Not long ago, presidential candidate Rick Santorum complained that he was discriminated against at the University of Pennsylvania because he was more conservative than his professors. I don’t know what his situation was. But I found that standing up for my faith was a positive experience — once I learned how to do it without being a jerk.

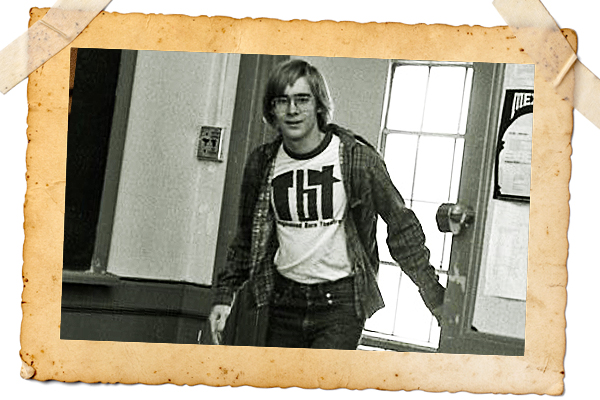

When I entered college, I was a bright-eyed evangelical, ready to take on the world for Jesus. Just getting to college was something of a triumph for me. To say I was a mediocre high school student would insult all the other mediocre students out there. I was on my way to dropping out when I had a religious conversion experience. The most important part of that epiphany was a new focus to my life. Once, I was just drifting. Now, I searched for meaning.

The most meaningful thing I could think to do was to tell the rest of the world how good Jesus was for me, and get them to believe as I did. So I went to the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, got involved in the campus Christian fellowship group, joined a small group Bible study, and took my first religion class — Old Testament history.

It was my first brush with academic religion — well, more like a full-scale collision. I believed the Bible was divinely inspired literal truth and a practical guide for living. My professor believed it was a historical document — an inaccurate historical document — and that if there were any truth in the Scriptures, it existed only between the lines.

My grades remained decent because I read every assigned text and did well on the tests. But at the end of the semester I did an extra-credit project to “prove” my theology was superior to his. He tried to dissuade me, but I went for it anyway.

What resulted was perhaps the first time in recorded academic history when an extra-credit project actually lowered an overall grade. His comment to me was something along the lines of, “If this is what you think an academic paper is supposed to look like, you have clearly not learned anything in this class.”

At first I was angry. I was sure he lowered my grade because he was embarrassed to be proved wrong. I wore my poor marks in that class as a badge of honor, a sign that I was standing up for God, and being persecuted for it. But then I encountered a Bible verse I had never really understood before. It was from the Book of Peter (I Peter 3:15). “Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect.”

My paper was anything but gentle and respectful. I was arrogant and rude. I never even considered the possibility that my professors might know more about the Bible than I did. And while his approach to the Bible might not have been right, I realized something profound at that moment: Neither was mine.

I changed after that class. In the four years I spent at UNCC, I didn’t stop standing up for my faith. I still challenged professors, wrote letters to the school newspaper, gave talks to student groups, and generally tried to sneak in issues of faith wherever I could. But I tried to do it with gentleness and respect. I tried to give reasons for my hope.

And I was often surprised how well my attempts were received, even by professors I viewed as adversaries. A vocal atheist who taught my philosophy class once made the off-handed comment that Paul was a real SOB for saying “If your hand offends you, cut it off.”

I raised my hand. “Sir,” I said, a little hesitantly, “I think Jesus said that.”

He slapped this away. “No, it was Paul.”

I tried to remind myself: Gentleness. Respect. “I think Jesus said it, in the Gospel of Matthew.”

“I’m pretty sure it was Paul.” He did not sound so confident now.

“I think Jesus said it in the Sermon on the Mount. Matthew 5, probably around verses 29 and 30.” OK, so I was approaching the borders of arrogance, but I also knew that my professor was just plain wrong.

“Maybe it was Jesus,” he said.

After class, as I was leaving, he called me over. I was already wondering if I needed to drop the class now that I was on his hit list. I figured he would say something like, “Don’t ever embarrass me like that again. ”

Instead, he said, “You have something that is disappearing in this country. ” His voice was wistful. “If I mention the parable of the prodigal son, or say ‘Am I my brother’s keeper,’ you know what that means. No one else in the class does. We used to have a common language, but that is a thing of the past.”

The professor and I became friends, and I took several of his classes. I never converted him, nor did he lodge loose my faith, but we had a mutual respect. We often sparred in class, and he usually won, but I came away smarter and sharper for it.

I realized that if I was going to stand up for my faith, I had to read more, and do more work than other people in the class. Jesus did not need any ill-informed half-wits trying to defend him. Standing up for Jesus stupidly made Jesus look stupid.

In English class, we were studying existential literature. Now for me, at the time, the existentialists were The Enemy. But that meant I had to read the text even more diligently than my fellow students, and that I had to know the background and philosophy of the author better than even the professor.

It was a depressing class. As we talked about the short story (Hemingway’s “The Capital of the World”) I could feel a darkness settling. We were all disheartened. But I pointed out that while Hemingway saw life as a futile quest for glory, he also sought glory and his writing was glorious — if sometimes a tad bleak. His life belied his philosophy, I said.

I didn’t mention Jesus or God or the Bible. Instead I spoke about “the hope that I had.” I don’t know if I was right about Hemingway that day, but I know spirits lifted. A few of the class members even thanked me for my remarks.

In my senior year, a traveling evangelist came to campus and gave a fire-and-brimstone harangue in the quad. During a break I suggested he might want to use more sugar than vinegar. “You are not bringing anyone to Jesus,” I told him. “You are just making Christianity look mean and insulting.”

He turned away from me, and started up his diatribe again, but this time he aimed his bile at me. “Mickey Mouse Christians like this man water down our faith, and deny our Savior. He is neither hot nor cold, and our Lord will vomit him out his mouth,” he said, quoting a verse in Revelation. But the real shock came when the group who assembled to heckle the preacher now laid into him with a vengeance — because he had attacked me. People who had previously mocked my beliefs were now standing up for me, and eventually they drove off the preacher. A few weeks later I was offered a job as news editor for our campus paper. “You’ve written so much for us already,” they said, referring to my numerous letters to the editor on faith, “we figured you should probably be on staff.”

When I hear complaints that Christians are being persecuted on college campuses, I want to laugh. Sure there are some nasty people who want to wipe out religion, but most “persecution” experienced by Christians is the result of their ham-handedness in trying to foist their faith on others. They may find themselves ridiculed, but only because what they are doing just looks ridiculous to many people. Standing up for my beliefs never required me to be obnoxious, or an idiot (although I am sure there times when I was both). I got into some pretty heated arguments, but the people I clashed with often became friends.

The important lesson on faith is not “Shut up and sit down.” It is, “Speak up, but do it with respect. And be able to back it up!” Fighting for my faith was a learning process. When I thought I knew it all, I was just a blowhard. But when I listened to my detractors — and respected them — I gained their respect, too.