselves about as sensibly, responsibly and even patriotically as anyone could reasonably expect” by methodically rejecting one Romney alternative after another:

Instead, despite an understandable desire to vote for a candidate other than Mitt Romney, Republicans have been slowly but surely delivering him the nomination — consistently, if reluctantly, choosing the safe option over the bomb-throwers and ideologues.

A crazy party might have chosen Cain or Bachmann as its standard-bearer. The Republican electorate dismissed them long before the first ballots were even cast.

This interpretation is especially tempting when you juxtapose Romney’s likely coronation with the 2010 midterm primary season, when GOP voters in several high-profile contests rejected Romney-ish candidates in favor of utterly unelectable fringe characters like Sharron Angle, Christine O’Donnell and Joe Miller.

But the example of 2010 actually points to the major flaw in arguments like Douthat’s: It’s not so much that the party has learned its lesson and evolved since then; it’s that candidates like Romney, who knew from the outset of this campaign that his moderate past and Massachusetts healthcare law would make him vulnerable to the kind of insurrection that elevated Angle and her ilk in ’10, have.

After all, it’s not as if Romney is pitching himself to Republicans as a moderate alternative to the Tea Party crowd. His reputation as a conservative apostate stems entirely from the positions and rhetoric he embraced before his move to the national stage around 2005, and from lingering suspicions that he’s been faking it ever since. But as a candidate for the GOP nomination, both this year and in 2008, Romney has consistently aligned himself with the agenda of the party’s conservative base.

He’s often likened to Nelson Rockefeller, the liberal New York governor who was defeated by Barry Goldwater in the 1964 GOP race, but Rockefeller trumpeted his ideological differences with the Goldwater crowd and thumbed his nose at the right. Romney, by contrast, takes pains to pretend he’s always been “severely conservative” and to give his critics on the right as little ammunition as possible.

This has made it tough for Santorum, Newt Gingrich and every other candidate to gain traction against Romney. Essentially, they’ve been trying to run as the conservative alternative to a candidate who, on paper, is every bit as conservative as they are – and on some issues, even more conservative. It would be a lot easier to incite a grass-roots rebellion if Romney was actually disagreeing with the grass roots on anything.

The story, then, is not really that the GOP base has come to its senses. It’s that Romney has given the base just about everything it wants. His readiness to do so (coupled with the comically poor quality of his opposition) will probably be enough to get him the nomination, but it comes with some potentially serious general election consequences.

In catering to a party that has moved far to the right in the Obama era, Romney has put himself on the record endorsing policies that will make him vulnerable in the fall. For instance, he’s taken a particularly hard-line approach on immigration, calculating that there’s room to his GOP foes’ right on the issue. And a poll last week found that Romney now trails President Obama among Latinos by 56 points, 70 to 14 percent. This has given Obama’s campaign hope that it can win several Western states with rising Latino populations, like Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada and maybe even Arizona, potentially offsetting losses elsewhere.

Or there’s Romney’s support for Paul Ryan’s budget plan, which would effectively end Medicare as we now know it. The plan is an article of faith on the right – and a Democratic ad maker’s dream. And his efforts to distance himself from his own Massachusetts healthcare law, which was crafted when the individual mandate was still considered a conservative idea and before the term “ObamaCare” existed, have made it impossible for Romney to enjoy any kind of advantage on the issue over Obama in the fall.

Appeasing the base has also exacerbated Romney’s image as a weak and spineless panderer. On several occasions, he’s felt compelled to “clarify” comments that conservative opinion-leaders considered alarming. And when Rush Limbaugh called a Georgetown law student a “slut” a few weeks ago, Romney was unwilling to say he’d crossed the line – not when doing so might prompt Limbaugh’s listeners to decide that the rumors are true and that Romney really isn’t one of them.

The reason Romney continues to lose GOP contests is that many conservatives still, despite all of his efforts to reassure them, are refusing to check his name off. But enough of them have come around that he’s in good shape to win the nomination. More important, many conservative opinion leaders have simply kept their mouths shut and stayed on the sidelines, rather than entering the fray on behalf of one of Romney’s opponents. This has also been a triumph for Romney.

In this sense, the conservatives who are backing Romney, or at least not actively obstructing him, are acting very rationally. They want a candidate who will run on a platform that’s to the right of every GOP platform since 1964, he’s told them – and shown them -- that he’s willing to, and they’re now saying, “OK, good enough.”

Shares