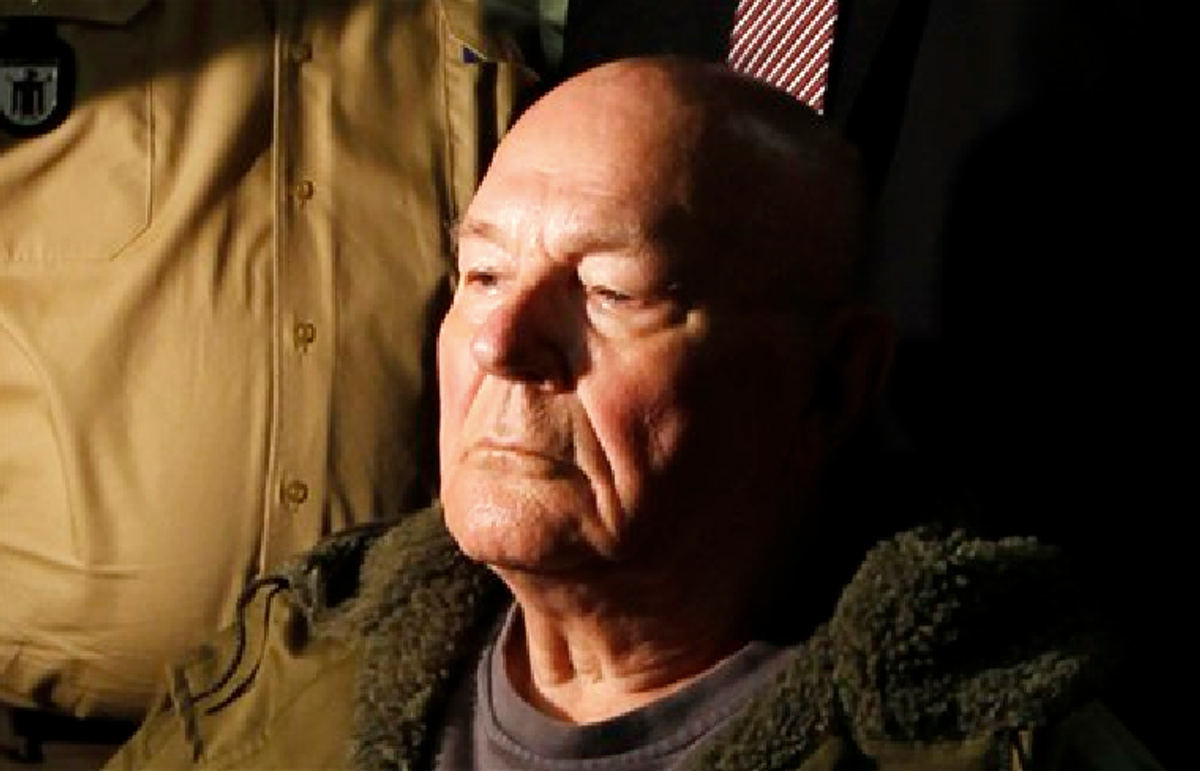

The death of John Demjanjuk in a Bavarian nursing home brings to an end the most convoluted and lengthy case to arise from the crimes of the Holocaust. Demjanjuk’s legal odyssey began in 1977, when American prosecutors filed a motion to strip the Ukrainian-born émigré of his U.S. citizenship. It reached a conclusion of sorts last May, when a German court convicted the 91-year-old defendant of assisting the SS in the murder of 28,060 Jews at Sobibor, a death camp in eastern Poland.

The court’s verdict — Demjanjuk was sentenced to five years imprisonment only to be released pending appeal — aroused controversy, more here than abroad. Rabbi Marvin Hier, head of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles called Demjanjuk’s release “an insult to his victims and the survivors.” Yet the survivors and relatives of victims I spoke to generally expressed satisfaction with the Solomonic verdict. Little was to be gained by jailing the nonagenarian as his appeals wended through the court system. More important was the conviction itself, the fact that a German court had finally managed — nearly seven decades after the fact — to condemn one of the thousands of auxiliaries who served as the foot soldiers of genocide.

