Anthony E. Grudin cares about the working class. He also cares – a lot – about Andy Warhol. Not the later Warhol, who pandered to high society celebs, but the younger man, with one foot headed for the galleries and the other still hustling for commercial illustration gigs. Anthony, an assistant professor of art and art history at the University of Vermont, has written articles and delivered symposium papers about that early 1960s Warhol. His interest is in that transition period, as the aspiring fine artist drew fashion items for upscale advertisers while adapting Cokes, Campbell’s, comics and other blue-collar consumer products onto canvases.

I first ran into Anthony while wandering around the 100th annual College Art Association conference, recently held at Los Angeles’ Convention Center. CAA is an organization dedicated to promoting the visual arts: mainly fine art, but also fashion, photography, film, architecture, design, etc. The conference's main attractions are its program sessions, and this year there were nearly 200 of them, typically with five speakers at each.

I first ran into Anthony while wandering around the 100th annual College Art Association conference, recently held at Los Angeles’ Convention Center. CAA is an organization dedicated to promoting the visual arts: mainly fine art, but also fashion, photography, film, architecture, design, etc. The conference's main attractions are its program sessions, and this year there were nearly 200 of them, typically with five speakers at each.

Having multiple options over the four days is a big advantage, especially for non-academic browsers such as myself. Some presentations can test one's endurance, with scholars reading complex, esoteric texts about obscure historical minutiae while showing PowerPoint templated bullet points and diagrams in darkened rooms. And others can be surprising, fascinating and, oh yeah, educational. At one on L.A. art journals I discovered the newly launched East of Borneo, which its editor in chief, Thomas Lawson, described as an “online magazine of contemporary art,” in which a diverse collective of talented writers cover the local scene. And at a punk rock session I enjoyed a discussion of dadazines and saw a spirited film created by one of the presenters, Cinthea Fiss, that honored Bruce Conner, the late, underappreciated grandaddy of avant garde music videos.

Having multiple options over the four days is a big advantage, especially for non-academic browsers such as myself. Some presentations can test one's endurance, with scholars reading complex, esoteric texts about obscure historical minutiae while showing PowerPoint templated bullet points and diagrams in darkened rooms. And others can be surprising, fascinating and, oh yeah, educational. At one on L.A. art journals I discovered the newly launched East of Borneo, which its editor in chief, Thomas Lawson, described as an “online magazine of contemporary art,” in which a diverse collective of talented writers cover the local scene. And at a punk rock session I enjoyed a discussion of dadazines and saw a spirited film created by one of the presenters, Cinthea Fiss, that honored Bruce Conner, the late, underappreciated grandaddy of avant garde music videos.

