When I was 13, my parents drove us 45 minutes from our home on a rural wooded peninsula to a suburban-mall movie theater to see "Desperately Seeking Susan."

I wasn’t eating popcorn: One year after a surgery that removed a portion of my jaw, I could barely chew. This was just one of the small humiliations that had accumulated after I had been diagnosed with terminal thyroid cancer, undergone extensive surgery and testing, survived a recurrence of the cancer, and traded a death sentence for the murkier and far less glamorous reality of a rare genetic disorder. My neck was sliced halfway round, my jaw riddled with holes, and I had been diagnosed with a second, separate and distinct, type of cancer. The treatments had just started to remove the skin cancer ravaging my torso. Over the next three years I would have nearly four hundred biopsies.

I sat with cold hands tucked into each armpit, only half-awake until the movie started, and my perception of the world shifted in a sudden and irreversible way.

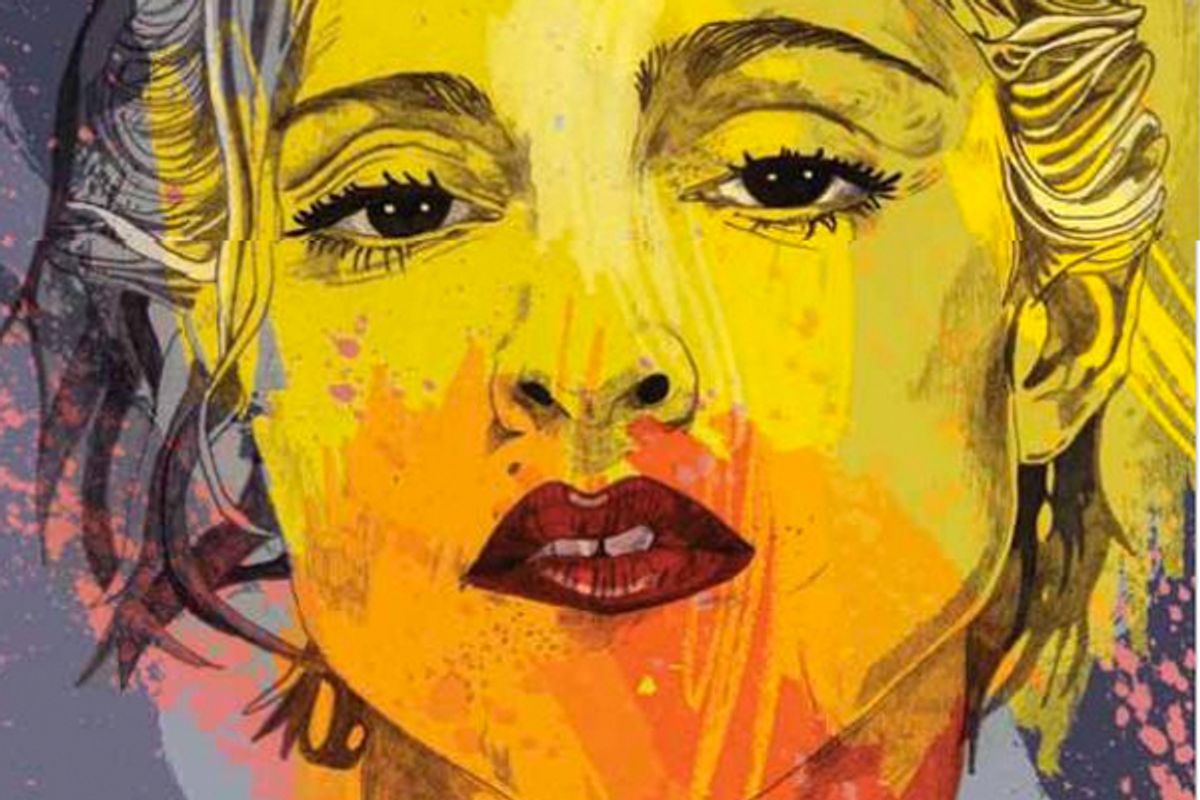

The film offered something that made every hair on my body stand on end: a glimpse of a world that might be out there somewhere — urban, messy, lawless; with cool, caustic boys on scooters, careless girls bedecked in ripped vintage clothes, and enormous empty warehouse apartments.

In the film, Susan was a trickster, a character with no motives, no back story, and no possessions except what she could carry with her or fit into a Port Authority locker. She was all gesture and blithe indifference. She took what she wanted, whether that was a bottle of room-service vodka, the contents of a wallet, a pair of studded boots, or sex on a pinball machine.

Roberta was different: constrained by tradition, rules, responsibilities, life. She had a place in the world, even if she did not like it. And then in an absurd flight of fiction, one knock to the head, a change of wardrobe: Roberta became Susan.

