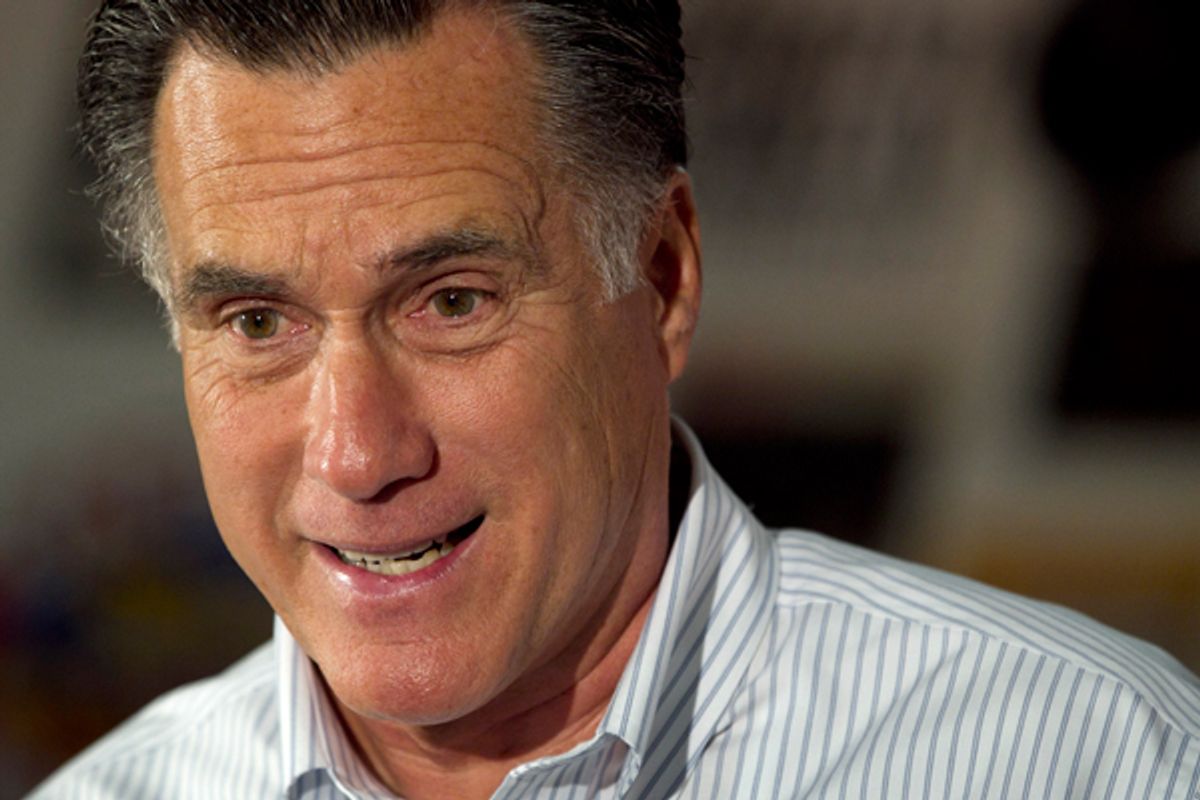

The good news for Mitt Romney is that the big names in conservative politics are starting to acknowledge the overwhelming likelihood that he’ll be the Republican presidential nominee and line up behind him. The bad news is that it’s taken them an excruciatingly long time to reach this point – and even now, their support seems reluctant, qualified, even grudging.

Take Jim DeMint, the South Carolina senator and one of the most influential voices in Tea Party politics. The South Carolina senator provided Romney with a big assist on Thursday, declaring that "I'm not only comfortable with Romney, I'm excited about the possibility of him possibly being our nominee” and hinting that Rick Santorum and Newt Gingrich should reassess their candidacies. What DeMint didn’t do, though: actually endorse Romney. So, officially, he still hasn’t taken sides in the race.

Then there’s Jeb Bush, who offered his support for Romney after Tuesday’s Illinois primary … in a brief prepared statement that was decidedly light on praise for the candidate. There was no splashy rally to make the announcement, no round of television interviews and media appearances to promote it – not even a simple, quick press conference or joint appearance. Just a subdued statement that saluted Romney for winning Illinois, pointed out that many states have already voted, and repeated some boilerplate Republican rhetoric about the economy.