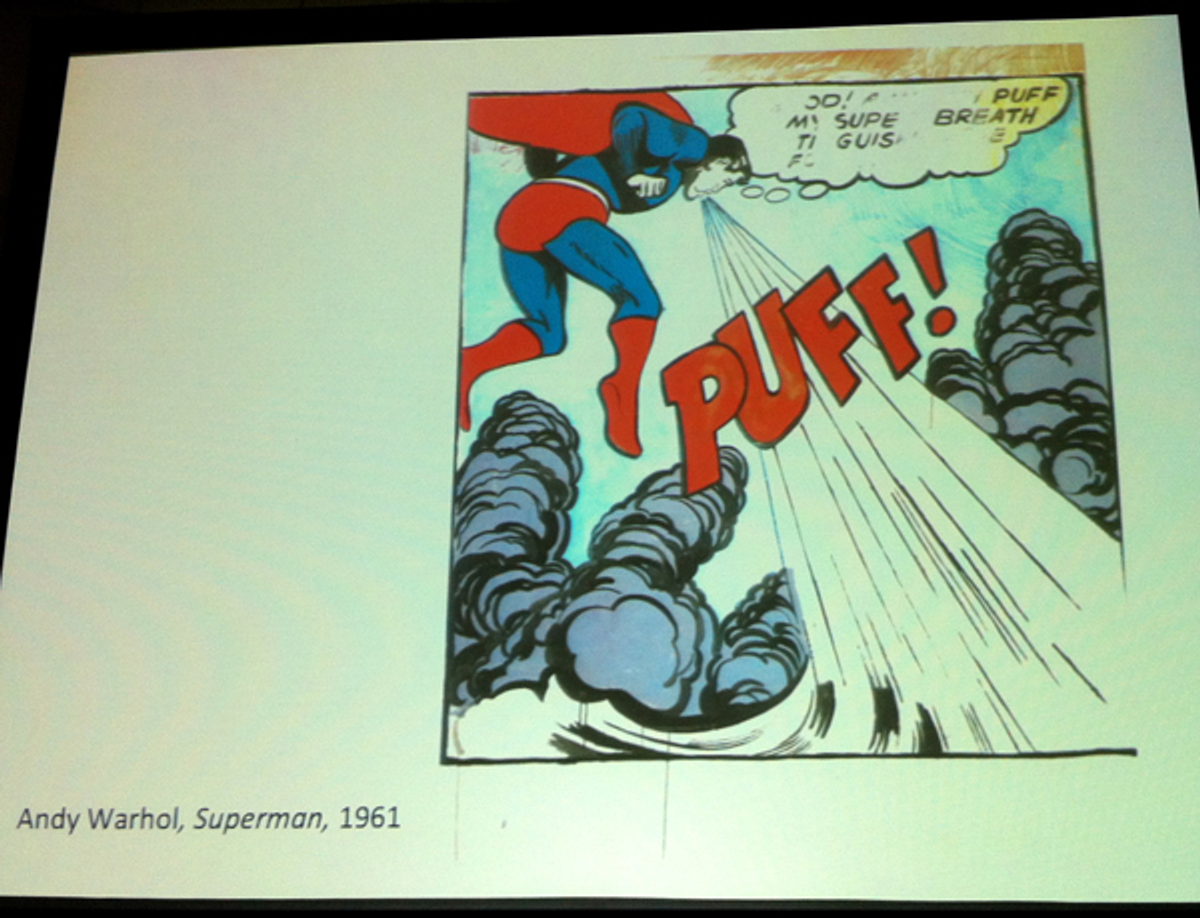

Anthony was the first up for a session titled "Pop and Politics." He titled his talk “Magic Art Reproducer,” after a device to help kids learn to draw. Anthony wove a narrative outward from Warhol’s groundbreaking 1961 "Superman" painting, around various amateur art practices of the era as seen in comic book ads, and into the lives of working-class people. His visuals, which incorporated panels and pages from a variety of sources, helped to engage his audience.

Anthony was the first up for a session titled "Pop and Politics." He titled his talk “Magic Art Reproducer,” after a device to help kids learn to draw. Anthony wove a narrative outward from Warhol’s groundbreaking 1961 "Superman" painting, around various amateur art practices of the era as seen in comic book ads, and into the lives of working-class people. His visuals, which incorporated panels and pages from a variety of sources, helped to engage his audience.

This interview with Anthony is the first of three columns on CAA100. Next up: my discussion with the organizers of the "Pop and Politics" panel about gender issues and "Pop proto-feminisms."

Michael Dooley: How did you become interested in Warhol?

Anthony E. Grudin: At the time, I was working as a teaching assistant at UC Berkeley, and reading and teaching Kant's "Critique of Judgment." I began to feel that Pop tackled Kant's questions in a fascinating way, and that Warhol's approach in particular was worthy of further study. Once I started digging into Warhol's source material – comic books, cheap magazines, tabloids – I found that the world of Warhol's imagery was far more densely complex and calculated than scholars had assumed it to be.

What inspired you to put together "Magic Art Reproducer"?

The essay was inspired by the advertisements for commercial art schools and amateur reproductive technologies – overhead projectors, sound recorders – that I found in Warhol's source texts. But I've been fascinated by the strengths and weaknesses of mass culture and reproductive technologies since I was a kid.

How does Warhol's use of the comic book medium differ from that of Roy Lichtenstein's work during that same era?

Lichtenstein's approach to mass culture offers a really fascinating counterpoint to Warhol's, one that I'm excited to discuss in my upcoming book. In brief, Lichtenstein is constantly emphasizing mass culture's vulgarity, and the differences between his work and the mass cultural motifs it borrows. In 1963, he described his motifs to G. R. Swenson as "things we hate, but which are also powerful in their impingement on us." For Lichtenstein, pop art centers on the sublime challenge of transforming America's very lowest images – mass culture – into its very highest: fine art.

Of course, this transformation takes place in Warhol's work as well, but I don't think it's Warhol's central concern. Instead, Warhol is interested in mass culture's own challenges and frustrations: the ways in which it produces desire and frustration in its audiences, and the ways in which it encourages that audience to participate in the production and reproduction of culture.

How might the class issues raised by Warhol's art be relevant to contemporary politics?

I think these issues are deeply relevant, but in ambivalent ways. On the one hand, Warhol's early paintings provide us with a crucial repository for thinking about working-class-targeted culture and advertising, and the passions and frustrations these images can provoke in their consumers. But on the other hand, Warhol's paintings also turn these passions and frustrations into entertainment. In that sense, the paintings embody an ironic consciousness that is both in love with Superman and Coke and aware of the ridiculousness of this emotion.

And I think that this ironization has deeply sinister consequences; as T. J. Clark has argued, it "produces the conditions for effective, that is, controllable citizenship” because it undermines our ability to take our emotional and political commitments seriously.

[caption id="attachment_278131" align="aligncenter" width="460" caption="Anthony E. Grudin speaking at CAA100's "Pop and Politics" panel. All photos by M. Dooley."] [/caption]

[/caption]

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2012.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares