Now, where were we?

The last edition of Double Bill was way back in March of 2010. A simpler, more innocent time, one filled with such promise. What happened, you probably aren’t asking? Well, I got distracted. In my ongoing role as Sancho Panza to Werner Herzog’s Don Quixote (i.e., his producer), we tilted at not one but two cinematic windmills. The first was "Cave of Forgotten Dreams," along with what I boasted upon its release was the “Feel Bad Movie of 2012 Christmas Holiday Season,” the despairing Death Row documentary “Into the Abyss." If only I had seen “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close" before I opened my big yap.

And that brings us to our first new double bill, our shotgun marriage of two available-on-DVD films. One is new, and just out, and the other, older, somewhat more obscure. Each complements and/or amends and/or purges the viewing experience of the other.

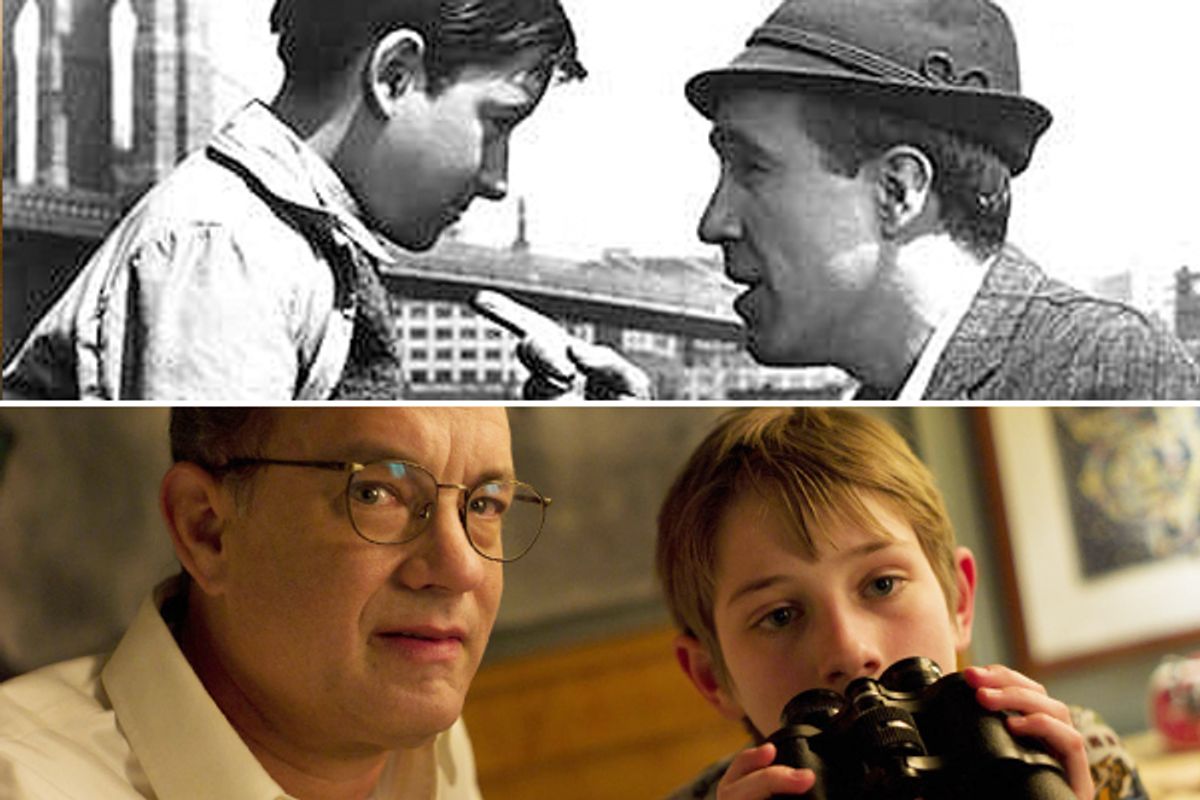

Cases in point? "Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close" and "A Thousand Clowns."

