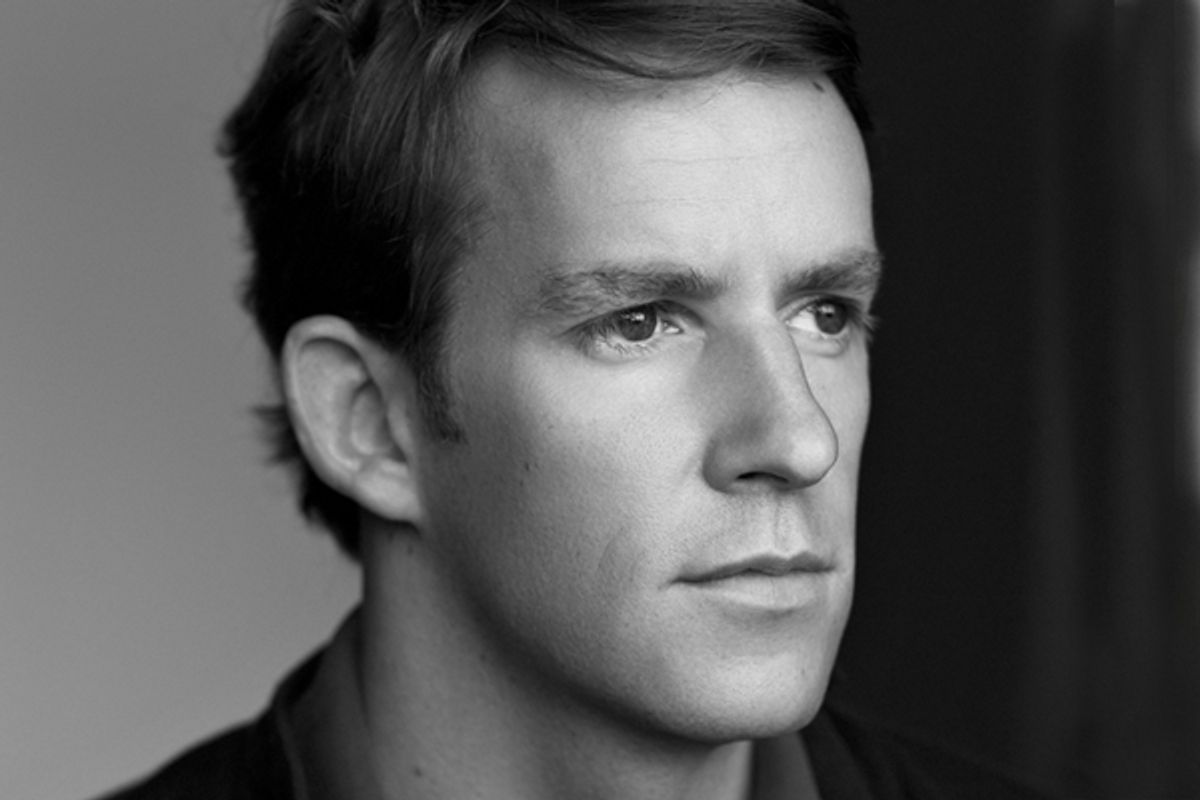

Two years ago, Bill Clegg's first memoir dropped like a bombshell on the New York media world. "Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man" chronicled the handsome and hugely successful book agent's descent into a harrowing crack addiction that cost him his career, his boyfriend and his savings -- and left him broke and in rehab. In one harrowing part of the book (excerpted in New York magazine) Clegg decides to blow off a first-class flight to Berlin after a week without sleep for a crack binge and sex with the cabbie driving him to his airport hotel. Staring at his pile of drugs, he wrote, "I wonder if somewhere in that pile is the crumb that will bring on a heart attack or stroke or seizure. The cardiac event that will deliver all this to an abrupt and welcome halt."

In the years since the events of the first book, Clegg has rebuilt his career as an agent and become one of the best-known faces of addiction recovery. (He is also the rumored muse for "Left-handed," a recent book of poetry by Jonathan Galassi, and the supposed inspiration for one of the lead characters in "Keep the Lights On," Ira Sachs' well-reviewed new film about a troubled gay relationship).