And that wardrobe change seemed to be all she needed. She found a place to stay, a love interest, a job based on her newfound clothes (and confusion). Even after she regained her memory and kept exclaiming, “I’m a housewife from New Jersey!” the truth was subsumed, not just to the cops or the people in her new life, but also to her husband and friends from home.

The movie proposed this radical vision: A costume can change not just perception, but reality.

Precisely when a 13-year-old most wants privacy and autonomy, I had lost all control of my body. Blood, vomit, pus, shit: Everything was discussed, examined, weighed, quantified. Doctors made the major decisions, my parents the minor. I had no choice in even the smallest details; not food, not even bathing. I was not allowed to immerse my skin in water, not allowed to shower. My mother washed my hair in the sink every third day, wrapping fresh scars in plastic to keep them dry and safe.

Other girls might have worried about their appearance, but I didn’t need to bother. I knew that I was ugly—so mutilated, in fact, that I had a permanent gym class waiver to avoid having to disrobe and endure the mockery of my peers.

The surface is indeed superficial, but it matters — it is what you show the world, what you want the world to think and know. And the primary presentation of my essential self, then as now, were the scars. At the start of 1983 I looked garroted, as though I had been hung or strangled or cut in a knife fight. By the end of 1986, I would have hundreds of jagged red slashes and pearly white lumps trailing across my face, chest, shoulders, belly. Others were more obscure, hidden. But even if you couldn’t see them, I could feel them. They throbbed.

"Desperately Seeking Susan" suggested: So what? Don’t try to conform. Wear the costume, be a freak, because if someone is looking at your dress they are not looking at whatever you have hidden underneath.

- - - - - - - - - - -

Just after dawn on a wet gray Saturday morning a few weeks after seeing "Desperately Seeking Susan," my parents dropped me off in a semi-deserted industrial town across the bay from our house. I was early, but not the first in line at the waterbed store, queuing up to buy Madonna concert tickets.

I recognized one of the boys in front of me, Marc. He had a locker near mine in the back hallway of a rural junior high school that resembled a penitentiary. I would never have dared talk to him at school — he was in the ninth grade, while I was a mere eighth grader — but that morning on the sidewalk, we struck up a conversation. He introduced me to his friend Scott, and we whiled away the

hours chatting about music.

That is how it worked back then, back there. The music you listened to made a statement of intent: This is who I am. This is what I believe.

Arguably it was not a wise choice for a fourteen-year-old boy like Marc to declare a sincere love of Madonna. The taunt “fag” was a common and casual insult used to torment my new friends, but not necessarily because of the music they listened to. People our age didn’t have the context. Even then it seemed extraordinary to me that “wannabe” and “poser” were two of the worst insults that could be leveled at a person. How do you define authenticity in your early teens, anywhere, let alone if you live in a failing shipyard town? Should we have worn steel-toed boots and welders’ hardhats?

Madonna tickets secured, I went back to my routine of school, doctors — and drill team.

I had stopped riding the school bus because this kid named Troy tried to set my hair on fire. Lacking a ride for the eight miles home through dense second-growth forests, I was forced to find an approved afterschool club.

Technically, it was less a matter of joining the drill team (I was not issued a uniform, nor did I perform) as being drafted. The young, charismatic drama teacher in charge of the group caught me hiding behind the shrubbery once too often and put my idle hands to use running the tape player as the other girls snapped their necks and hips rhythmically to the latest pop tunes.

These girls were popular, the elite of the school, with a mongrel assortment of athletes as ballast for routines. The captain was Nikki, and her co-captain was Crystal. They, like all the girls on the team, had permed hair, blow-dried and feathered up into quiffs standing several inches above their heads.

My title was “manager,” though I was neither in charge nor even a mascot. I was just there, tolerated, ignored, so long as the teacher was watching. This was the most desirable of all scenarios. If I had any goal at all it was to be unremarkable, invisible, vanished, gone.

Practice was held in the commons, a vast multipurpose room where we ate lunch and attended assemblies, with a three-story atrium and potted plants the size of small cars. I stood at a folding table next to the concrete planters, hitting the buttons on a boom box, flipping the cassette tapes, pausing and starting “Hey Mickey,” “Eye of the Tiger,” “Honky Tonk Woman.”

Whenever the team took a break, I trailed behind them to the nearest restroom, where I watched as they painted their faces with cheap drugstore makeup and curled their hair with the butane curling irons they carried in white fake-leather purses.

