While some people think doctors see themselves as gods, oblivious to their mistakes, the behind-the-scenes reality tends to be quite different. In regular meetings called "morbidity and mortality" (or M&M, for short), doctors close the doors and candidly discuss their mistakes and try to learn from them. The meetings can be full of ruthless -- and helpful -- self-flagellation.

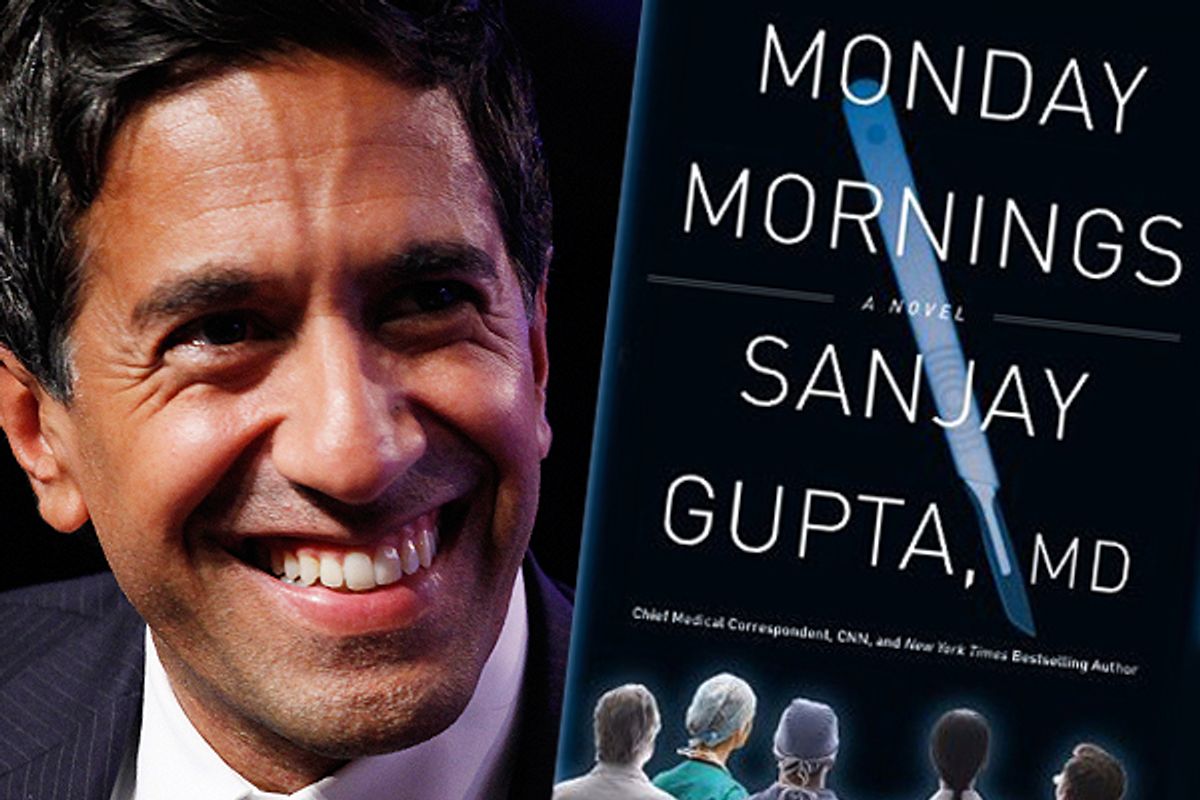

Most people don't know they even take place. Now, "Monday Mornings," a novel by Sanjay Gupta -- CNN's chief medical correspondent and a practicing neurosurgeon at Atlanta's Emory University -- lifts the veil on these gatherings.

While driving one of his three daughters to school last week, Gupta, 42, talked to Salon about his bestselling first novel, how doctors can do better, and the controversial ethics of being both journalist and physician.

What made you decide to leap into fiction?

It was an evolution. Originally, I wanted to write a nonfiction book about my specific experiences as a resident. I always took very diligent notes, and when I pulled them out, it really reminded me about that time. Then I learned that the whole idea that a meeting like M&M even exists was surprising to a lot of people. I had assumed that most people knew that doctors and surgeons got together regularly to discuss their mistakes. It turns out that most people didn’t know that, even ones who work in health care. This was interesting in and of itself. So I wanted to show people that this existed and that it can be one of the most indelible experiences that somebody can ever have. But to do that, it would need to be fiction, so it could be more unrestricted and have some creative power.

What’s the message of the book for doctors and their patients?

