A while back, Politico’s Dylan Byers noted the Romney campaign’s habit of refusing to cooperate with major news organizations pursuing stories about the candidate. The idea wasn’t that Romney was ignoring the press completely -- just that he and his team were being unusually selective when it came to dealing with reporters.

“On some articles,” Romney’s spokeswoman told Byers, “we offer comment. On others, we don’t."

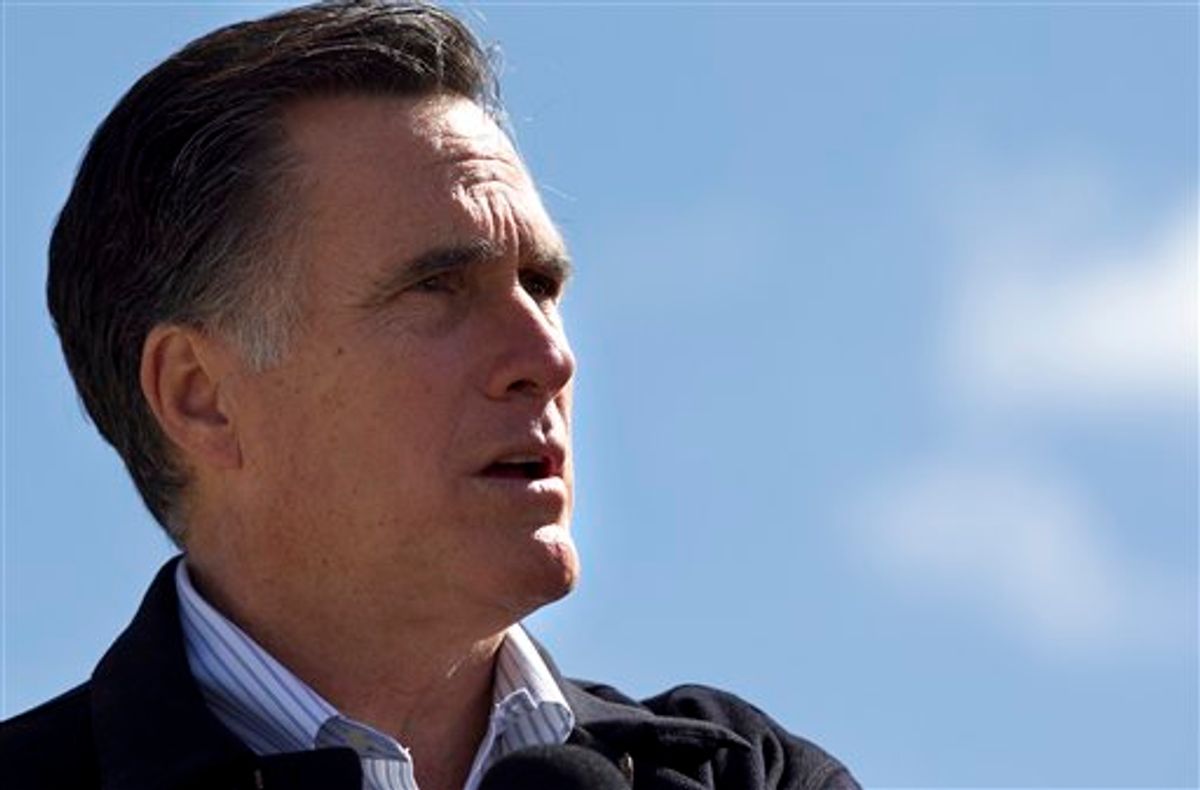

So it seems noteworthy that the candidate himself agreed to an interview with the New York Times for a story that ran on the front page of Sunday’s paper about his relationship with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The two men, it turns out, were actually co-workers at Boston Consulting Group for a brief period 36 years ago, and have kept in touch through the years, particularly since Romney won the governorship of Massachusetts in 2002 and moved to the national stage.

The piece is full of details about their interactions, from meetings at BCG that left Romney feeling envious of Netanyahu’s “strong personality and distinct point of view” to a personal briefing on Iran by the Israeli leader just before this year’s Super Tuesday primaries. “We can almost speak in shorthand,” Romney told the Times.

There are those who will say the relationship raises the question of whether Romney, who has hewed to the Netanyahu line on Iran and other Middle East issues throughout the campaign, might as president be excessively deferential to his old colleague. But this misses the point, because even if there was no long-standing personal relationship between them, Romney – both as a candidate and as president – would have a clear political incentive to align himself with Netanyahu: It’s what the base of his party wants and expects its leaders to do.

Maybe this has something to do with why Romney chose to cooperate with the story. Consider his political predicament right now. He’s almost certainly going to be the Republican nominee, but a major component of the party’s base – white evangelical Christians – is still refusing to join the bandwagon. This has stretched out the nominating process and resulted in some very embarrassing nights for Romney. If evangelical resistance doesn’t dissipate soon, he could continue to suffer primary losses through May and June, even as he moves inexorably toward the 1,144-delegate mark.

There are two dominant theories about why the Christian right isn’t wild about Romney. One holds that conservative evangelicals tend to care the most about cultural topics like abortion and homosexuality and are thus more likely to be bothered by the liberal positions Romney took back in his Massachusetts days, and skeptical of his conversion story. The other holds that they don’t want to vote for a Mormon.

But Israel is also a huge issue for evangelical Republicans, who share Netanyahu’s hawkish, settler-friendly views and ardently support him in his battles with the Obama administration. Playing up a decades-old relationship with him represents a rare opportunity for Romney to demonstrate natural common ground with skeptical evangelicals.

It’s also another chance to ingratiate himself with one of the Republican Party’s top fundraisers, Sheldon Adelson, the casino magnate who’s poured more than $10 million into Newt Gingrich’s political efforts. Adelson, a Netanyahu ally whose political activity is driven by his views on Israel, has indicated that he’ll back Romney against Obama, but continues to take shots at the former Massachusetts governor. This is one of the new realities of the super PAC era: It’s conceivable that a candidate like Romney could be aiming his public actions at an audience of just one billionaire.

Within the GOP, in fact, there’s really no downside for Romney in being so closely associated with Netanyahu. This reflects the party’s evolution over the past generation or two. Evangelicals didn’t begin mobilizing for electoral politics until the late 1970s, but now make up nearly half of the GOP. And for many non-evangelicals, fear of Islamic extremism now serves as the motivating force that anti-Communism once did. To these Republicans, a right-wing Israeli prime minister like Netanyahu is a popular leader.

So ultimately, Romney’s alliance with Netanyahu tells us more about his party than about him. It wasn’t long ago that Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush made sure to keep distance between their governments and Israel’s. But in today’s GOP, there’s no such thing as too close.

Shares