I was not trying to fit in with the group (and the attempt would have been useless: Outside of drill team, these girls were among my most vicious tormentors). I was studying them in hopes of creating a reasonable camouflage. Belonging with the drill team without actually having to befriend them was conformity as strategy. If that required tedious long hours listening to adolescent girls’ gossip, fine. If I could parse their mannerisms, clothes, concerns, I might be able to stay alive.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

My new friends from the concert ticket line provided the first real social outlet I had in junior high, and I slowly edged toward the group of people who carried colored folders with pictures of their favorite bands cut out of magazines and taped to the front. These people shared my interest not just in Madonna but in the other things we had seen in stolen moments of the music video show Bombshelter Video, or heard on KJET radio: the Pet Shop Boys, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, Tears for Fears, The Clash, the Eurythmics.

They, like me, hid in the library or art room at breaks. We tried to go to dances and football games to fit in, but never quite looked right, even though we were buying our clothes at the same places as everyone else.

Madonna made popular music (though the popular kids in our school didn’t like it) by trading on her sexual identity, and that fact upset our elders, but we were young: asexual, maybe yearning or experimenting, but unformed. She said, decide for yourself. Our parents did not necessarily agree.

We all existed in a liminal space of possibilities, with a profound lack of agency matched by a desire for control. We sorted ourselves according to bands, liking but not quite understanding what we were listening to. It would take a couple more decades before I figured out what the heck Morrissey was talking about in “Piccadilly Palare.”

- - - - - - - - - - - -

It was time for me to prepare for another round of cancer treatment. Most common foods were rigidly restricted, and I was taken off the medication that controlled my metabolism and kept me alive. Starved of food and hormones, I could barely stay awake during the day. Classes, already fraught with social drama, turned into half-waking nightmares. I can’t even offer anecdotes and stories, just vague semi-delusional moments of horror. You’ve seen the movies: Take it as a given that if my life were scripted by John Hughes, I would be worse off than the nameless neck-brace girl portrayed by Joan Cusack in the movie "Sixteen Candles." I wouldn’t want to read that story, and I certainly did not want to live it.

Outside of class, school was dangerous, even with security cameras in the halls. Violence was common, hazing and bullying were tolerated and often encouraged by staff. The worst of the scenarios, waking or dreaming, too often featured Troy, the kid who tried to set my hair on fire, or Nikki and Crystal, laughing — and the jokes often centered on me, because I could not defend myself. I was too weak to make a fist, and one tap would have shattered my jaw. I learned to be quiet, to watch and wait.

Some people believe there is nobility in suffering, and my family and doctors expected that my peers would respect my vulnerability. The reality is different; profound illness is deviance from the crowd, just like being too smart, too gay, too other. I was different, and different was bad. I was a target of harassment whether I tried to fit in or not. Too sick to succeed, and eventually too sick to care, I kept accounts, clocking each new humiliation.

My hair started to fall out, in strands and then clumps, and no amount of hairspray or sessions with a butane curling iron could hide the fact. One day, I locked myself in the bathroom at home with scissors and my father’s rusty safety razor, hacking and slashing until half the remaining hair was gone.

I was too tired to even flip the tapes as the drill team prepared for the regional championships. Instead, I hid in a restroom the girls did not frequent, sleeping in a toilet stall with my forehead pressed against the cold metal wall.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The day of the concert finally arrived. It was the first concert I had ever attended, the first night of Madonna’s Virgin Tour, and therefore the very first Madonna concert ever. I had a seat in the front row of the balcony, wedged in among my parents, an aunt, and the sole friend left from before the illness, a girl named Christine. The place was a cacophony of sound and activity, though I was drifting, not thinking about much except radioactive isotopes served in a Dixie cup and days spent in cold exam rooms holding perfectly still as enormous machines scanned my body one millimeter at a time.

I was so tired.

The theater filled with rippling waves of enthusiasm, girls in sequins and lace and sawed-off gloves, and I watched as they excitedly took their seats, clapping and hollering for their heroine.

Then something enormously startling happened: The opening act appeared, snarling white rappers from New York City. So foreign, so improbable, so wrong for this audience. They raced around the stage, waving their arms and shouting, and the crowd went calm in confusion, then started shouting back in anger.

This was the first time Seattle met the Beastie Boys, and the city was not amused.

I put my hands over my mouth, laughing so hard I could barely breathe.

The band held the stage a little longer until nearly all the little girls were booing, then they exited with the refrain “Fuck you, Seattle!”

In the interval between the opening act and the concert, the fatigue of the illness and the excitement of the night proved too much.

I put my head down on the railing and fell asleep, missing the rest of the show.

It didn’t matter — I was alive, I was there, and I still own the souvenir T-shirt.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

One weekend afternoon a week or two later, we boarded a yellow school bus for the long drive to the other side of the county for the drill team regional championships. The team was psyched up and ready to prove it in their matching green-and-white polyester tunics and pleated skirts.

The venue was a windowless junior high gymnasium reeking of floor polish and sweat. We watched the clock, watched each other, the various teams whispering behind their hands about minor fashion differences in the sea of feathered bleached hair: a barrette here, a slightly less-than-white sock there.

