The Bush administration hasn’t heard the last from Philip Zelikow. After the rediscovery last week of his long lost 2006 anti-torture memo, Zelikow, a former State Department official, has written arguably the most damning article yet about U.S. government’s interrogation policies from 2001 to 2009. The article, called “Codes of Conduct for a Twilight War,” will be released in a forthcoming issue of the Houston Law Journal, and was obtained exclusively by Salon. Says Zelikow in an email: “I'm not aware of other accounts that combine historical, policy and legal approaches to” the subject of the Bush administration’s interrogation methods.

Based on published histories and his firsthand observations, and adapted from a lecture delivered in November, the article calls the administration’s rationale for its use of torture — which he nonetheless insists only on calling “extreme interrogation” and “coercive methods” — “radical,” “an amazing contention,” “untenable and extreme,” “unsustainable,” “an unprecedented program of coolly calculated dehumanizing abuse and physical torment,” and, finally, simply a “mistake.” He concludes: “This was a collective failure of American public leadership, in which a number of officials and members of Congress (and staffers) of both parties played a part, endorsing a CIA program of physical coercion without any precedent in U.S. history.” In fact, “The only defense against criminal prosecution would be that officials acted in good faith reliance on the advice of their government lawyers.”

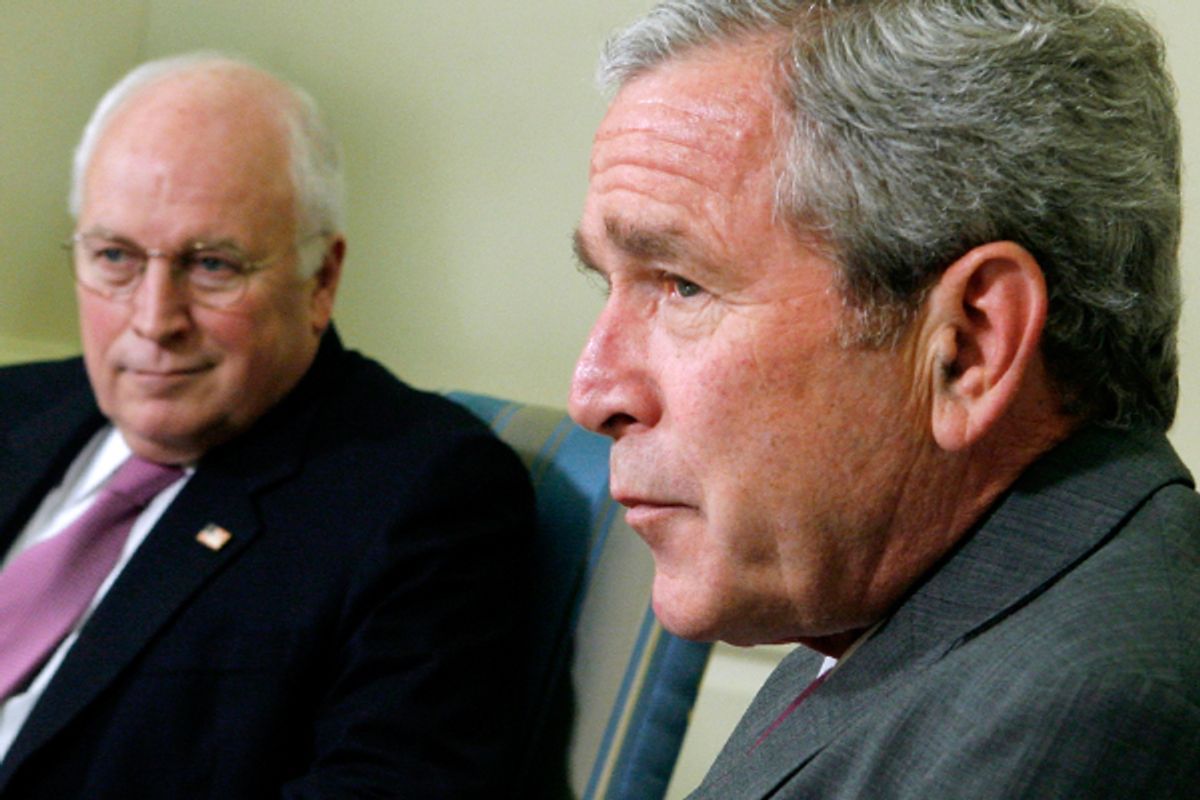

Part of what makes Zelikow’s analysis so damning and definitive is its judiciousness. The article is deeply empathetic of the uniquely fearful situation under which the Bush administration was initially operating. Zelikow calls the Sept. 11 attacks a “collective trauma” and a “shoc[k] to mass beliefs.” He notes that Bush and others spent time in burn units, morgues and with survivors of the attacks. One traumatic experienced often overlooked — overlooked because it appeared in Stephen Hayes’ stenographic biography of Dick Cheney — was that the vice-president’s daughter was (falsely, it turns out) told that her house with her children in it had tested positive for anthrax. Similarly, Cheney and National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice were told that they and others had been exposed to an extremely lethal toxin in a particular area of the White House — and might soon die as a result. “The alarms did not stop and they too were not abstract … The pressure on Bush and his senior advisers was so direct because so much of the response had to be invented and improvised,” the article reads.

An additional factor in the power of the article is Zelikow’s credibility and history. Before entering government, he was a civil rights lawyer in Texas battling the Ku Klux Klan and then a highly esteemed Harvard historian specializing in U.S. foreign policy — he co-authored one book with Rice. He then served on the National Security Council under President George H.W. Bush and directed the 9/11 Commission before becoming counselor to Rice at the State Department from 2005 to 2007. He currently volunteers part-time on the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board under President Obama.