Germany rightfully enjoys the reputation as having succeeded in the difficult collective task known as Vergangenhetstbewältigung – confronting the past. While Turkey and Japan continue vehemently to dispute any responsibility for crimes of genocidal sweep, while Spain brings criminal charges against a local magistrate who dares to investigate Franco-era crimes, Germany has emerged as the poster boy for national self-reckoning, the land willing to face down its monstrous past. The casual tourist in Berlin cannot escape the public memorials to atrocity that dot the urban landscape with a mushroom-like plentitude. And when all else fails, German law serves as the muscle of memory, stepping in to prosecute those who would deny the Holocaust.

And yet when it came to bringing Nazi perpetrators to the bar of justice, the German legal system managed to amass a record of impressive failure that stretched back to its founding days. Hans Globke, the jurist who penned the law forcing all Jews to adopt Sarah or Israel as a middle name, enjoyed a stellar postwar career as Konrad Adenauer’s closest advisor. In early 1960, Fritz Bauer, the famous German-Jewish prosecutor, passed intelligence concerning Adolf Eichmann’s Argentine whereabouts to Mossad and not to his own intelligence office out of fears that Germany would botch or sabotage any trial.

More to the point, the vast majority of those who participated in the extermination process never faced criminal charges, and those unlucky few who found themselves indicted were either acquitted outright or received minor punishment. This was largely the consequence of a calamitous holding by postwar German courts that mere service as a concentration camp guard didn’t constitute a crime. Only if one had engaged in some value-added act of violence — such as the unauthorized killing of an inmate — could a former guard be found guilty of a crime. This calculus essentially used Nazi standards of legality in assessing the guilt of camp guards; or to put it another way, postwar German courts condemned only those former functionaries who could have been condemned by the SS’s own tribunals.

In this regard, Demjanjuk’s conviction in Munich represented an important corrective — though admittedly one long in coming. The Munich court accepted a novel theory of criminal responsibility specifically tailored to the realities of genocide. Sobibor, it needs to be recalled, was a pure extermination facility; its sole purpose was the killing of Jews. According to the prosecution, this meant that all Sobibor guards by necessity had been involved in the killing process. That the prosecution couldn’t prove Demjanjuk had beaten to death an inmate or shot another was immaterial; Demjanjuk had to have been an accessory to murder because as a Sobibor guard, that was his job. Once the prosecution was able to prove that Demjanjuk had served at Sobibor — which, despite the persistence of claims to the contrary, it was able to do beyond any reasonable doubt — its case was over. The theory was simple, irresistible in its logic, and yet no court in the Federal Republic had managed to embrace it — that is, before the court in Munich this past May.

It is, of course, regrettable that the German court system took more than a half-century to self-correct. Clearly there is something ironic about a precedent so late it coming that it will furnish no legal legacy. Yet such is the fate of the Demjanjuk case. In the weeks after the conviction, German prosecutors announced their intention to use the novel holding to reopen long-moldering cases, but whether any of these will go to trial remains doubtful. Actuarial realities certainly make this less than likely.

Those inclined to cynicism may also find significance in the fact that this belated self-correction came in a case involving a non-German who served invisibly at the very bottom of the SS’s exterminatory hierarchy. True, Demjanjuk was no Eichmann; he was not even a Nazi, and never would have found service as a death camp guard had the former soldier in the Red Army not been taken as a POW by the Wehrmacht. But what does this prove? The fact that other, more senior functionaries in the exterminatory process lived out their lives unruffled by prosecutors conferred no immunity on an underling in genocide. And without the Demjanjuks of the world, the death camp system could not have functioned.

Few if any rue Demjanjuk’s death. Had his conviction been upheld on appeal, the nonagenarian would have faced imprisonment, a result his lawyers dreaded. And yet the prosecution also feared the appellate process, as the high court might have proved less receptive to its novel theory of responsibility than the trial chamber. In any case, his death brings us one step closer to the day when the Holocaust will pass from the memory of those who lived it and become an artifact of history. And it certainly brings to a close the era of galvanic Nazi atrocity trials that stretches back to Nuremberg. That this era should end not with a Goering or an Eichmann or even a Barbie in the dock is less ironic than it is fitting. The Holocaust was not accomplished through the acts of Nazi statesmen, SS bureaucrats and Gestapo henchmen alone. It was made possible by the Demjanjuks of the world, the thousands of lowly foot soldiers of genocide.

Shares