Now Clegg has written a follow-up, "Ninety Days," a tumultuous chronicle of his early sobriety. The book begins with Clegg's release from rehab and follows him as he struggles to keep clean for 90 days, a milestone for those in recovery. Over the following weeks, he tries to rebuild his shattered life -- befriending other recovering addicts, searching for a new apartment and shuttling from meeting to meeting -- but before long, he is once again drinking, smoking crack and having anonymous drug-fueled sex. Thus begins a dramatic series of relapses.

The book, which is written in straightforward, readable prose, is an often-vivid testament to the difficulties of overcoming addiction and the value of companionship. Despite occasional moments of cattiness (Clegg can be ungenerous in his description of other meeting attendees), Clegg comes across as a deeply troubled but a perceptive and sympathetic man, learning lessons about addiction in some very difficult ways.

Salon spoke to Clegg over the phone from Manhattan about the fallout from his first book, the unique appeal of recovery memoirs and why he won't be writing another book.

It’s been a long time since the events of this book happened, and now you're doing interviews and publicity about them. Does it feel strange to be rehashing all this stuff?

I wouldn’t say it’s strange, because one of the ways I’ve stayed sober is to stay very close to the things that happened, both when I was using and also in early recovery. I can’t talk enough about those early days of getting sober, because it’s the things I did and the lessons I learned -- and the things suggested to me in those early days -- that keep me sober today. The more comfortable I get and the more I forget it, the more vulnerable I am to relapse. And it’s pretty simple. Those experiences in those first 90 days are ones I never want to get away from and never want to forget.

Your first book was about your descent into drug addiction and alcoholism. This book is about your recovery. Why did you write it?

It came from a sense of not being finished when I completed the writing of “Portrait of an Addict.” During the three years it took to write that, I felt tethered to this live thing that needed my care and attention. I had this expectation that when I was done I would feel severed from that and I didn’t. So I just kind of didn’t stop writing. But I don’t feel connected to it, or any writing, at this point. I feel completely done.

In what sense?

Finishing this book, the process definitely stopped. I was reading the audio book a couple weeks ago and I hadn’t seen the text in a while. Reading from beginning to end, I almost couldn’t identify with the person who wrote the book. I identified with the person who lived the experiences, but I couldn’t really identify with somebody who would sit for six hours at a time and see that [book] to completion. I just don’t have it in me right now; it’s beyond my imagination that I’d be able to write anything longer than an email. Which is a relief, let me tell you. These books just sort of bullied their way into existence. I have a pretty busy day job as an agent, so I’m kind of amazed that they exist, these things.

What do you think is the overall message of this book?

I thought that once I got out of rehab that if I just stayed away from drugs and alcohol and followed a few simple suggestions there would be a clean narrative of getting sober, that there’d be a before and after that would be clearly defined. And that process for me was a lot messier than that. So if there’s a message in there, it’s that the only way that, in my experience, I’ve gotten sober and seen other people get sober is by asking for help and getting involved deeply in a community of addicts and alcoholics in recovery.

The first book was such a huge success. How did you deal with the sudden fame that came with it? The book included some pretty shocking scenes.

I guess I dealt with that in the same way I dealt with every difficult or wonderful thing, which is one day at a time. If I step back and regard any aspect of my life, whether that be my relationship with my family, or my job, or that publication, or this one, I will probably get overwhelmed and driven to my knees in exhaustion and despair. I was busy at that time doing my job so I just did everything that I always do but maybe with a little bit more desperation. I didn’t stop and look around and try and make meaning of any of it. I just kind of showed up to what I needed to show up to -- whether it was an interview or working on the copy-edited manuscripts or whatever -- and then moved on to the things that crowd my life.

Do you think your disclosures from “Portrait of an Addict” have changed the way people interact with you?

Because my collapse and the revelations of my alcoholism and drug addiction were so known to people in the book publishing world, it sort of mediated or affected every interaction I had professionally when I came back to work, whether that was with prospective new clients or colleagues. I think because that history was informing so many of my interactions and relationships, I got used to it as a kind of third person in the room. In terms of people outside the sphere of book publishing, it was challenging. I’m a self-conscious person by nature, and there were certainly uncomfortable moments.

Is there one big moment is "Ninety Days" that stands out to you as being particularly meaningful?