Now what does a high-gloss, Oscar-pandering Important (with a capital “I”) Hollywood version of an Art novel (with a capital “A”) have in common with a mid-'60s scruffy, semi-amateur translation of a now mostly forgotten Broadway hit? Nothing, and everything.

First, “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close.” Based on the postmodernist novel by Jonathan Safran Foer, the film has a few things going against it. First, it is based on one of those books that many people bought because they heard that it was a brilliant, challenging read. But when movie producers who have read books like this -- for all the wrong reasons -- try to adapt them, well, you get adaptations like "Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close," a project that defines the phrase “Eat Your Peas Cinema." To paraphrase that great unsung cinema scholar, “Charlie the Tuna”: these are films that have good taste but don’t taste good.

This project has all the key ingredients for that recipe. Writer, blue-chip adapter of the un-filmable literary masterpiece Eric Roth, best known for the execrable “Forrest Gump," the not-as-execrable but getting there “The Curious Case of Benjamin Button” and the grim “Munich.” Roth may well be the most serious man on the planet, or at least, Planet Hollywood -- a man whose light touch was seemingly amputated around the time he completed work on “Concorde: Airport '79," which is the last movie of his I actually enjoyed. OK. Two words. Sylvia Kristel. Insert Bob Hope growl here.

Back to our Kitsch Kitchen. The director of "Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close," Stephen Daldry, recently brought us such fluff as "The Reader" and "Billy Elliot." Daldry was also the auteur behind the best ever performance by a fake nose, in a film that made me VERY afraid of Virginia Woolf, “The Hours.” And to finish off this recipe of indigestible worthiness, meet the cast. To quote the immortal (I wish. Farewell, Peter Bergman, farewell) Firesign Theatre, “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close" presents the “average stories of working people, as told by rich Hollywood stars.”

Tom Hanks has what appears to be an extended cameo playing the Jewish (!) middle-class jeweler (!!) big West Side Apartment residing (!!!) father of the tormented, genius, 10-year-old offspring of Sandra Bullock. Fortunately, this young genius is played by a gifted amateur, and “Jeopardy”-certified real genius, Thomas Horn. And did I mention across the street lives Death’s most worthy opponent, Max Von Sydow? Who plays a mute Old Country Grandfather? Who manages to steal the movie effortlessly with every droop of his already furrowed brow?

Enough.

I managed to get through all the above without mentioning once the elephant in the room, the third rail of important drama, the Big Gulp of American trauma, designed to blow through this project like cold ashes, 9/11, or, as it is proclaimed here, over and over (and over), “the worst day." It may well have been, and this maudlin film somehow makes that day seem even worse. Charlie Chaplin once said about his craft; “If you are doing something funny, you don’t have to be funny doing it.” My corollary to Chaplin’s law is, “if you are doing something important, you don’t have to be self-important doing it.”

In “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close,” the horror of 9/11 is used to glue together a wholly unrealistic and grating story of un-magical realism, where our aforementioned cast, saddled with endless on-the-nose grim dialogue from Roth, shtick from Hanks, and droops from Von Sydow, perform their oddly passionless play. This is a film about a wholly unbelievable father and son relationship. The streets of New York turn into a wholly implausible combination film set and Disney theme park (with easier parking, it seems). The end result? A wholly unbelievable and mostly incoherent story.

Which is why you might need an emetic after screening this.

Send in “A Thousand Clowns." Unbelievable father and son relationship? Check. The streets of New York turned into a wholly unbelievable film set? Check. A wholly unbelievable apartment location? Check. A wholly unbelievable and mostly incoherent story? Not so fast, there.

Everything that goes wrong in “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close" goes right in this quiet little 1965 masterpiece. It was lost to DVD until last year, when MGM brought it out as part of its “manufacture on demand” release and catch program. Jason Robards gives a career-defining performance as a brilliant man-child raising the equally brilliant “O.W.," or “little bastard” offspring of his AWOL sister. This little bastard is played wondrously by Barry Gordon, and he and Robards’ film is a smart bomb of precision writing, precision performance, and precision casting. It is funny as hell, too.