Such bipartisan, establishment credentials render the breakdown and conclusion of this article all the more damning. He believes that what should have been a political and moral question — should the United States torture captives? — became strictly a legal matter left up to government lawyers, few of whom had any experience with these issues, and who had to take the necessity of extreme measures as a given. “These lawyers then became secular priests, granting absolution to the supplicant policymakers,” Zelikow writes.

The problems began when the Office of the Vice President and the CIA took central roles in policymaking. Cheney felt himself above the rest of the National Security Council, bypassing Rice and other traditional channels of national security policymaking. Ad-hoc decision-making and improvisation became “a habit of thought,” which seemed initially to pay off in the security of the nation, as well as in Bush’s political standing and self-confidence.

With Cheney and CIA head George Tenet “the key entrepreneurs in setting codes of conduct for the War on Terror,” it was essentially left to their obsequious lawyers to decide, in secret, on the interrogation methods America should employ. Bush even told the Senate’s Intelligence Committee chairman that “the vice president should be your point of contact … [He] has the portfolio for intelligence activities.” Decisions were made to jettison international treaties. By December 2001, the CIA was already interested in reverse-engineering methods “heretofore used only to treat Americans to resist enemy torture.” When a senior al-Qaida member was captured in March 2002, the prototype for the administration’s torture policies was already developed. “So, for the first time in American history, leaders of the U.S. government carefully devised ways and means to torment enemy captives.”

Zelikow notes that “None of the policy or moral issues connected with these choices appear to have been analyzed in any noticeable way.” Perhaps worst of all, no serious consideration was given to weighing the costs of benefits of the torture program, with reference to relevant historical precedents and/or examinations of the respective French, British and Israeli experiences in dealing with captured terrorists. “Bush and Rice should have insisted on this,” Zelikow writes.

The 52-page article observes the successes of Obama’s counterterrorism policies after repudiating the use of torture. On the basis of the empirical evidence then, “[t]here is no evident correlations between intelligence success and the available of extreme interrogation methods,” no matter what Bush and Cheney claim. Finally, “The program’s costs — which include the high-level effort expended in order to establish, maintain, and defense the program — appear on the evidence so far to have well outweighed any unique value the program might have had as a method of counterterrorism intelligence collection.” This is apart from the damage to America’s international standing and corrosion of its traditional values.

Zelikow concludes his analysis by arguing that, although the Obama administration has the right to wage war and use extralegal methods to defeat al-Qaida, its claim of that authority to defeat “associated forces” is unwarranted. “The U.S. government should publish and explain any overarching policy and legal documents that guide and confine the conduct of deadly operation against its foreign enemies … the executive branch of the U.S. government has a duty to articulate the scope of its warfare to the Congress and the public.” The Bush administration’s unprecedented elevation of torture to national policy may be history, but the job to get U.S. foreign policy in line with its constitutional and moral obligations is far from over.

Shares