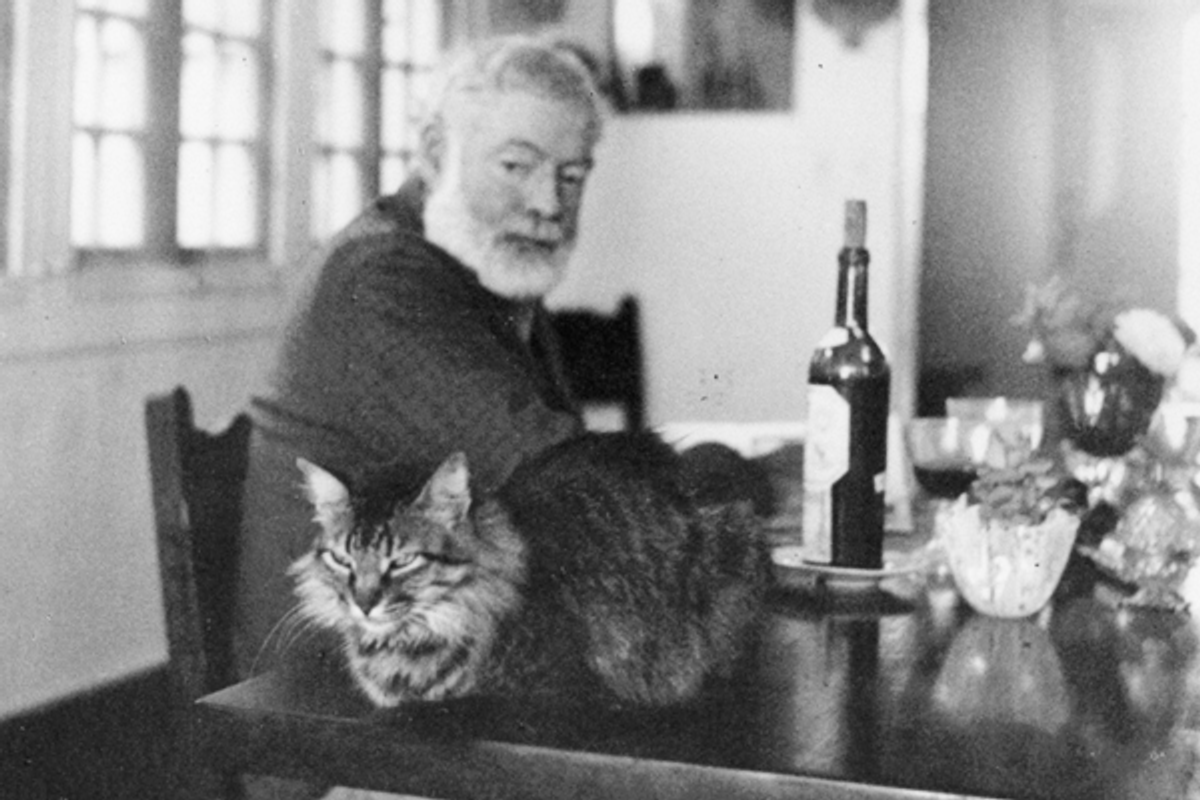

Here’s Ernest Hemingway, dead drunk on a stool in Cuba with his face on his hand and his hand on an ever-present mojito. He's the tormented writer, hard at work at the daily scrubbing of his sins. Like the Hard-Drinking Writer, we've come to expect certain personality types to have certain habits: The Morose Musician with Keith Richards' appetite for heroin; the Insecure Starlet with Marilyn's taste for pills; the Monomaniacal Money Manager with a nose for cocaine. They are generalizations that have been imprinted by generations of popular culture. But the types don't necessarily line up.

The logic of associating personalities with specific drugs seems natural. A German-British psychologist named Hans Eysenck spent the mid-20th century turning the eye of the scientific community from Freud’s behavior-based theories to individualized psychology—pioneering the science of personality. He considered this pursuit of matching personalities with drugs a pet project.

The logic of associating personalities with specific drugs seems natural. A German-British psychologist named Hans Eysenck spent the mid-20th century turning the eye of the scientific community from Freud’s behavior-based theories to individualized psychology—pioneering the science of personality. He considered this pursuit of matching personalities with drugs a pet project.

Eynsenck believed the ways people are inclined to think aren’t always the ways that make us feel best. And because drugs are the easiest way to modify temperament, it’s only natural for us to seek out those substances that keep us on an even keel. For instance, he thought that introverts, whose brains are always chewing at problems, should crave depressants to quiet the incessant mental chatter. Extroverts, easily bored, should chase the rush of stimulants.

His theory condensed individualized drug cravings into an easy, logical framework—but he was wrong. Or at least, he vastly oversimplified the concepts of both “personality” and “drugs.” Worse, his theory wasn’t borne out by research. Study after study showed both introverts and extroverts drinking alcohol (a depressant) to excess. And extroverts didn’t limit themselves to uppers; it seemed they would reach for all kinds of substances.

So where does that leave us? Well, scientists kept trying to tie the two nebulous concepts together. Over the years, as new methods of personality screening emerged, researchers continued to distribute questionnaires to groups of drug addicts. One major breakthrough came when four sets of psychologists independently realized in the 1980s and 1990s that a person’s personality traits—tendencies that are partially genetic and tend to last throughout life—can be pretty reliably described using five factors.