Then it was time. My team marched out on to the gym floor in formation, hair and smiles perfectly organized, arms held stiffly at their sides, waiting for the music to start.

Standing behind the table next to other managers and the judges, I was supposed to cue their signature song, “Old Time Rock and Roll,” by Bob Seger.

Instead, I hit the button and started the Willie Nelson and Julio Iglesias duet “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before.”

Nikki did not lose her smile as she turned her head and made eye contact with me, hatred burning behind mascara, lip gloss, braces. I stared back, then shrugged, not even pretending to search around for the correct tape.

She signaled and the group dutifully started their routine, not at all in sync with the music, half the girls unable to follow the intricate patterns without the cues of the beat.

After the judges issued a verdict (we lost), the girls huddled together, several crying. I stood against a wall, arms crossed, thinking of the scene in Desperately Seeking Susan when Madonna robs her sleeping date, tips her hat, and walks out of the hotel saying, “It’s been fun.”

Sabotage? Simple exhaustion? I don’t know now, and I didn’t care then. Whether choice or accident, it happened. Motives make no difference, and anyway, those girls were never going to play nice.

- - - - - - - - - -- - -

The fasting, medication, and tests that had made me too tired to watch the concert were leading up to an even more intense cancer treatment, scheduled for spring vacation to avoid interrupting my schooling. But then another unrelated anomaly was discovered, another surgery ordered. The doctors and my parents nodded and whispered and wondered: How to minimize the impact on my education?

The experts wanted to perpetuate this idea of a normal education, normal adolescence, normal life. I was just about ready to accept the goal of remaining alive, maybe, because it seemed to mean so much to my parents. But normal, by then, was too much to ask.

Clutching the skimpy hospital gown tighter around my shivering body, the paper on the examination table crinkling and tearing as I shifted, I said, “I’m not going back. I will burn down the school if you make me.”

Fuck you, Seattle.

The music was never as important as the delivery. The image. The style. Madonna offered a primitive and powerful idea of liberation, like many artists before and since. But her music was popular; it traveled vast distances, penetrated the forest where I lived. And, critically, her music was joyous. During the years when I had many legitimate reasons to feel sad, Madonna made music with an uplifting message: You can dance.

I made some friends, made some enemies, dropped out of school in the eighth grade. Later I went back, and that was probably the point: Wear the costume, and when it stops working, choose another.

There would be other songs, movies, concerts. Madonna embodied the dichotomy: virgin and whore, dutiful and independent, promiscuous and pristine. She did not require a lifetime of devotion — she did not even sustain her own relationships or defined interests all that long. Take what you need, and keep moving.

My life might have been the same without that concert, but it would certainly have had an inferior soundtrack.

The kids I met in line for concert tickets? We all moved away to find the urban, messy lives we were hoping for. Our friendships have unfurled across decades: adolescence, high school, college, emerging adulthood, coming out, marriage, divorce, raising our own children, travels across countries and continents. But though they are the friends who have known me longest, they (like anyone) only see the versions of myself I share and promote.

When I met one of those boys, decades later, in Europe, he asked,

“Why didn’t you tell me I was gay?”

I replied, “It was none of my business.”

I asked if he knew I was in treatment for two different kinds of cancer in the ’80s. He was shocked. “No!”

The disease wasn’t what I wanted to show, and therefore, he didn’t see it.

- - - - - - - - - -

Last year, I visited my hometown. I was sitting in a coffee shop talking to my mother about plans for the future. The question was where to move next: I was having trouble deciding. This was a conversation I’d had with dozens of friends and colleagues all over the world.

London, Paris, Berlin — which should I choose? I said the words, then started to laugh wildly at the perversity of having the discussion in that place. I was still laughing when I realized that someone at the next table was listening.

I turned to look. It was Nikki, with shorter but still-dyed-blonde hair, jogging clothes instead of the team uniform, and she was staring at me with revulsion. Just like the day I caused the squad to lose at regionals.

I stared back for a sustained moment, and it was like we were once again wielding colored folders declaring our cultural affiliations.

Did Nikki recognize me, or was she just annoyed to have her morning interrupted by the loud chatter of an interloper, someone so obviously from out of town? I’ve lost my rural accent. My clothes, the things I carry with me, communicate that I do not live in the Northwest, or anywhere in the United States. I can’t help it — that is just true.

I’m still the raggedy girl in spectacles, the drill team manager who hits the wrong buttons, dreaming of elsewhere. Nikki is forever the carefully groomed captain, the boss of her small syncopated corner of the world. Maybe there were no possibilities after all: Maybe we were simply what we were, and would always remain.

And maybe that is okay.

Excerpted with permission from "Madonna & Me: Women Writers on the Queen of Pop." Copyright Bee Lavender, courtesy of Soft Skull Press.

Shares