I think the biggest point was to expose people to M&M. When a mistake happens, or an unexpected outcome, oftentimes the immediate thought is “That’s a bad doctor." They may even think “That’s a bad human being.” Most of the time that’s not true, and often doctors beat themselves up, to the point where I’ve seen some of them disengage. They no longer feel they’re up to it. They couldn’t stand the fact that someone got hurt because of something they did. So I wanted to tell a story about how people react to a mistake in medicine, and then to show the accountability that doctors hold for each other is sometimes far worse than any other punitive system. It doesn’t take the place of malpractice or administrative sanctions. This is doctors on doctors -- and sometimes that has a much greater impact. It’s a pretty unique thing -- the idea that you close the doors and be candid. It’s worth asking whether there’s a role for that kind of meeting in other places in our society as well.

Are we in medicine good at learning from our mistakes?

In 1999, because of the Institute of Medicine Report, people started paying more attention to medical errors. It’s not a great study, and even the way they define mistakes is different [from how others in the field] define mistakes. Still, there’s a problem, and over the past decade or so we have focused on this, and some of the things people have done have been effective at trying to curb mistakes. Yet if you look at the number, there’s hardly any evidence that mistakes have gone down.

So learning from our mistakes requires a more immediate sharing of the lessons. There’s also the cultural change for any new thing that needs to be done. These things need to come from within the medical community as opposed to being mandated. How do you get a significant cultural change and get everyone to buy into it? One place I saw cultural change happen lightning-fast was through the M&M meetings. It was so indelible and vivid, it just became the way we did things.

During the book's first M&M meeting, the chairman of your fictional team of surgeons, Dr. Harding Hooten, makes a statement about missing the basics in medicine. Do you think doctors in this country, because of the cushion of medical technology, have lost sight of getting the fundamental medical history and giving a complete physical?

No question. We overtreat. The irony is that we do this in part to prevent errors -- and as a result we probably make more errors. As I was writing the book, I read Abraham Verghese’s essay in the New York Times. I attempted to incorporate some of that into Hooten’s dialogue.

Can we go back? Is it too late to regain that appreciation and rely on a conversation with and an exam from your physician?

It’s difficult to go back. I think we can mitigate some of the increase in the use of technology. Some of that was part of the discussions around health care reform. I also think that our tolerance for risk in medicine is different from anything else we do. I hate to be trite, but if a plane crashing every day would equal the same number of people who die each year from medical errors -- we haven’t done a good job of explaining risks and benefits very well. Even informed consent is almost like a hat tip; people do it because they have to, not because they really sit down and really have a conversation about the risks.

What about the patient’s side of the equation? When you see the story of the face transplant or the former vice president getting a heart transplant, you’re left with the view that in American medicine, all things are possible. Is there a way we can communicate better what it is what we can and cannot do?

Yes. It’s hard because people want those stories. It’s a tough balance, and we have to be very careful in our reporting to present the risks of things. I think people tend to focus on costs, but they don’t talk as much about risk.

When you were in Haiti in 2010 covering the earthquake, some people criticized you for becoming part of the story when, with cameras rolling, you began caring for patients at an abandoned medical camp. What’s your view of balancing journalistic objectivity with your commitment as a physician?

It’s a little bit artificial to say journalistic objectivity and helping people when you can are somehow at odds with one another. I’m not in way trying to demean journalistic objectivity. But whether or not you’re a physician, if you can help someone as opposed to just sitting there, I think most people from a human standpoint will do that. Anderson [Cooper] for example, was in a situation once where a boy was getting pummeled with rocks. He was right there and grabbed the kid and pulled him out. You would do it. Anybody would do it.

It’s worth pointing out that so much of the time I was in Haiti, for example, I was going to general hospitals and doing things. It wasn’t stuff for the cameras. There was just a tremendous need, as journalists get into these situations so quickly. Many times we are the first ones there before anybody else. In Haiti we were there within 12 hours of the earthquake because we have such an infrastructure built into the work that we do. In Iraq, I was embedded with Navy doctors; I was reporting on them and what was happening. And then I was asked to operate because there were no neurosurgeons there. I took some criticism for that, and that was early on in my career, and I was a bit befuddled by it. Having trained as a doctor, why would anybody think that I wouldn’t do it? But when I came back and had lots of conversations with lots of other people in the journalism community, they raised the question of whether I can be objective. I think it was a worthy discussion to have, but as a general rule, I don’t think putting on a press badge means parting with your humanity. I’m pretty comfortable that as a journalist-physician, I am a physician first.

How do you keep a balance between your duties as a doctor and your duties as a journalist?

It’s pretty busy. I like to make rounds early, around 5 to 5:30 a.m., so I can come back and take the girls to school. I find that the car rides are the only times where you get one-on-one time and get to talk. When you have three kids, the house is active. The medical stuff, the work, has a pretty defined schedule. Every Monday and every other Friday I operate. In total, it’s about 2.5 days a week of work. Straddling two fields, I have a view of both. I know medicine’s changed a lot. But when I wake up in the morning, when I’m in the operating room, there’s such a clear sense of purpose. It’s very hard to replicate that in anything else I do or anywhere else in society. I love that part of my life.

Shares