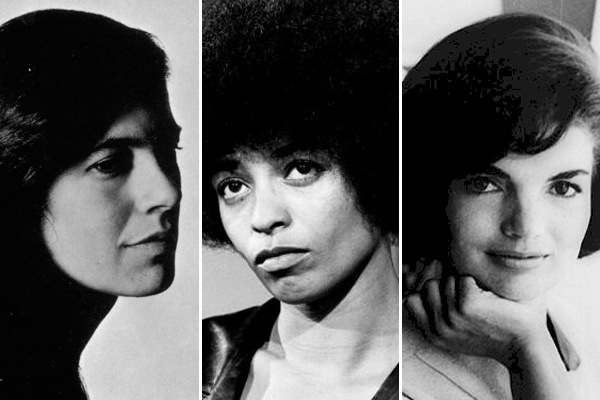

Jacqueline Kennedy, Susan Sontag and Angela Davis are three very different American women who shared one similar rite of passage: a year spent in France during their early adulthood. Alice Kaplan’s superbly perceptive “Dreaming in French: The Paris Years of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, Susan Sontag and Angela Davis” makes a prism out of those visits; the white light of expectation goes in, and a myriad of astonishing colors comes out.

A year abroad is far from a rare experience for American college students these days, but it’s a surprisingly undercontemplated custom; Kaplan — a professor of French at Yale and the author of a memoir and several prize-winning books on French history — singles out a recently-published academic study by Whitney Walton. However, most attempts to understand the transformative visits of young Americans to other countries have come in the form of coming-of-age memoirs and autobiographical first novels. About Paris, above all, American youth has spun extravagantly romantic fantasies of self-discovery, blossoming cosmopolitanism and creative ferment.

Jacqueline Bouvier arrived in 1949, to a Paris that was, literally, black. Its white stone buildings hadn’t been cleaned of street soot since the war. This, like the ration card issued to Bouvier for sugar and coffee, is the sort of detail that sketches an entire mode of life, scrimping and shadowed. Kaplan is a master at delivering such details and at selecting just the right aspect of everyday experience to illuminate an important point she wants to make.

In the section on Sontag, Kaplan notes, “There’s rarely a published account of Parisian intellectual life in the 1950s — French or American — that doesn’t involve hotel rooms.” Sontag, who, unlike Bouvier and Davis, spoke only “elementary” French during her 1957 sojourn to Paris, inhabited a “social world that was essentially American,” a hotel world. For the ambitious young critic, her months in Paris were primarily a period of introspective and erotic exploration; with a husband and child back in America, she submerged herself in an affair with a woman, Harriet Sohmers, who some thought to be the real-life model for the character Jean Seberg played in “Breathless.”

For Bouvier, to the manor born and raised but essentially broke due to the profligacy of her father, France offered a chance to steep herself in the European art and culture she adored. As part of a program run by Smith College, she stayed with a comtesse in the respectable 16th arrondissement, but only because the comtesse (who’d been in the Resistance and done time in a German labor camp), had to take in boarders to make ends meet. The shortage, in this shabby genteel milieu, of both bath tubs and baths, and especially the very basic nature of French toilets, delivered the “most intense” culture shock that Bouvier and her wholesome cohort experienced. The unheated houses of their host families ran a close second. Their Paris was uncomfortable, but replete with the exotic riches of the past.

Davis, on the other hand, arrived in 1963, a fluent French speaker and precocious academic intellectual expected to achieve great things as a philosopher by her mentor at Brandeis, Herbert Marcuse. She’d been imprinted with what Kaplan calls “the mythical power that France held for black Americans” as a realm where a full portion of freedom and dignity, inaccessible in America, could at last be enjoyed. Raised in segregated Birmingham, Ala. — in a neighborhood so plagued by racist bombers it was dubbed “Dynamite Hill” — Davis and her sister had once entered a white shoe store speaking French and pretending to be from Martinique. Instead of being shown to the back entrance for “colored” customers, they were treated “like dignitaries” in the front of the shop. French, for Davis, was the language of liberty, an escape hatch to another, better life.

As Kaplan recounts in an insightful passage on the role of newspapers in the education of American students overseas, Davis had no sooner arrived in France than she picked up a copy of the Herald Tribune to read of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in her hometown. This act of domestic terrorism killed four 14-year-old girls, two of whom were Davis’ friends. Kaplan compares the American and French coverage of the event, all of which Davis must have studied avidly, to illustrate how each society was far more likely to acknowledge the prevalence of racism away from home. In Paris, Davis receive more respectful treatment than she got in the U.S., but all around her she saw Algerians targeted for abuse much like that she’d endured back home.

Kaplan devotes a section of each of the book’s three parts to “The Return,” the story of each woman’s later life in America and the role France and French culture played in it. There’s Jackie Kennedy’s expert negotiation of the politics of the visual, redecorating the White House, and herself, in a manner that satisfied her taste for French design without appearing unpatriotic. (Her husband did complain of “too Frenchy” official dinners, with menus that “nobody could read or understand.”) Sontag became the most visible American intellectual to champion the French “New Novel” to stateside readers. And Davis, when tried in 1970 for conspiring in a courtroom kidnapping and shoot-out in California, became a symbol of the battle for social justice to many French people, tens of thousands of whom marched to protest her imprisonment. French schoolchildren and secretaries sent her letters of support.

Some books are well-written on a sentence-by-sentence basis; you leaf back through the pages to find you’ve underscored choice lines. “Dreaming of French” is the sort of book where you (well, I) draw vertical lines next to entire paragraphs. Kaplan produces some exquisite lines, yes, but she is positively incandescent on the level of thoughts and observations. Of Sontag, she notes the obsessive list-making and sees the outsider, the girl from the provinces schooling herself on the societies she longed to infiltrate: “Throughout her life, she would enter a new world by recording its manners, its important people, creating her own grammar in the form of lists.” The big lectures and rote learning methods of the Sorbonne, she describes as “the part of French education that was as ritualistic as Catholic mass.” In Davis’ childhood efforts to teach herself French, she sees that, “for such a person, a counterlife of dreams and imaginary travel was an absolute necessity.”

Although Davis may have needed it most, all three of these women cherished an imaginary French counterlife as girls. Tracing the effect of an unlived fantasy on a person’s actual life is a delicate operation, but then so is accounting for the influence of that first immersion in a foreign country. Kaplan writes of her subjects that “the deep history of their transformation involved smells and tastes and visions — fleeting sensual experiences not easy to capture in a conventional life story.” An eccentric landlady or the first sampling of couscous can make an indelible impression on a sensibility cast wide open by travel, an impression that can in turn color ideas and feelings for decades to come. No, it’s not easy to capture such things, but Kaplan proves that it can be done.