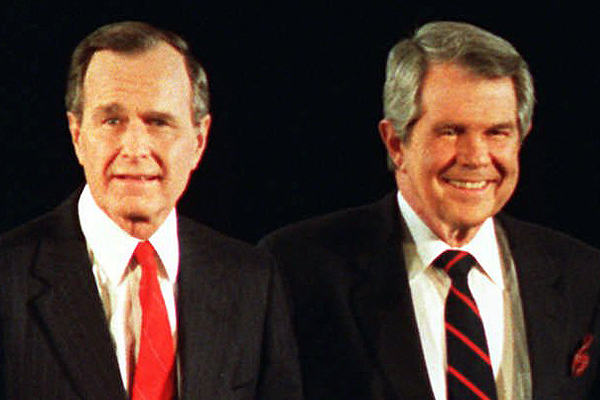

Former President George H.W. Bush is set to endorse Mitt Romney in Houston this afternoon. If this sounds odd, it’s for good reason: Bush already announced his support for Romney back in December, and his wife recorded a robocall for him earlier this month. This time, though, the two men will be together and there will be cameras present, which apparently makes it a news event.

When Bush expressed his preference a few months ago, I wrote about how it actually underscored the main primary season challenge for Romney, who has faced the same basic doubts from conservatives that Bush did in 1988. Like Romney, Bush had once sold himself as a moderate-to-liberal Republican, running to Ronald Reagan’s left in the 1980 GOP primaries, when he endorsed abortion rights and the Equal Rights Amendment and ridiculed Reagan’s supply-side ideas as “voodoo economics.” And like Romney, Bush then spent years frantically trying to make conservatives forget about his past and accept him as one of their own.

Bush managed to navigate his way through the ’88 primaries, and it appears Romney will succeed in doing the same this year. But Romney’s path has been far, far rockier than Bush’s was. To date, he’s lost primaries and caucuses in 13 states, his most recent defeat coming by 22 points in Louisiana last weekend. And while Romney is very likely to break past the 1,144-delegate threshold by the final nominating contest in June, he could also lose 10 more states between now and then. By contrast, Bush suffered a few embarrassing setbacks early in ’88, but quickly put his opponents away by winning 16 of 17 states on Super Tuesday.

It’s worth exploring why Romney has struggled so much more than Bush did, because the biggest single factor — beyond Bush’s status as a sitting vice president — has to do with one specific voting bloc: White evangelical Christians. That they’ve been so resistant to Romney and so capable of dragging out his path to the nomination speaks to the evolution of the GOP since Bush’s days.

The Republican Party that Bush set out to lead in 1988 had been redefined under Reagan as an ideologically conservative party, but born-again and evangelical Christians were still new to it, and still testing and understanding their strength. White evangelicals had swung hard to the GOP in the 1980 general election, motivated by disappointment in Jimmy Carter, who had campaigned as a born-again Christian, and a belief that Reagan would pursue their culturally conservative agenda. They then spent the ’80s building strength at the grassroots level, and saw an opportunity to assert themselves in the race for Reagan’s successor in ’88.

This was a potential problem for Bush, given the doubts about his ideology that had lingered since ’80. As vice president, he declared himself pro-life, moved far to the right on cultural issues, remained fiercely loyal to Reagan, and kept in close contact with Christian right leaders like Jerry Falwell. But Bush, a Connecticut-raised Episcopalian, was still an unnatural fit for the party’s growing core of rural and Southern evangelicals — especially when Pat Robertson entered the race.

In August 1986, more than two years before the general election, Michigan Republicans held a primary to elect delegates to precinct caucuses — the first phase in a 17-month process that would ultimately produce the state’s national convention delegation. Bush, with his massive financial and organizational advantage, filed more than 4,000 delegate candidates. Robertson, with no traditional organization but a formidable grassroots following, did the same. No other candidate even came close. The nervous Bush campaign then spent $750,000 in the run-up to the August primary. Robertson spent about $65,000 — and won.

Similar stories repeated themselves as county and state straw polls around the country in the months ahead. At the Iowa straw poll in September 1987, Robertson engineered a victory with 34 percent of the vote. Bush finished in third place with 23 percent, behind Bob Dole. In the real Iowa contest, the February 8 caucuses, Robertson fared three times better than he had been in pre-caucus polling, earning 25 percent of the vote — good for a startling second place behind Dole, and ahead of Bush.

But that’s about all the magic Robertson could make in ’88. His support was limited to evangelical Christians, who just didn’t have the numbers back then that they do today. In low turnout environments, Robertson’s supporters were able to make noise; he also won caucuses in Washington and Alaska, nearly beat Bush in Maine, and finished second in Minnesota. But when the voting universe was expanded, he flamed out. The other problem for Robertson was that many born-again Republicans ended up giving Bush the benefit of the doubt, partly because he had some evangelical leaders (like Jerry Falwell) willing to vouch for him, and partly because Reagan’s rock-star popularity with the Christian right rubbed off on him. Robertson’s strategy had been to clean up in the South, but Bush ended up crushing him in the region.

Since those days, the influence of white evangelicals in the GOP has only grown. In some states in the South, nearly 80 percent of Republican primary participants now identify themselves as born-again or evangelical Christians. And the numbers have grown elsewhere. In Illinois, long a bastion of moderate Republicanism, more than four in 10 voters in the recent GOP primary were evangelicals. This isn’t enough to dictate the GOP nominee, as Romney’s likely victory shows, but it’s enough for the Christian right to play a vastly more substantial role in the nominating process than it did a generation ago.

Plus, Romney’s struggles with Christian conservatives — he’s yet to win in a state where white evangelicals make up more than 50 percent of the electorate — suggests their long-term involvement in politics may be making them more cynical and less willing to give a suspected apostate the benefit of the doubt. No matter how adamantly Romney insists that he shares their priorities, evangelicals still won’t give him their votes. It’s possible that his Mormon faith has something to do with this. But it’s also possible that evangelicals have just been around the block. They’ve seen candidates like Romney before, gone along with them, and then been disappointed in the result. George H.W. Bush, who reverted to his moderate roots as president, is a prime example. We may be at the point where there’s nothing that a candidate like Romney can say to make the Christian right believe he means it.