When I look back and try and locate some moment where a great shift occurred, it was the feeling [at one point during the recovery period covered in the book] when I was walking toward a place where I did drugs all the time. I was walking towards the door and thought of Polly (this woman I got sober with who is still very close to me) who was not sober at the time. She was, at that point in her recovery, pretty dire -- like life or death. I felt like if I went in and got high and went down that rabbit hole, she might show up to a meeting and find out that I had relapsed and that that would keep her out of there.

My involvement in her recovery and connection to her was the thing that stopped me from walking through that door. Somehow the pull of my feeling of usefulness and responsibility to Polly was greater than my desire to use. That was the first time anything stood between me and a drink or a drug. And I turned around and walked away. Very soon after that, the obsession to use and to drink lifted, which was something that hadn’t happened in all of the time that I had tried to get sober.

To me that reminds me how important it is to stay connected to other people in recovery. To me recovery is sort of moving from the first-person singular to the first-person plural. For me as an addict, I can get very consumed with my own anxieties and worries and struggles and ambitions. And if I get too wrapped up in those thing and lift away from my usefulness to other addicts, I’m most vulnerable to relapsing.

In the book, you enter a lot of spaces in which people are meant to be anonymous. There must have been tension between describing the people and wanting to preserve their privacy.

I felt very comfortable talking about my experience getting sober without naming the program of recovery that I’m involved in. And in the instances where there are people in the program that I got sober with and who are still in my life, I spoke to them about the fact that I was going to describe our experience and went to lengths to protect their anonymity and their privacy and followed their lead in terms of what they were comfortable with and what they weren’t. The main point is to transcribe my struggle to get a toehold in sobriety and maintain it. I didn’t feel that the focus of the book is on anyone else’s recovery necessarily, outside a handful of relationships that I had and still have.

One person in the book about whom this question arises is the character of Asa, whom you describe extensively as he helps you during your early sobriety. I’m assuming you weren’t able to get his permission to write about him.

I didn’t think so. He was, he made it clear at a certain point that he didn’t want to have any contact with me because he was no longer sober. But I’m very happy to report that he’s come back into recovery and is sober. He knows that he is in the book, and that he is well masked. I went to great lengths to protect his privacy.

You’ve been the rumored “muse” of a few projects that have gotten coverage in the media in the last few months. How does it feel to be the subject of that kind of attention?

I don’t really have anything to say about that.

One of those projects, the film “Keep the Lights On,” recently got a distribution deal. Did you have any participation in that?

I guess I can’t really speak to any books or films that any other people wrote that I may or may not be connected to by speculation in magazines and elsewhere. It’s not my place.

Fair enough. Going back to your book, the most famous recovery memoir in recent years is the controversial “A Million Little Pieces,” by James Frey, which you allude to in the book. Did other recovery memoirs affect your way of thinking about this book?

You know I haven’t read, probably very consciously, other books of addicts and recovery -- but particularly in the last seven years, when I’ve been involved in working on these two books. People I got sober with would use this phrase, “compare and despair.” I probably internalized that while getting sober and set out not to read other books about addiction and recovery when I was writing these. I would probably think they were better writers than me, or be affected by it so I just felt like in the writing of these books, I just had to follow my own instincts.

What do you think is the appeal of the addiction and recovery memoir for readers?

I think there are a lot of alcoholics and addicts in this world. And they touch a lot of people. It’s a disease that cuts through all class and age and race, and affects many, many people. I certainly myself felt very lost when I was first trying to get sober, and other people in my life felt incredibly lost. Both experiences are very isolating, so when reading an account of somebody getting sober -- or in the case of David Sheff’s book “Beautiful Boy,” reading an account of a parent whose kid is an addict -- I think identification is a powerful thing. It makes the struggle feel less singular, and it shows at least one particular path which one may choose to take or not take in any of those circumstances, whether you’re an addict yourself, or the father of an addict, or the daughter or son. I think people look to books to find answers, separate from addiction and alcoholism, they look to stories to illuminate their lives more clearly, to more clearly find their way.

I think there’s also the appeal of witnessing someone’s downfall and redemption.

Perhaps. People tend to make mistakes, and the reading of how someone may prevail against those mistakes may be encouraging to some people. If it is, that’s one use of those books.

Shares