Introversion and extroversion weren’t enough, they thought. We should also consider openness to new experiences (think Bear Grylls), conscientiousness (Haruki Marukami), agreeableness (Mother Theresa) and neuroticism (Woody Allen) when trying to understand why people act the way they do. Thus armed, personality psychologists began fitting the various personality traits they had come up with over the years into what came to be called the “Big Five.” And lo, with a more accurate representation of traits, a connection between personality and drug use began to emerge.

People who tested high on neuroticism (indicating that they tend to be impulsive, emotionally unstable and anxious), low on conscientiousness (tending to be disorganized, unambitious and lazy), and low on agreeableness (tending to be uncooperative, unhelpful or misanthropic), were more likely to have problems with alcohol or drugs than people whose scores were closer to the middle, or reversed. Perhaps more interestingly to the question of whether personality traits led their owners to cocaine over alcohol, or marijuana over mushrooms, higher scores for each risky trait were linked to higher likelihood of using "hard" drugs like heroin, amphetamines or crack.

“There is some evidence that the more ‘bad’ traits you have, the harder the drugs you’re going to use,” says Michigan State Department of Psychology professor Chris Hopwood. “So super, super-impulsive, sensation-seeking, neurotic people might be inclined to use something like heroin, for example, whereas if you’re a little bit less impulsive or have more anxiety about things maybe you wouldn’t. Maybe you would use other drugs but you would be too afraid to use heroin.”

Not all the personality factors that appear in people with drug problems are negative, however:

Sensation-seeking—a facet of openness to experience that’s common among extreme sports athletes, explorers, philanderers and roller coaster-enthusiasts—is almost always associated with drug abuse, but doesn’t necessarily scale with using harder drugs. Marijuana users, for instance, have been shown to be high in sensation-seeking, with closer-to-average levels of neuroticism.

Sensation-seeking seems to be about 60 percent heritable—meaning about 60 percent of the trait comes from your genes—and appears to be related to the brain’s dopamine reward system, the same system that makes most drugs of abuse pleasurable. Sensation-seeking may even be related to where you live, through interactions with neighbors—or, in the case of, say, New York City, through self-selection. A study by Jason Rentfrow, Sam Gosling and Jeff Potter that was analyzed by Richard Florida on the Atlantic’s Atlantic Cities blog showed that Openness to Experience scaled with drug use when compared within states. And which states had the highest levels of both illicit drug use and openness? Colorado, Vermont, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, Massachusetts, New York and California.

Given the personality characteristics that seemed to split “hard” versus “soft” drugs, scientists began to wonder if—even if they couldn’t predict who would take uppers over downers—there was a way to predict who would become an alcoholic and who would abuse illegal drugs. The studies showed some remarkable similarities: One study conducted among veterans suggested that all addicts share interpersonal styles that tend toward loner, rebel and pessimist stereotypes, for example, which surprised no one who has ever seen "Leaving Las Vegas." But there did appear to be a little something extra that could push a person into hard drug addiction.

People who use illicit drugs often have been shown to have higher rates of both extroversion and susceptibility to boredom, which may drive them into more situations where drugs appear, or simply make them more likely to crave new subjective experiences. And those who are particularly susceptible to boredom have been shown to use opiates more often.

But this is where the studies break down. Most research on the topic of how personality relates to drugs of choice is conducted among people who already have drugs of choice—addicts. And as any addict knows, once you’ve taken a shine to a drug, it can be exceedingly difficult to disentangle the personality factors that came before from the ones that came after. By the time the personality questionnaires are administered, who’s to say what caused the drug use and what the drug use caused?

“It could go either way,” says Hopson. “A person who uses heroin might end up having problems in their life. Perhaps he loses his job, perhaps then he starts stealing things. You could easily tell a story that goes, the heroin started first and then the person started doing all kinds of mean antisocial things. Or you could tell a story that says that the person was sort of a ‘bad’ person, if you’ll forgive the language, and one of the bad things they did was use heroin.”

There are also direct effects of drugs that scientists have to consider. Crack and cocaine abusers, for example, have shown personality traits related to the symptom of paranoia in certain studies, as well as depression and impulsivity and a trait terrifyingly called “psychoticism.” Because long-term crack or cocaine use can cause many of these effects, however, it’s unlikely that those traits cause people to take up stimulants. Rather, it appears that long-term crack or cocaine use might be able to alter the expression of certain traits to create a “stimulant user profile.”

Regardless of the qualms of scientists, however, quiz websites and message boards hoping to connect personality to a particular drug have popped up all over the Internet. Many focus on Myers-Briggs personality types (ENFP, ISTJ, etc.), which are commonly used by career counselors to assess how people prefer to perceive and organize information. Others skip the science altogether, selecting a drug you’re likely to use based on the clothes you wear, the events you attend, where you live, and your perceived flaws.

Will science ever reach that degree of accuracy—explaining just what it is that seems to make neurotic writers more likely to drink than use heroin? It’s certainly possible, says Hopson. “One way to think about personality is in terms of traits, which are stable and heritable. But you can also think about personality dynamics, like how do I react if you insult me, for example. That’s sort of my guess is that which drugs you use depend on the more complicated personality dynamics.”

Assuming you’ve got the traits that push you toward drug use in the first place, what else might lead you to one substance over another? Hopson says factors that play a role include what your parents use, what your friends use, and even simply what’s available where you live. Which perhaps explains Hemingway’s situation better than we could have expected: there sure was a lot of rum in Cuba.

Shares