Much of this brilliant dialogue is played in ‘60s indie style on the streets of New York, every bit as much a set as their cramped New York walk-up. The distance between New York in 1965 and the present day is both great, and extremely close, and one keeps looking for Don Draper to emerge from one of the Manhattan office towers as Murray Burns seeks gainful employment, with the help of his agent brother, Martin Balsam. Balsam, fresh from his backward plunge down the “Psycho” stairs, won an Oscar for, in essence, one riveting monologue. He is the “best possible” foil for Robards, and for once, the Oscar went to the right guy at the right time for the right role.

The narrative could not be more straightforward, as it is taken almost verbatim from a perfectly calibrated three-act play by Herb Gardner. "A Thousand Clowns" premiered in 1962, back when being a comedy hit on Broadway actually meant something. The film version has all that "Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close" lacks. It has structure. It has content. The creation of the film adaptation was left mostly to the original creators. And since we’ve mentioned Mr. Chaplin before, the plot of “Clowns” is as old as “The Kid,” and that is probably not coincidental.

Murray, an intellectual tramp and nonconformist, has raised his found object surrogate son, Nick (aka Rafael Sabatini, aks Insert Dog’s Name), with his core values of hedonism, skepticism and an aggressive lack of materialism. Which of course leads directly to concerned social workers who try and, in the end, succeed in unraveling Murray’s private utopia. Society wants the Kid back. And, it gets him. In a tragic yet wholly logical sequence of events, the child becomes the Man, and the Man becomes a diminished Man. But rather than try to build upon a foundation of postmodernist quicksand, “A Thousand Clowns” had nowhere to go but “up,” where “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close” went down.

In the words of a focus group study (commissioned by Murray’s dual tormentor and savior, the hyper-neurotic kiddie show host “Chuckles The Chimpmunk”), the audiences for “Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close” were “noticeably moved.” “To leave the theatre?” asks Nick, innocently, from the “blue, blue sky” of his faux childhood. And, did I mention “A Thousand Clowns” is funny?

The director of the 1962 play, Fred Coe, also directed the 1965 film, but went as AWOL as Murray’s sister during post-production, leaving writer Herb Gardner alone with his brilliant editor, Ralph Rosenbaum. The story of this film's creation is told in Rosenbaum’s somewhat self-aggrandizing treatise, “When the Shooting Stops, the Cutting Begins.” This book reminds you where his films “The Producers," “Annie Hall” and “A Thousand Clowns” went right, mostly in that their neurotic creators had the good sense to hire Ralph Rosenbaum. But in the case of "A Thousand Clowns," no matter who takes credit, the results continue to amaze.

Realizing that Coe had in essence filmed the play and not much more, Rosenbaum and Gardner spent months “opening up” the visuals, which resulted in a kind of postmodernism that works with, not against, the material. For example, when Murray has to “do lunch” in order to get a social worker-mandated job, we see a series of shock cuts of worker bees on the streets paralleling his descent into conformity, ending with an absolutely incongruous image of meat being thrown to lions. Unlike the twee pastiche of "Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close," this all works, and works perfectly.

Murray manages to captivate and capture one of the social workers, played by a way-too-lovable Barbara Harris. They bicycle through the incandescent streets of lost Manhattan, while he sings in the background, “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby,” with quiet ukulele accompaniment. In this City Of Dreams, every day is Irving R. Feldman’s (the proprietor of Murray’s favorite kosher delicatessen) birthday. This particular vision of Manhattan remains magically realistic, thanks to the quiet craftsmanship, good luck and artistry of its focused creators.

Time stands still on their vision of a best day, where real, earned emotion hard-wires us to a lost era before the twin towers existed, before something hideous emerged from another “blue, blue sky.”

Shares