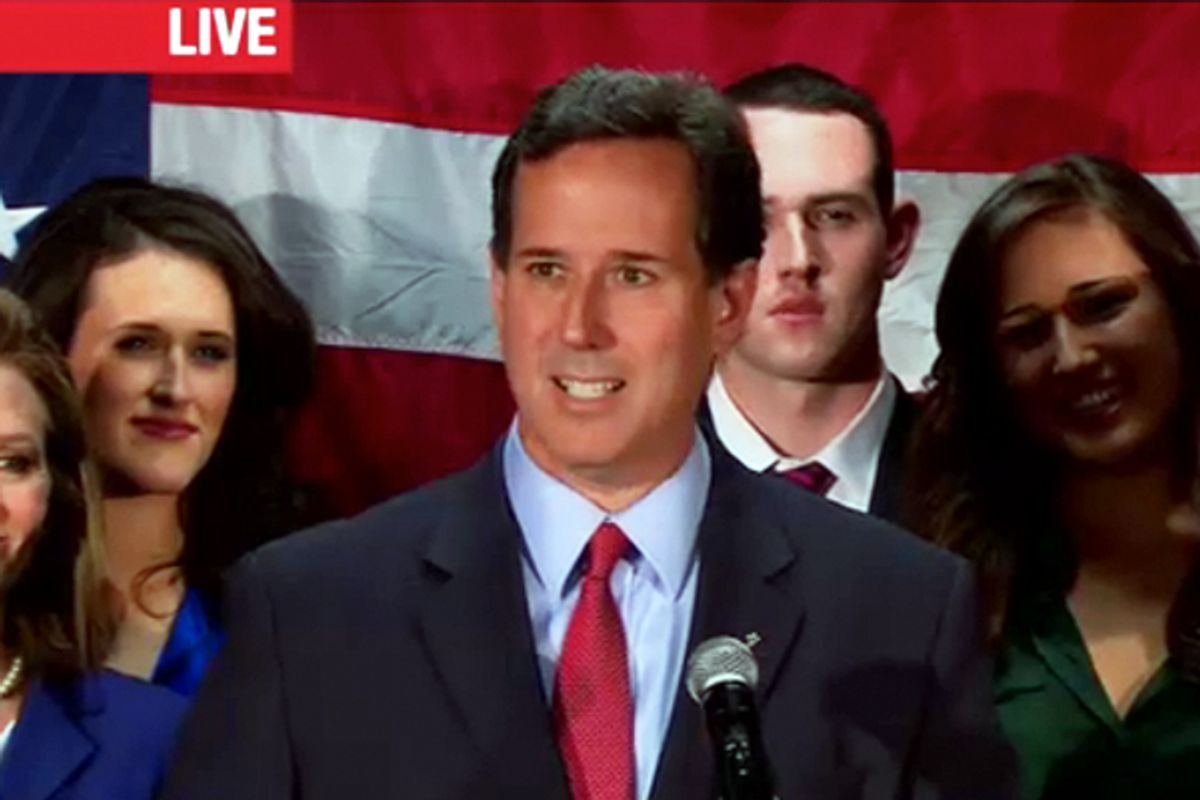

Rick Santorum finally admitted defeat and ended his presidential campaign this afternoon. That he lasted this long and leaves the race with several hundred delegates is a rather amazing feat, considering how futile his efforts seemed until the final days of 2011.

Still, Santorum really isn’t really dropping out voluntarily. The odds of winning the Republican nomination were remote (if that), but the possibility of a bunch more of primary and caucus victories in May and June was very real. In a speech last week, Santorum likened his candidacy to Ronald Reagan’s 1976 primary challenge to Gerald Ford, playing up the fact that Reagan only began winning states in big numbers late in the primary season. The implication seemed clear: Like Reagan, he hoped to make a late statement that would carry over to the next campaign.

But then Pennsylvania got in the way – again.

It’s doubtful that any presidential candidate has ever been as thoroughly undercut by his home state as Rick Santorum has. When he set out to run for the GOP nomination, he was just a few years removed from a landslide Senate reelection loss in the Keystone State. The perception that he was a “loser” colored the media and political world’s perception of his candidacy. Even though he met their various ideological litmus tests and was a natural fit for the “non-Romney” role in the GOP race, Santorum couldn’t get his own party to take him seriously for almost all of '11.

That he ultimately did gain traction stands as a fluke for the ages; conservatives first cycled through Herman Cain, Michele Bachmann, Rick Perry, Cain again and Newt Gingrich before finally giving Santorum a look on the eve of the Iowa caucuses. And because of the late date, Santorum was spectacularly ill-equipped to capitalize on his sudden momentum. Missed ballots, empty delegate slates, cash shortages, and thin staffing haunted him throughout the winter and spring, putting him in a deeper delegate hole than he should have been in.

Despite all of this, Santorum still managed to nab 11 primaries and caucuses, and came within a few points of scoring wins in Michigan and Ohio that just might have, against all odds, turned the GOP race in his favor. And even as the inevitability of a Romney nomination took hold, Santorum posted a crushing victory in Louisiana a few weeks back and still came within a few points of winning Wisconsin last week. Given the demographic divide that has driven the GOP race, he had a chance to defeat Romney in as many as nine May and June contests. That wouldn’t have given him the nomination, but it could have cemented him as the consensus conservative candidate for 2016.

To get to May and June, though, Santorum first had to make it through this month and its marquee contest: the April 24 primary in his Pennsylvania. Victory was certainly possible; the most recent polls showed him running a few points behind Romney, and who knows what a concerted appeal to voters’ home state pride might have yielded Santorum? But the risk was profound. Favorite son candidates almost never lose their home states; the last one to do so was Jerry Brown, who lost the June 1992 California primary and then spent the next six years in the political wilderness. For Santorum, a Pennsylvania loss to Romney might have washed away all the progress he’s made these past few months and left him with the same “loser” reputation that haunted him before.

And so the Santorum 2012 campaign comes to an end. By dropping out now, he spares himself a possibly humiliating defeat and also spares Romney a string of potentially embarrassing losses in May and June. Now Romney can set his sights on the election campaign against Barack Obama, while Santorum can set his on 2016.

Shares