The reluctance of DeMint and Bush to fully embrace Romney even as he’s opened a wide, probably insurmountable delegate lead is a reflection of one of the main reasons he’s struggled so mightily to put his opponents away for good: Even conservative leaders who privately believe Romney is their party’s best option are afraid of being remembered as the one who put him over the top.

This speaks to the peculiar way the GOP has evolved in the Obama era. Essentially, the election of Obama in 2008 prompted conservatives to open a two-front war. One was aimed at Obama, which was nothing new – as the examples of Presidents Clinton, Carter, Johnson, Kennedy and Roosevelt all attest. A Democrat in the White House invariably prompts alarm and hysteria on the right.

The second front, though, was less predictable: an insurrection against the Republican “establishment.” This grew out of the right’s need to explain Obama’s sweeping victory. It couldn’t be that the 2008 election had served as a national repudiation of conservatism, so conservatives retroactively turned on George W. Bush and the Big Government brand of conservatism he’d practiced (a brand of conservatism that, in turn, had grown out of the right’s interpretation of Bill Clinton’s success in the 1990s).

Bush, the story went, had betrayed true conservatism and wrecked the country in the process, creating a political climate that made voters susceptible to Obama and his teleprompter-aided pleas to give the opposition party a chance. The appropriate response, conservatives decided, was to insist on absolute ideological purity from Republicans going forward, and to cleanse the party of those who exhibited Bush-like tendencies on domestic issues.

But their desire to simultaneously oppose everything Obama did forced a redefinition of conservatism, which is how Romney got in trouble. In his ’08 campaign, when he positioned himself as the right’s alternative to John McCain, the universal healthcare law he’d championed in Massachusetts had been an asset for him; he’d used a blueprint drawn up by conservatives in the early 1990s to address a major issue on which Democrats traditionally enjoyed an advantage. But when Obama used Romney’s Massachusetts law as the blueprint for his own national program, conservatives felt compelled to call it socialism and oppose it with all their might.

Thus did Romney become the “moderate” in the Republican presidential race – the candidate who most reflected the brand of Republicanism that Obama-era conservatives had dedicated themselves to extinguishing. Between 2008 and 2012, Romney actually remained consistent on most issues, sticking to the very conservative positions he staked out when he came to the national stage. But his image within the party changed, leading the same conservatives who had sung his praises in ’08 – like DeMint, Rush Limbaugh and even Santorum – to distance themselves from him.

This is why the primary season has been so brutal for Romney. To win over the skeptical conservative base, he needs influential figures on the right to vouch for him. But if they vouch for him, they risk being declared RINOs themselves, establishment sellouts trying to force an impure nominee on the GOP. And they know that any dramatic gesture they make now will be remembered. What if Romney wins the nomination, loses in the fall, and the conservative base concludes they were tricked again – that it’s time to redouble their purity crusade? Or what if Romney wins in the fall and, like George H.W. before him, tries to govern from the middle as president, prompting a GOP civil war. What conservative leader would want to spend the next four years explaining why he or she played such a critical role in elevating that kind of president?

This goes a long way toward explaining the bizarre, protracted GOP primary season. Conservative leaders seem to have concluded that Romney’s opponents would all be poor general election candidates, and that it’s best for the party if Romney wins the nomination. This explains why Santorum and Gingrich have received so few high-profile endorsements, and why officially neutral conservatives have nonetheless weighed in at pivotal moments to kill their momentum. Twice, for instance, Gingrich shot to the top of national polls – once in December and again after the South Carolina primary. In both instances, he faced immediate, brutal attacks from influential conservatives, which sunk his polls numbers and restored Romney to his front-runner’s perch.

What’s been missing, though, has been a parade of high-profile endorsements of Romney from those same conservatives. Bush, for instance, refused to speak up for Romney after Gingrich’s South Carolina win. DeMint has been similarly coy, as have many others on the right. Romney has won the most endorsements of any of the candidates (by far), but what’s most notable about this race is how many key Republicans have opted to remain on the sidelines.

The most logical conclusion to draw from this is that they actually want Romney to be their nominee, and that they’ve wanted him to be their nominee for most, if not all, of this process. But they’re scared to death of having their fingerprints on it.

Shares